A History of the Kaweah Colony

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published August 2020.

When I began work on this book in 1991, the largest Marxist-inspired society in history was in the midst of collapse. Monuments to that great experiment were being destroyed — statues were toppled and walls were knocked down. Soviet communism, as established by Lenin and ruthlessly enforced by Stalin, was a distant cry from the communist utopia Marx and Engels had envisioned. Nonetheless, to more than one generation of Americans, the name Marx would forever be linked to the powerful and evil Soviet communist regime—our greatest threat and the losers in a long and bitter Cold War.

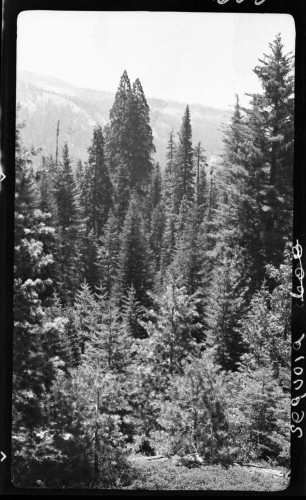

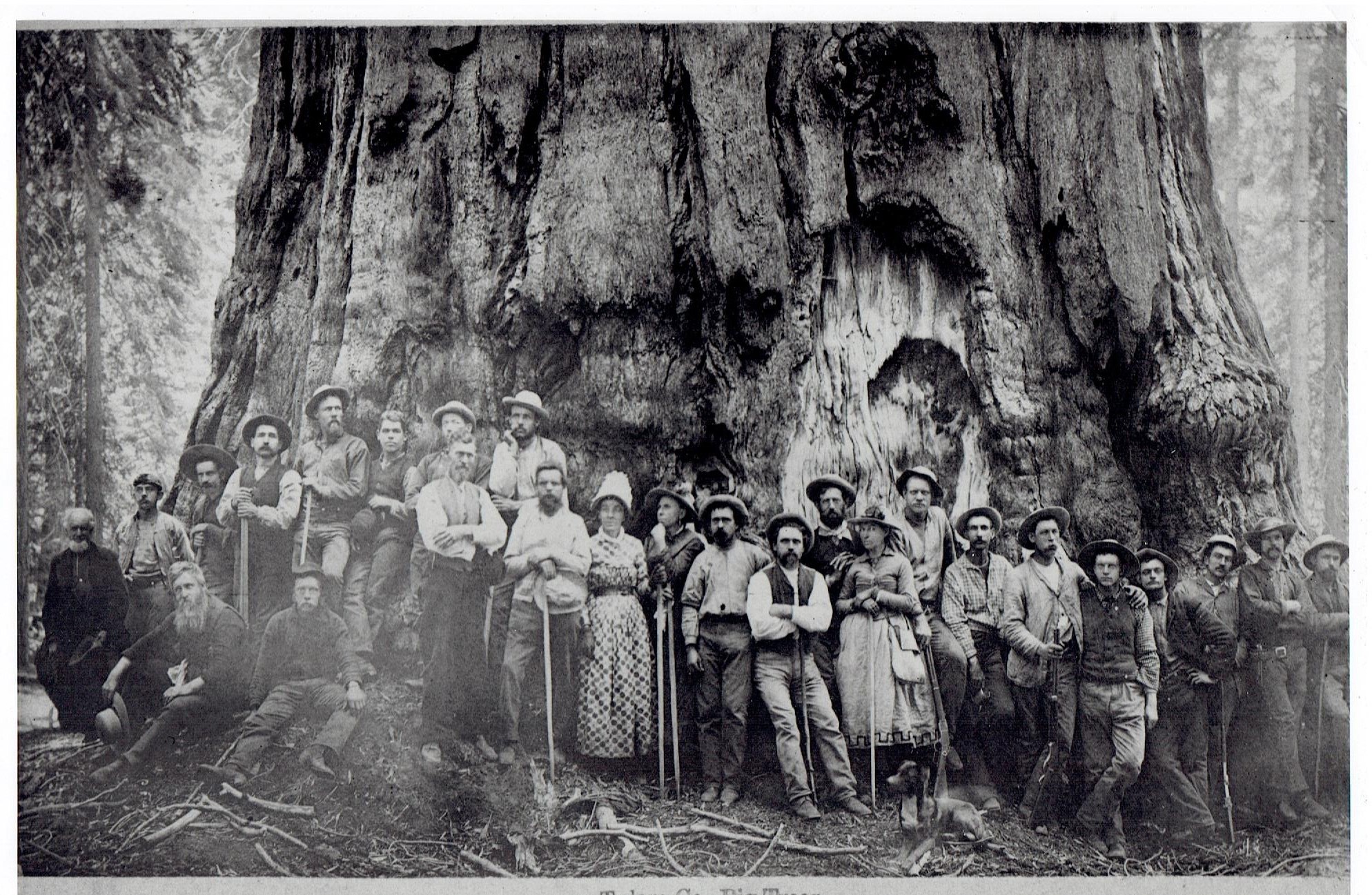

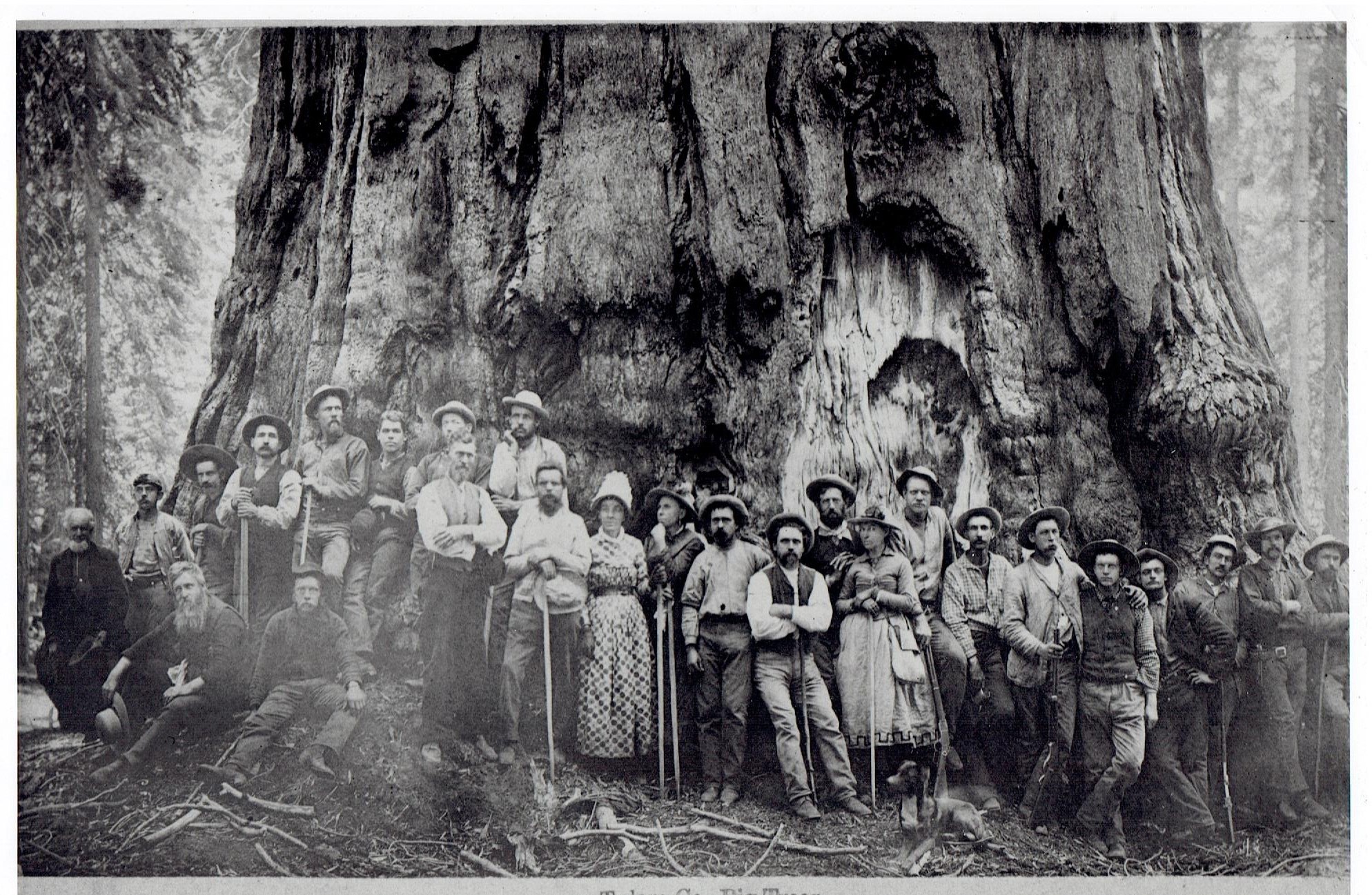

