Tag: Wolverton

Sometimes a tale’s ending is so ghastly, we might be tempted to change it in the retelling. And, in the process we might introduce a few improvements to the rest of the tale. Our written history is replete with such improvements, and the story of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks hasn’t escaped embellishment. This is a four-part series that explores a small portion of the embellished lore associated with the creation of Sequoia National Park, exposing little-known aspects perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. In this first part of the series, we meet a ghastly end and reminisce about a legendary man whose life concluded just as the Park’s began.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 1 October 2019, 3RNews

It was pitch black the night of May 23, 1903, and William Trauger was falling down a forty-foot mine shaft.

Will was properly drunk. Nevertheless, he was also forty-two years old and had a full life to flash before his eyes, assuming he sobered enough on the way down:

Bleary visions of the preceding hours at Phillip’s Place, a fine drinking establishment that he and his partner Will Kenna frequented when they weren’t seeking their fortunes in gold. A decade of mining in Mineral King for his friend Arthur Crowley. The time they caught some trout and carried them in coffee cans up to the lowest Mineral Lake. His home and apple orchard by the old wooden bridge at the base of the Mineral King Road.

And Wolverton.

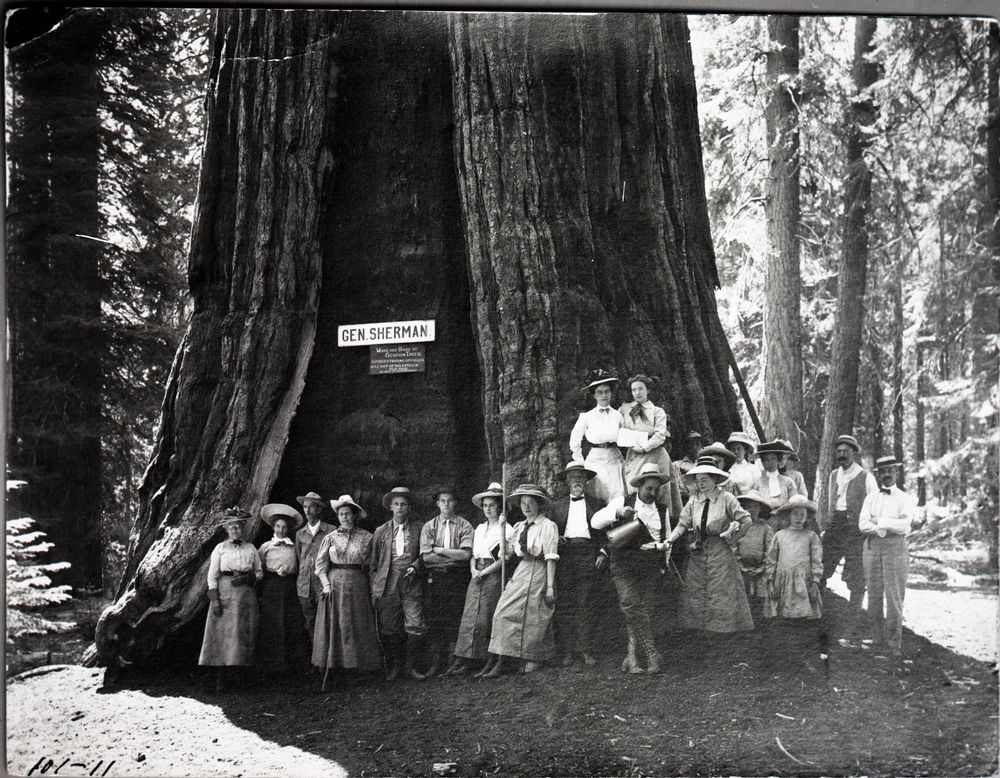

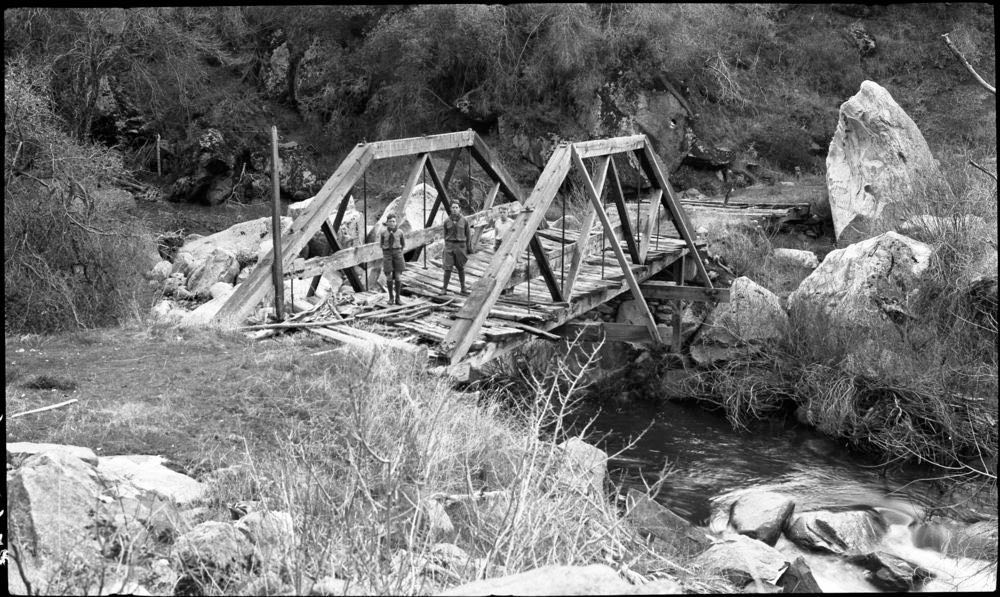

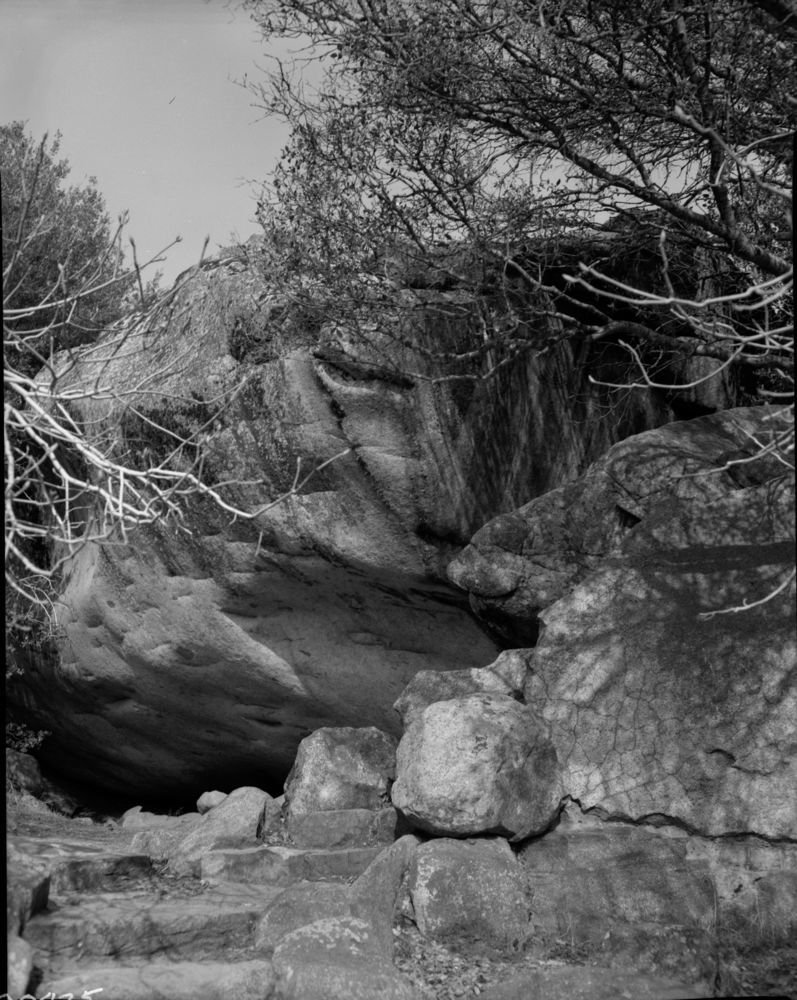

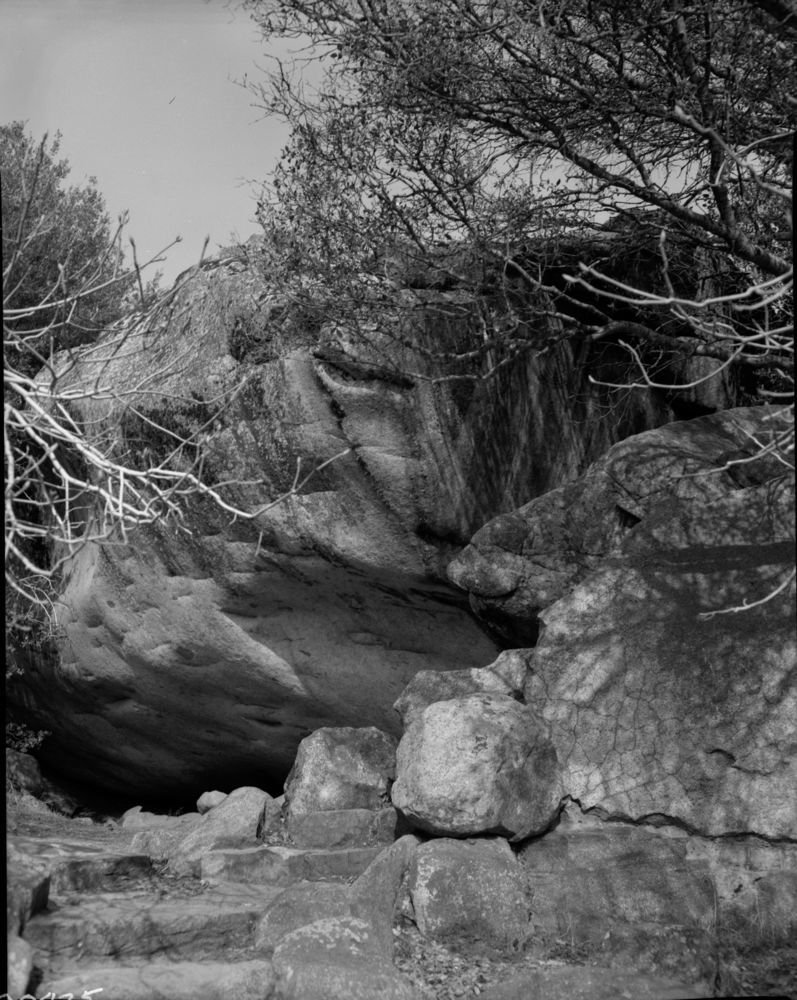

The name Wolverton is indelibly associated with Sequoia National Park. There is Wolverton Meadow, of course, a favorite snow play area in the winter and a popular trailhead in all seasons. Visitors can also find Wolverton’s name while exploring the history of General Sherman, the world’s largest tree, and Hospital Rock, a granite shelter featuring Potwisha Monache pictographs. Although there are variations, Wolverton’s story appears well known.

Popular accounts inform us that James Wolverton was a cowboy, fur trapper, and naturalist who arrived in the Sequoia area in 1874. He developed a close friendship with the area’s first Euro-American settler Hale Dixon Tharp and built a small cabin in what is now known as Wolverton Meadow. He discovered the largest sequoia and named it the General Sherman on August 7, 1879. Wolverton had earned that honor by serving as lieutenant in the 9th Indiana Cavalry under General William Tecumseh Sherman in the Civil War.

According to local lore, Wolverton eventually homesteaded 160 acres on the Mineral King Road. There he raised stock and built a home at Wolverton Point, where the helipad is now located. In 1893, however, he was working for his friend Hale Tharp as a lookout near Hospital Rock when he fell ill. Members of the local Potwisha Monache tribe took care of him until Tharp found him. Tharp first transported Wolverton twenty-five miles downriver to his home near Horse Creek, and then back upriver to the Last Chance Ranch halfway up the Mineral King Road. There, Will Trauger’s father and adoptive mother, Mary, lived. Mary, who was known as the angel of Mineral King, tended Wolverton until his death.

For unknown reasons, Wolverton had asked to be laid to rest by the wooden bridge that crossed the river near the base of the Mineral King Road. Captain “Galloping Jim” James Parker of the 4th Cavalry was acting superintendent of newly formed Sequoia and General Grant national parks. He attended the service and gave Wolverton the military burial honors befitting a lieutenant in General Sherman’s army.

A wooden marker was placed at the head of Wolverton’s grave. At some point over the next few decades it was consumed by a brush fire, and the location of his final resting place was forgotten. Only his name and his story remained.

As we will see, however, there are a few issues with this narrative. Foremost among them is that James Wolverton, as such, never existed.

As for Will Trauger, he hit the bottom of the forty-foot shaft after only 1.577 seconds. At the time of impact, he was moving at about 34.59 miles per hour.

And the saga continues: James Wolverton and the Ghastly End pt. 2

This is the second installment of a four-part series that explores a small portion of the embellished lore associated with the creation of Sequoia National Park, exposing little-known aspects perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. In Part 1, we met Will Trauger, who was plummeting down a mineshaft, and James Wolverton, a legendary man whose life concluded just as the Park’s began. This week, we join some Boy Scouts on a search for James Wolverton’s grave.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 7 October 2019, 3RNews

The rattlesnakes were still dormant on the first day of March in 1936. Seven boys were walking on the hillside above the East Fork of the Kaweah River. They rustled through the stalks of last year’s grasses still towering above new green growth, and they inhaled the overpowering smell of buckthorn blossoms. The boys were seeking a spot on the ground under which the bones of a hero lay.

They were seeking the grave of Lieutenant James Wolverton. With the Second World War looming overseas, honoring the resting place of the local Civil War icon made for a meaningful outing. The boys were members of Troop 23 led by Lloyd Fletcher, a local landscape architect whose work is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

The nature and timing of the boys’ adventure was no accident. The troop was sponsored by the Big Tree American Legion Post – the same big tree purportedly named General Sherman by James Wolverton. Frank Been, Sequoia National Park’s first full-time ranger-naturalist led the outing. At the same time, Sequoia National Park was preparing to host a Boy Scout camp at Wolverton Meadow. Well-publicized resurrection of Wolverton as a symbolic hero made sense.

The story of James Wolverton and his naming of the General Sherman tree emerged as early as 1914 in newspaper articles promoting Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. By 1935, Wolverton’s tale had fully evolved, and numerous newspapers published large front-page articles featuring the hero. With his journalistic exhumation, Wolverton’s reputation grew. Wolverton had now become an acquaintance of John Muir, and he was patrolling the Park at the time of his death. Most articles ended by wondering why James Wolverton chose to be buried in an isolated grave.

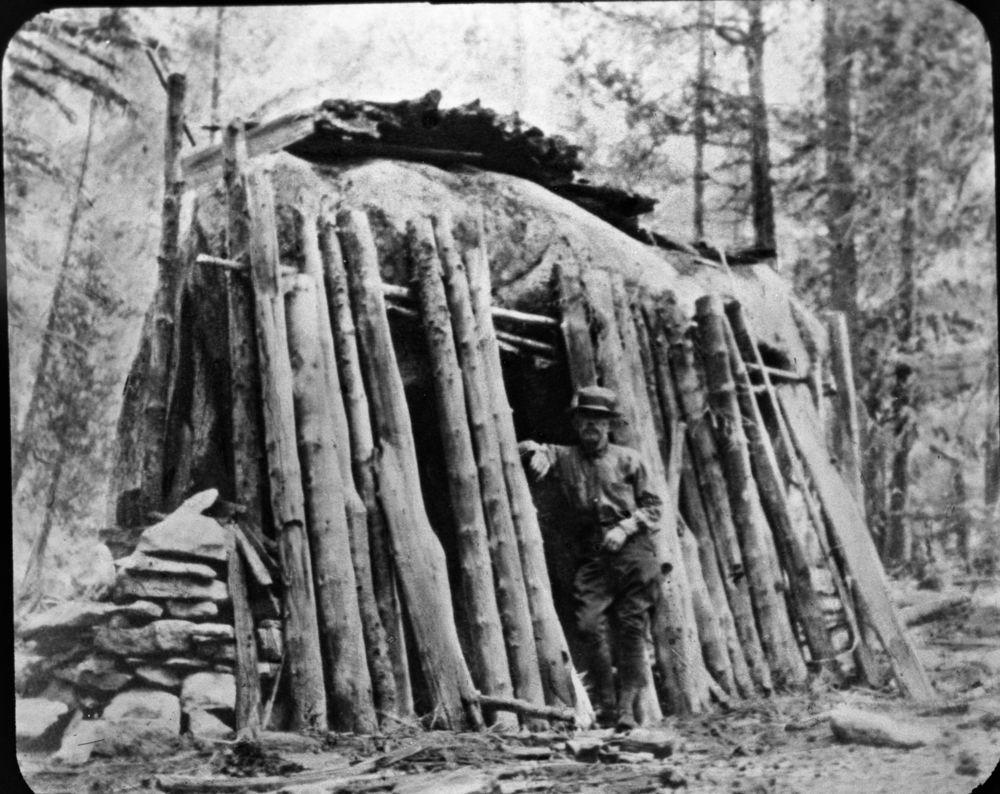

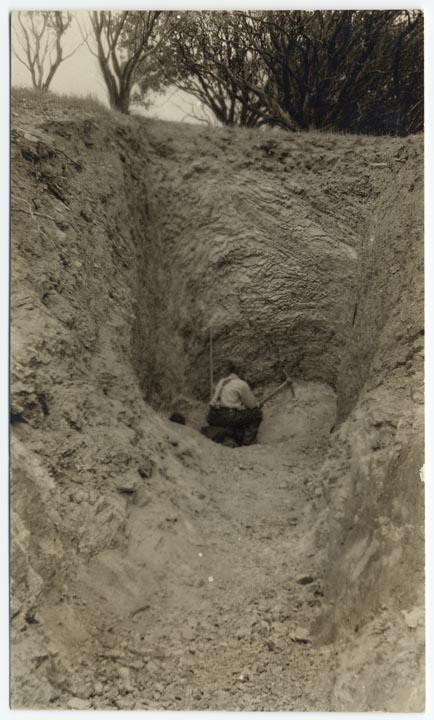

According to local lore, Wolverton’s grave was near a wooden bridge built in 1879 to carry miners and supplies to the Mineral King mines and silver ore back down. There, in in October 1893, Wolverton supposedly received a dignified burial with the military honors suitable for a Civil War lieutenant who had served under General Sherman. In 1936, the bridge was still standing, but the road was no longer in use. Fire had swept through, consuming any grave markers in its path, and new vegetation had obscured any telltale mound or depression. James Wolverton’s gravesite needed rediscovery.

Jim Barton, 95, of Three Rivers was eleven years old on that day. He remembers walking the abandoned Mineral King Road down to the East Fork of the Kaweah River and the rickety wooden bridge that crossed it. According to contemporary newspaper reports, the boys found a site distinguished by a large moss-covered bolder. Two weeks later, they returned with new wooden head and foot markers and built a trail to the site.

Given the passage of more than four decades and at least one brush fire, however, is it certain the boys found the exact location of the grave? How would the troop definitively recognize the gravesite? When reminiscing in 2002, Jim Barton expressed some uncertainty.

“I don’t think we found it,” he noted before reminding his listeners of the effect time wields on memories.

Compounding the doubt is another mystery. There are no census, voting, or property records for a James Wolverton in Tulare County between 1874 and 1893.

Regardless, two things are now nearly certain. Forty-three years before young Jim Barton sought the grave, and a decade before plummeting down a forty-foot shaft, Will Trauger’s boots compressed the soil under the Boy Scouts’ feet. And somewhere in the vicinity lies a six-foot skeleton exhibiting the ravages of what could well have been venereal disease.

In the next installment, we follow the path of a man named Joel Rivers Woolverton to his ghastly end.

This the third installment of a four-part series that explores a small portion of the embellished lore associated with the creation of Sequoia National Park, exposing little-known aspects perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. In previous segments, we met Will Trauger who was tumbling down a mineshaft (Part 1), the legend that’s James Wolverton, and a group of Three Rivers Boy Scouts searching for Wolverton’s grave (Part 2). In this third part of the series, we meet Joel Rivers Woolverton at his ghastly end.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 14 October 2019, 3RNews

Before we return to Will Trauger at the bottom of a forty-foot mine shaft, let’s step back to a time when Will owned the property where Three Rivers Boy Scouts were to seek James Wolverton’s gravesite in 1936. It’s the last week in March 1893, and Joel Rivers Woolverton is lying helpless on the ground at Hospital Rock, about five miles northeast of Will’s place.

Joel wasn’t the first Euro-American to lie there, according to Walter Fry, the first civilian superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. In 1860, John Swanson and Hale Tharp, who claimed to be the first Euro-American in the area, were exploring when Swanson injured his leg. They sheltered under Hospital Rock for three days while the Potwisha Monache tended Swanson’s wounds with a poultice of jimsonweed leaves and bear fat.

Joel also wasn’t the first to suffer there alone. In 1873, a hunter and trapper named Alfred Everton was shot in the thigh by one of his own guns. He had stretched a string across a bear trail and attached the string to the gun’s trigger. He meant to shoot a bear with it, but accidentally brushed the line himself. His hunting partner carried him to Hospital Rock where Everton waited alone until his partner returned with help three days later.

Now Joel was there, alone, immobile, dying of an illness that prominently featured an abscessed groin. In other words, it is quite possible he was suffering the final stages of a sexually transmitted disease.

How did he end up at this point?

Joel was born in about 1832 in the farming country of Ossian, New York. His father, Joel Woolverton III, had started producing children at the age of fifteen. Not all survived, but when our Joel was born seventeen years later, he had at least five older siblings at home.

His parents didn’t stop with Joel. By 1840, he had four more siblings, with a fifth on the way.

Perhaps weary of farming, disgruntled with a crowded home, or simply yearning for wealth and adventure, Joel left New York by 1850 to join his older brother Alva and assumed brother Chancy in Ohio. From there, Joel and Chancy traveled overland to the California gold fields. They were mining somewhere in Placer County, California, when they registered to vote in the 1852 presidential election.

Four years later, Chancy was back in Ohio. Joel, however, kept following his dreams of wealth from gold camp to gold camp.

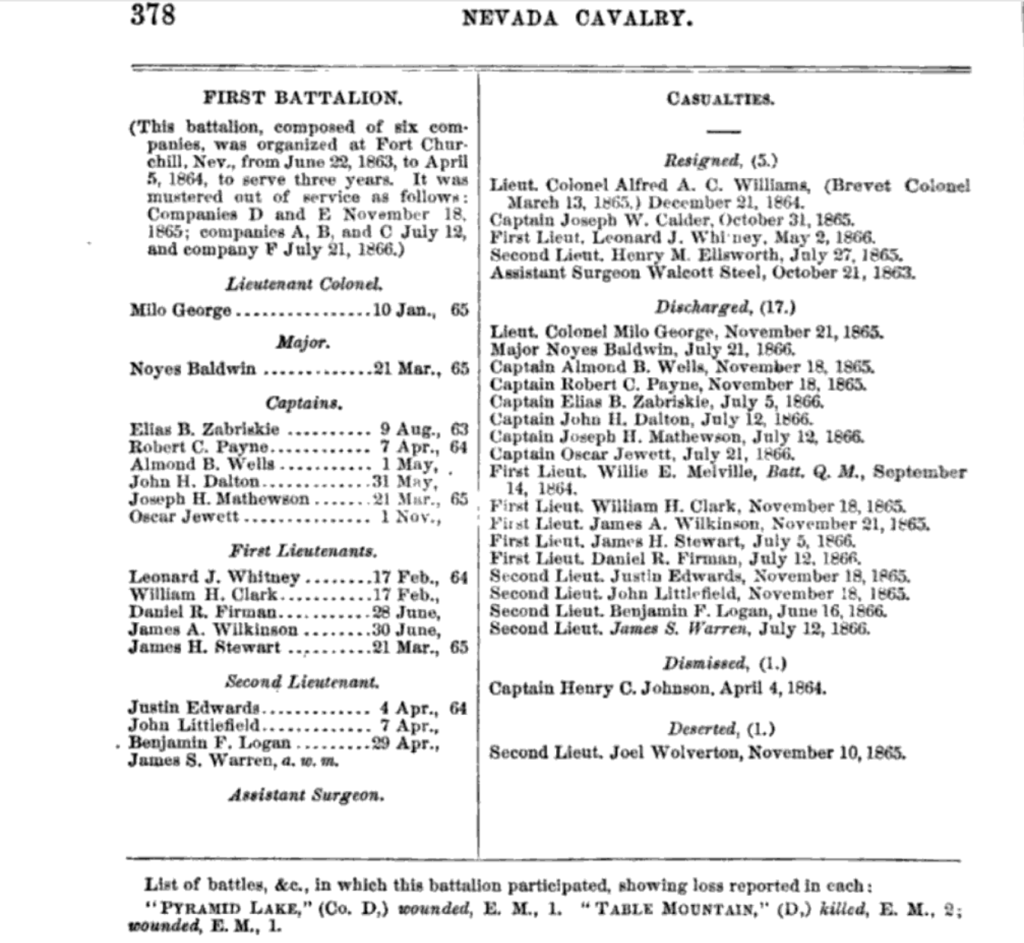

The Civil War found Joel in Gold Hill, Nevada, a district that hosted numerous brothels and saloons. There, Joel joined the Nevada 1st Battalion Cavalry, Company D, on September 3, 1863.

His battalion was formed not to fight the Confederate forces, but to control the remnants of the Southern Paiute tribes in the Nevada Territory. Joel had fair skin, light blond hair, and steel blue eyes. At about six feet in height, he towered over most men of his time. He was consistently present at roll call, and quickly moved up the ranks from private to 2nd lieutenant.

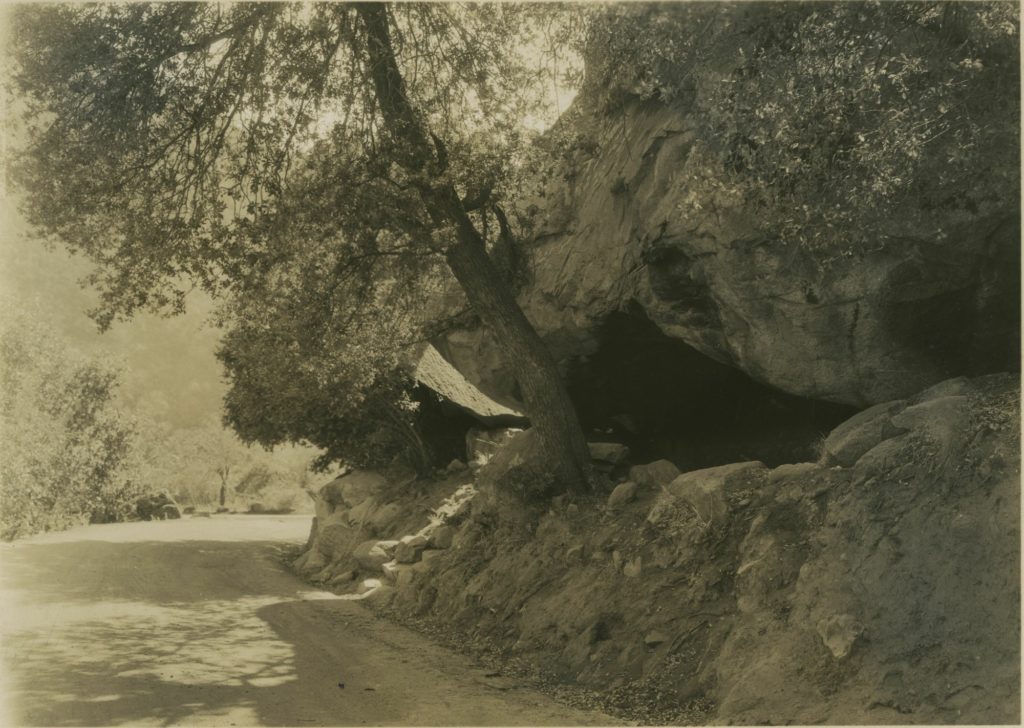

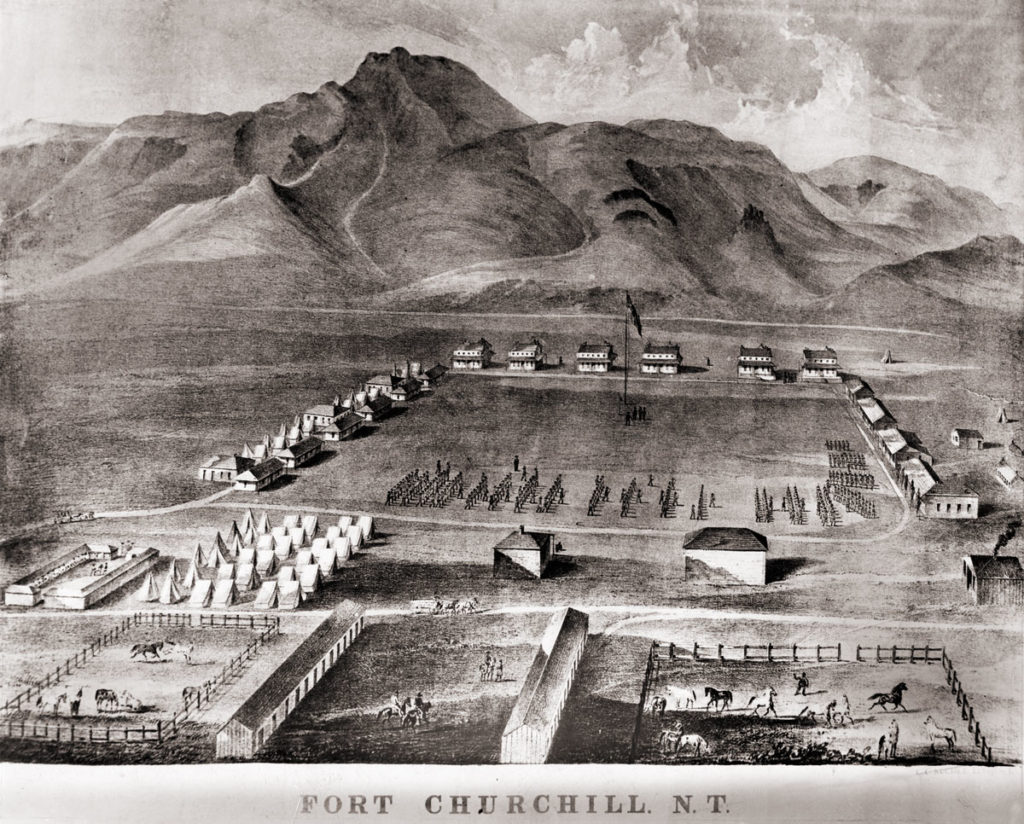

He spent the first year at Camp Nye, where he saw no action but impressed his superiors. The next year, he went to Fort Churchill to attend a court martial and then went to San Francisco to be mustered as a 2nd lieutenant.

After that, he and his company went on some scouting expeditions, but did not detect any hostiles. He was acting post adjutant for a short time. His Civil War service was decidedly uneventful, perhaps even boring.

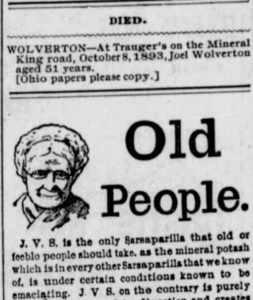

Company D mustered out November 18, 1865. Joel had quit showing up consistently for roll call in September, however, and didn’t show up at all the last week of his service.

As a result, he was the only officer in the 1st Battalion who was declared a deserter. As a deserter, Joel commenced his post-war life without his $50 bounty and land warrant.

After his untimely departure from the Army, Joel seems to have disappeared. He didn’t participate in a census or register to vote, at least not under his given name.

A decade after his desertion, however, Joel resurfaced in the Hueneme District of Ventura County. Named after the Chumash word for “resting place,” the Hueneme District produced an abundance of lima beans and sugar beets. Here, in 1875, Joel registered to vote as a farmer. He had returned to his agricultural roots.

It is uncertain how long Joel resided in Ventura County. A street named Wolverton suggests he may have stayed long enough to make a mark on the land.

Meanwhile, the Nevada government seems to have reconsidered Joel’s record, and officials began to search for him as early as 1869. In 1886, they succeeded in finding him. A certification of service was filed, and on December 8 Joel finally received his $50 bounty.

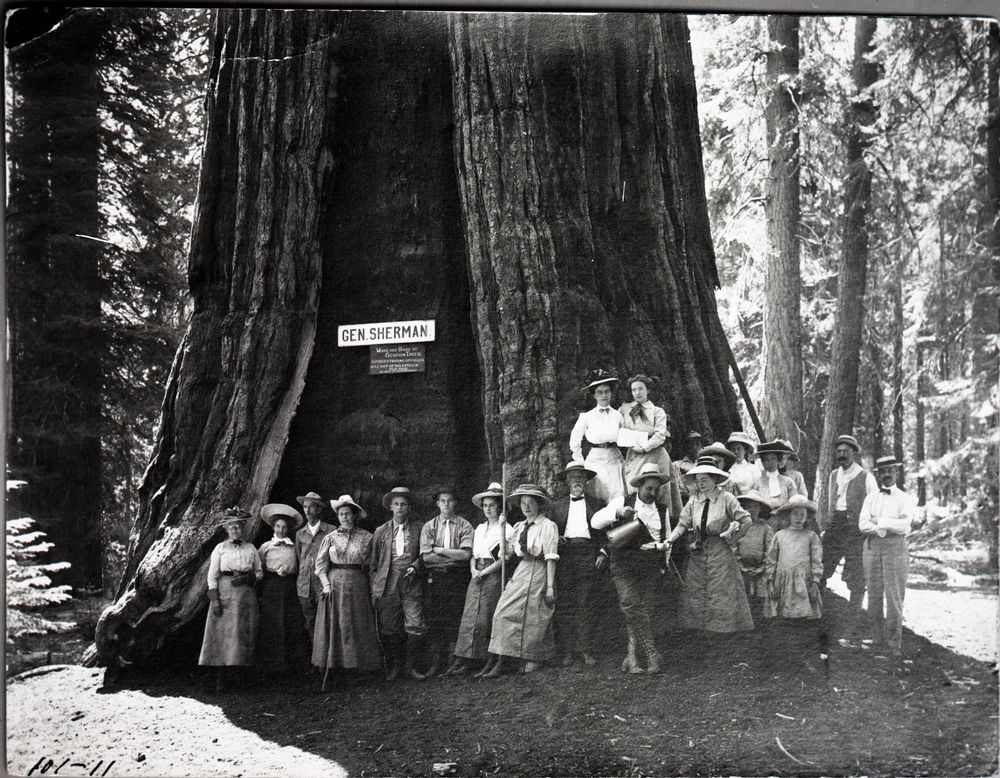

On October 11, 1890, Joel registered to vote in Tulare County as a landless laborer. He was residing in the Kaweah District and may have already taken up residence at Hospital Rock or one of the other abodes that were associated with his name, including Tharp’s Log, Wolverton’s Lean-To, and a cabin in Wolverton Meadow, which was owned by his employer Hale Tharp.

Joel had been troubled by an abscess for some time when he collapsed at Hospital Rock. He could have been lying unable to move for days before Hale Tharp began to miss him.

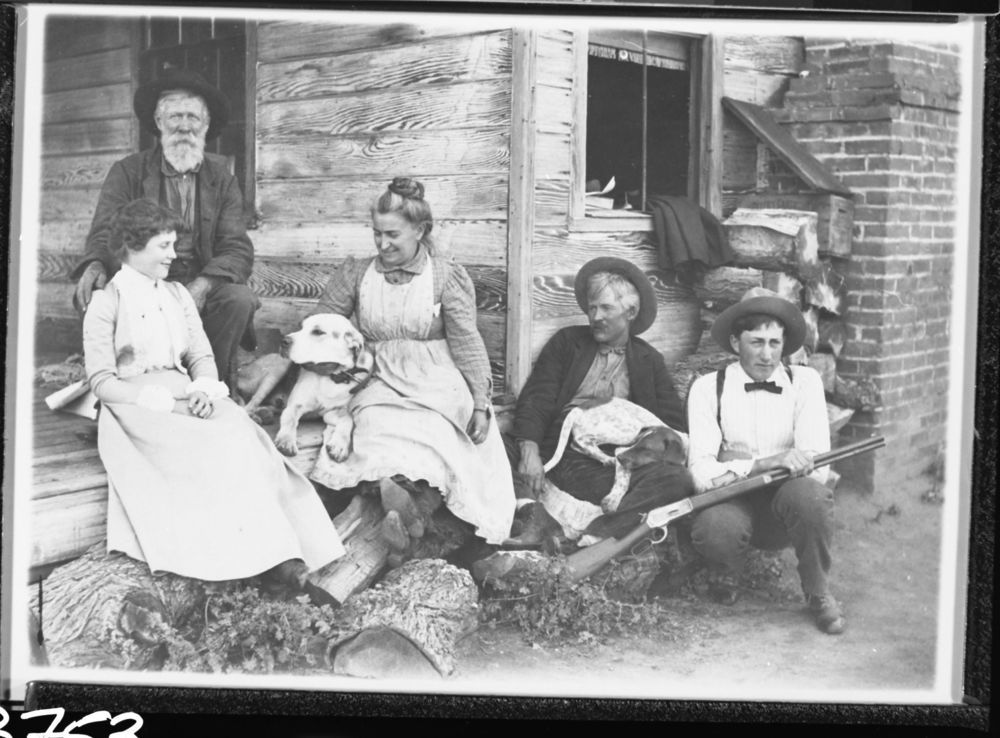

When Tharp found him, it was clear that Joel’s condition was more than he could handle. Tharp went to the nearby homesteads and recruited Will Trauger and two other men to carry Joel 25 miles downriver to his homestead along Horse Creek (present-day Lake Kaweah).

The two-day trip was hazardous due to the heavy spring runoff. The men had to cross the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River holding Joel’s litter above their heads so that the rapids wouldn’t carry him away.

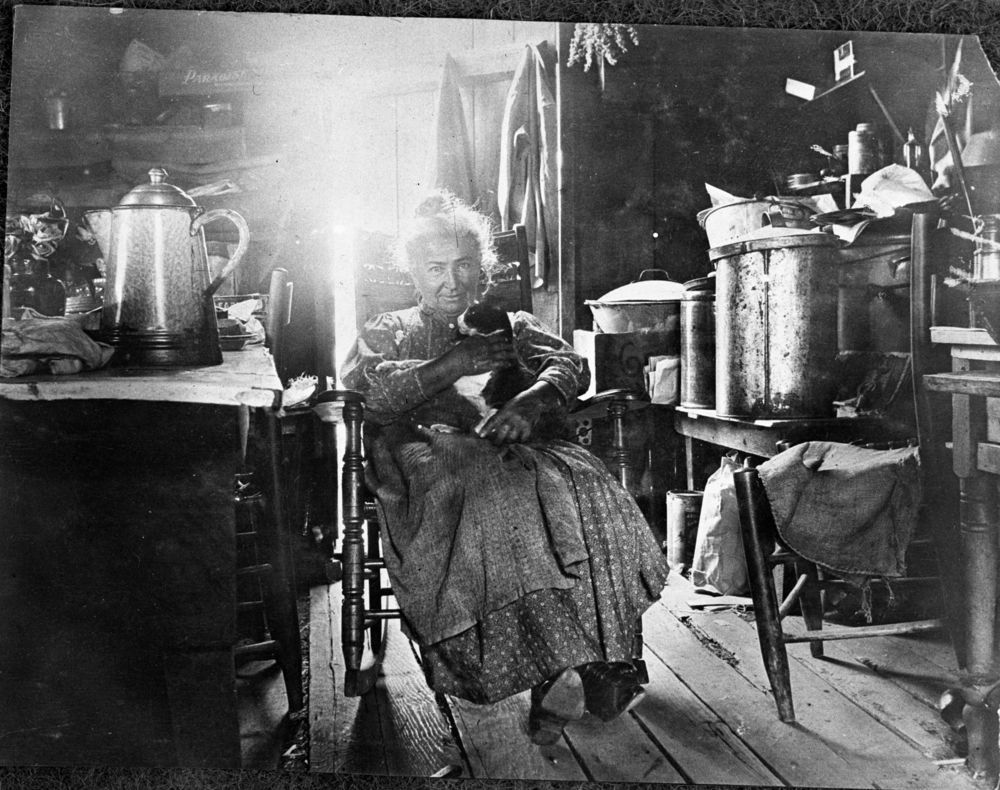

Joel didn’t stay at Tharp’s for long before the men transported him back upriver to Will Trauger’s home, where Will’s adoptive mother Mary Trauger was willing to tend him. Assuming Joel was suffering the final stages of syphilis, he would have had oozing abscesses, dementia, and paralysis. It would have been unpleasant to tend him. Mary had earned her reputation as the “Angel of Mineral King,” however. Additionally, the Tulare County Board of Supervisors voted to pay her an allowance for the six months that Joel remained alive.

Joel died on October 8, 1893. His 61-year life differed substantively from the legend. His name was Joel, not James. Rather than serving under General Sherman, he was a deserter from the 1st Nevada Cavalry.

He was not in Tulare County from 1874 until his death, and there is no evidence that he owned any land in the county. He was a miner and farmer not a cowboy, fur trapper, and naturalist.

He lived his final months in Will Trauger’s house rather than Harry and Mary Trauger’s Last Chance Ranch fourteen miles farther up the Mineral King Road. And, finally, there is no evidence that he named the General Sherman Tree. Indeed, the name was not associated with the tree until 1897.

Joel was buried on Will Trauger’s land, however, as that was where he died. Will’s home was about a mile from the confluence of the East and Main forks of the Kaweah River near where the 1879 Mineral King Road crossed the river on a wooden bridge. Will was almost certainly among those who helped lay Joel to rest under the graying grasses, shrubs, and oaks. There is no evidence that the 4th Cavalry attended, so we will have to provide the sound of Taps ourselves and imagine Will walking away from the grave to find a whiskey bottle. In ten years he was going to collide with the bottom of a deep mineshaft.

Are you “dying” of curiosity about what happened to Will Trauger after he hit the bottom of the shaft? Read the final installment!

Acknowledgments:

This installment drew on the talents and support of multiple people. I am grateful to Savannah Boiano, research partner, naturalist, and adventurer extraordinaire; Bill Tweed, esteemed naturalist and historian, who has been researching the origin of the General Sherman Tree’s moniker; and the staff and volunteers at the Tulare County Library’s Annie Mitchell Room.

Sometimes a tale’s ending is so ghastly, we might be tempted to change it in the retelling. This is the final installment of a four-part series that explores little-known samples of local lore perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. The first installment introduced us to the legend of James Wolverton and to Will Trauger, who was tumbling down a mineshaft. In the second installment we met a group of Three Rivers Boy Scouts searching for Wolverton’s grave. And, in the third installment we followed Joel Rivers Woolverton to his final resting place. In this final part of the series, we face Will’s ghastly end.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 21 October 2019, 3RNews

When we last left Will Trauger, it was the dark night of May 23, 1903, and he had just reached the bottom of a forty-foot mineshaft.

He wasn’t alone. Will Kenna had landed beside him, which wasn’t surprising as the men were seemingly inseparable. They lived together in a small cabin. They mined together when they weren’t drinking, and they drank together when they weren’t mining. They were about to become notorious.

Infamy wasn’t new to Will Trauger. Indeed, he had been born into it.

He started out life in 1859 as William McCoy. His mother, Margaret McCoy, was living with her husband, James, in Congress, Ohio, at the time, as was the presumably ardent Harry Trauger. It didn’t take James long to conclude that Will was not his son, and he filed for divorce from Margaret in 1860 on the grounds of her adulterous relationship with Harry.

Margaret was cast out of her home and denied custody of her two older children. Harry Trauger was no help. He left Ohio for California, abandoning his mercantile and farming businesses for a relatively unsuccessful career as a miner.

Margaret and Will boarded with other families for a time while she developed a career as a women’s hat-maker. By the age of twenty, Will had abandoned her too. He took on the name of Trauger and headed west to find his father.

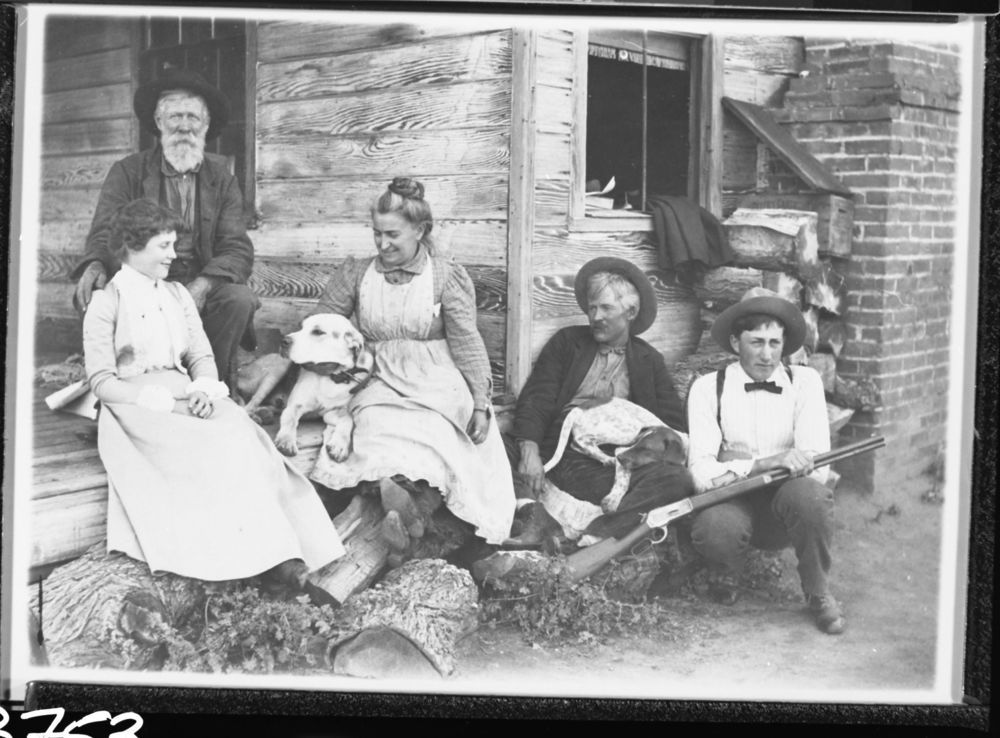

Harry Trauger was at this time living with his indomitable wife Mary on the Last Chance Ranch. He had found a job as supervisor for the duplicitous New England Tunnel and Smelting Company in Mineral King, and was now mining, tending the books as the mining district recorder, and earning a reputation as a drinking man.

When Will arrived, the silver rush in Mineral King was all but over, but he was able to find work as a mining laborer for Arthur Crowley and helped him set up a summer resort in the Mineral King valley. For several years he and Harry also received a contract from the County of Tulare to maintain the Mineral King Road after the road was declared “a disgrace to an enlightened community” in 1893.

Will made a home on the land near the bridge over the East Fork of the Kaweah River, the home where he brought Joel Rivers Woolverton to be tended by his stepmother, and the land where he helped lay Woolverton to rest in 1893.

Will was a tall man at 5 feet, 10½ inches, with blue eyes, fair skin, and hair that had turned prematurely grey. Like his father, Will developed a profound relationship with the bottle.

He partook in intoxicated fistfights and even ended up in jail on one occasion with several of his friends. He was a favorite with the local newspapers, however, due to his exuberance for life.

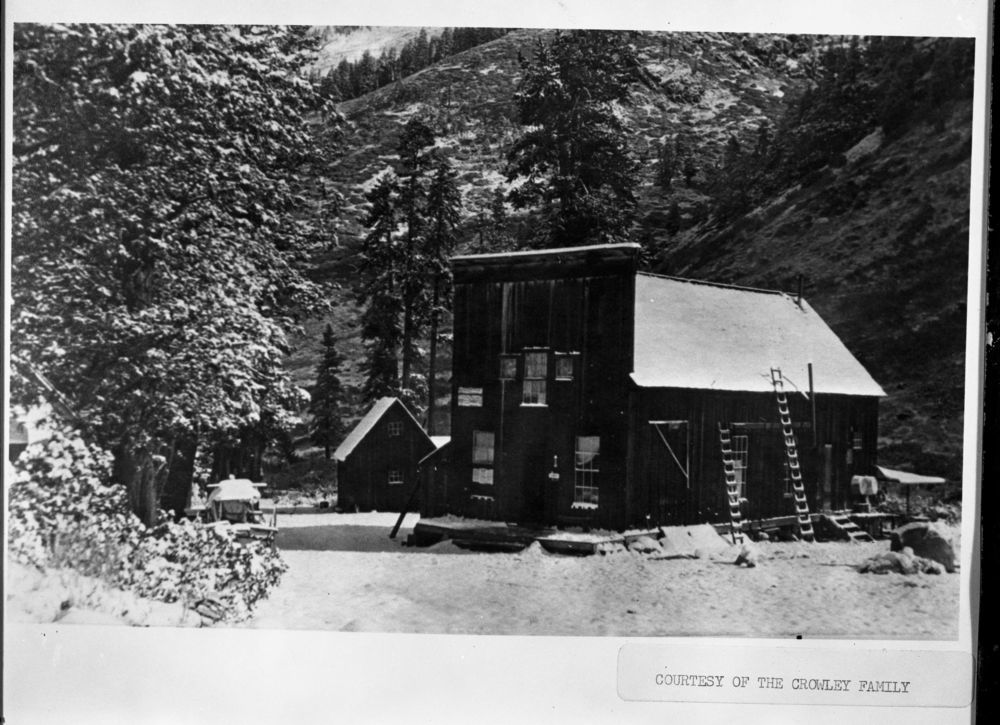

Will enjoyed taking friends to Mineral King, where they hunted and ate roasted bear head, built and launched a boat in Eagle Lake, and carried trout to Mineral Lake in a coffee can.

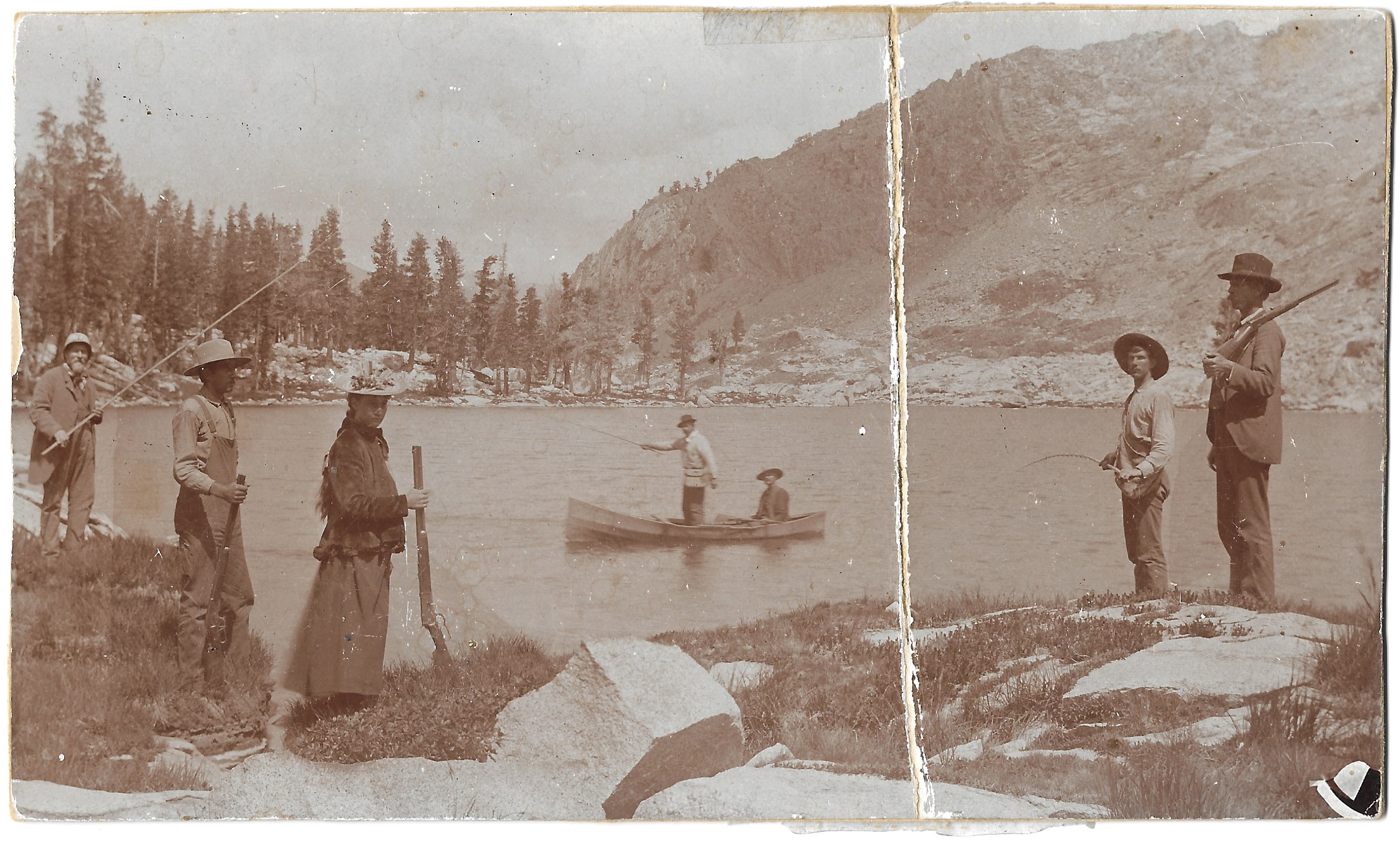

In 1897 Will Trauger left Tulare County for the mines of El Dorado. There he, Will Kenna, and their small dog set up house in a little cabin in Volcanoville. It was only a half-mile distance from Phillip’s Place, a drinking establishment that they frequented when they weren’t seeking their fortunes in gold.

On the eve of May 23, 1903, the men stumbled together out of the establishment with their dog. The spent Rubicon Mine was in the vicinity, but in the dark only the dog saw its forty-foot shaft.

The impact broke both of Will Trauger’s thighs and one of Kenna’s legs.

They had one pistol between them. They fired all their bullets up the shaft and shouted, to no avail. Eventually their voices gave way.

Their absence was not noted because they were known to go missing on account of being drinking men. Kenna purportedly kept track of the passing days on a slip of paper.

According to Kenna, after several days, our Will realized he would die. He wrote a note to Harry and Mary and provided verbal instructions on the eventual disposition of his possessions.

He then became delirious and attempted to eat Kenna, who suffered numerous bites and clawing. According to Kenna, Will died after nine days in the shaft.

On the eleventh day, the little dog was able to attract the attention of George Morrow of the Gregory Mine. Morrow followed the dog to the abandoned shaft. There he found Will dead and Kenna extremely weak. Kenna’s leg was rotting, and it was deemed unlikely that he would live long.

How could Kenna have survived almost eleven days without food and water? We can easily imagine. The state of Will’s body prompted an inquest, which mercifully resulted in a verdict of accidental death.

Will’s ending was too ghastly for Mary and Harry Trauger. They told their friends and neighbors that Will had died honorably in a mining accident in Alaska.

Over time, Will became the “angel” Mary’s son, best known for his contribution to the new resort at Mineral King. And as we have seen, Joel River Woolverton’s story was improved as well. History renamed him James Wolverton and created a hero worthy of the biggest tree in the world. A hero who fought with General Sherman to preserve the Union; a hero who met John Muir and helped preserve the giant sequoias; a hero who stood lookout to protect the new Sequoia National Park from the ravages of livestock. A hero who stayed at his post even while facing his death. …

What do we gain and lose from resurrection of the real stories? Certainly we lose the legend, but perhaps we gain an essential human connection through the less heroic and sometimes macabre truths. Regardless, we retain the story of a community that tends and celebrates even the least mighty among us.

Thus ends this series. The search for our roots goes on, however. One of the most rewarding aspects of historical research is the joy of discoveries that augment or refute what we thought we knew. If you have perspectives, stories, or evidence that would enhance or alter the tale that has been laid out in this space, please contact us.

Acknowledgments:

I am grateful to Sarah and John Elliott for hosting this series, and for their ongoing support, encouragement, and editorial expertise.

About the Author:

Laile Di Silvestro is a historical archaeologist who resides in Three Rivers, California, just outside Sequoia National Park. Her current project is researching and documenting the 19th-century mining activities in the Mineral King area of Sequoia National Park.