One monument to an earlier Marxist-inspired utopian endeavor still stands, even though the experimental colony disbanded 100 years prior to the recent dissolution of the great Soviet experiment. There exists an old photograph of this living monument with more than two dozen socialist pioneers standing shoulder-to-shoulder within the width of its massive trunk. The incredibly large redwood tree was christened the Karl Marx Tree by these pioneers, the Kaweah colonists. Being the largest tree in the forest (in fact, it is the largest tree in the entire world), it was given a name representing the greatest honor in their eyes.

Today, that giant sequoia is known as the General Sherman Tree and is a major tourist attraction in Sequoia National Park. Those who know the story of the 19th-century utopian experiment, however, will always partly look upon this awe-inspiring giant as a monument to a colorful and dramatic chapter of California history: the Kaweah Colony.

Having grown up in Three Rivers, the tiny foothills community at the edge of Sequoia National Park, one could say I was figuratively raised in the shadow of that giant tree. And living so near to Kaweah, the Colony’s story had always been a part of my hometown history. This is not to say that I was interested in local history. As a kid, I was only vaguely aware of this colorful chapter of our local lore, which was one part history, one part rumor, and one part myth. Rumors, when they last over 100 years, graduate to the class of myth, and there are several that surround Kaweah. I had always heard that there had been some sort of Socialist utopian commune experiment up the North Fork road back in the old days. But growing up in the 1960s in a town that attracted its fair share of free thinkers and radicals, I didn’t give the story a second thought. I just figured the Kaweah Colony was a bunch of hippies ahead of their time.

FREE LOVE AND THE CAVALRY

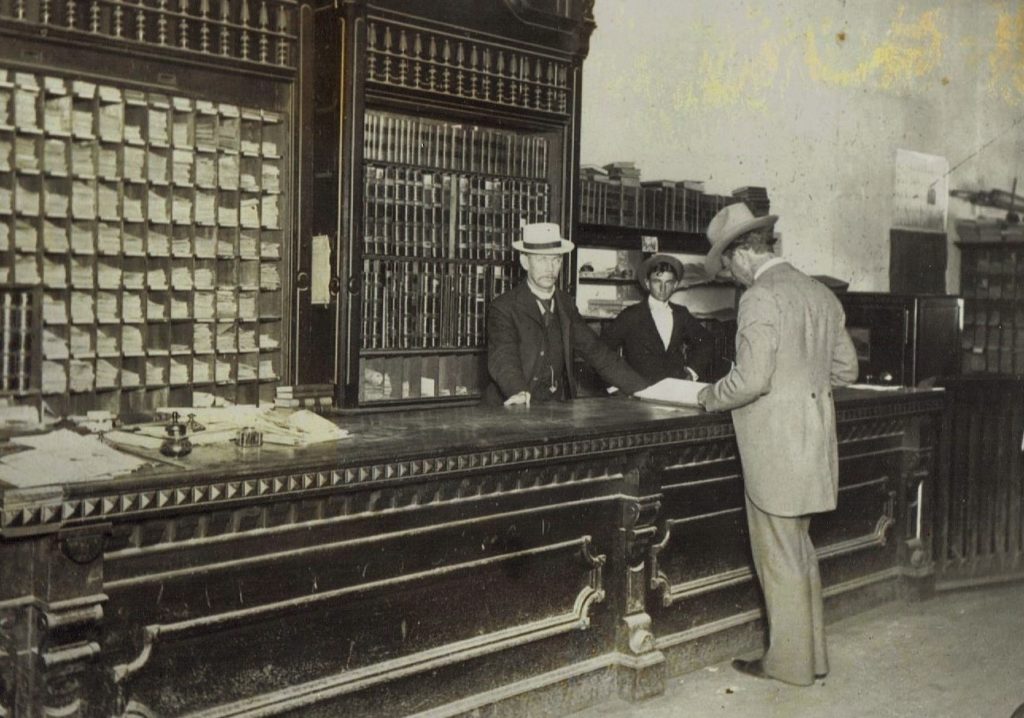

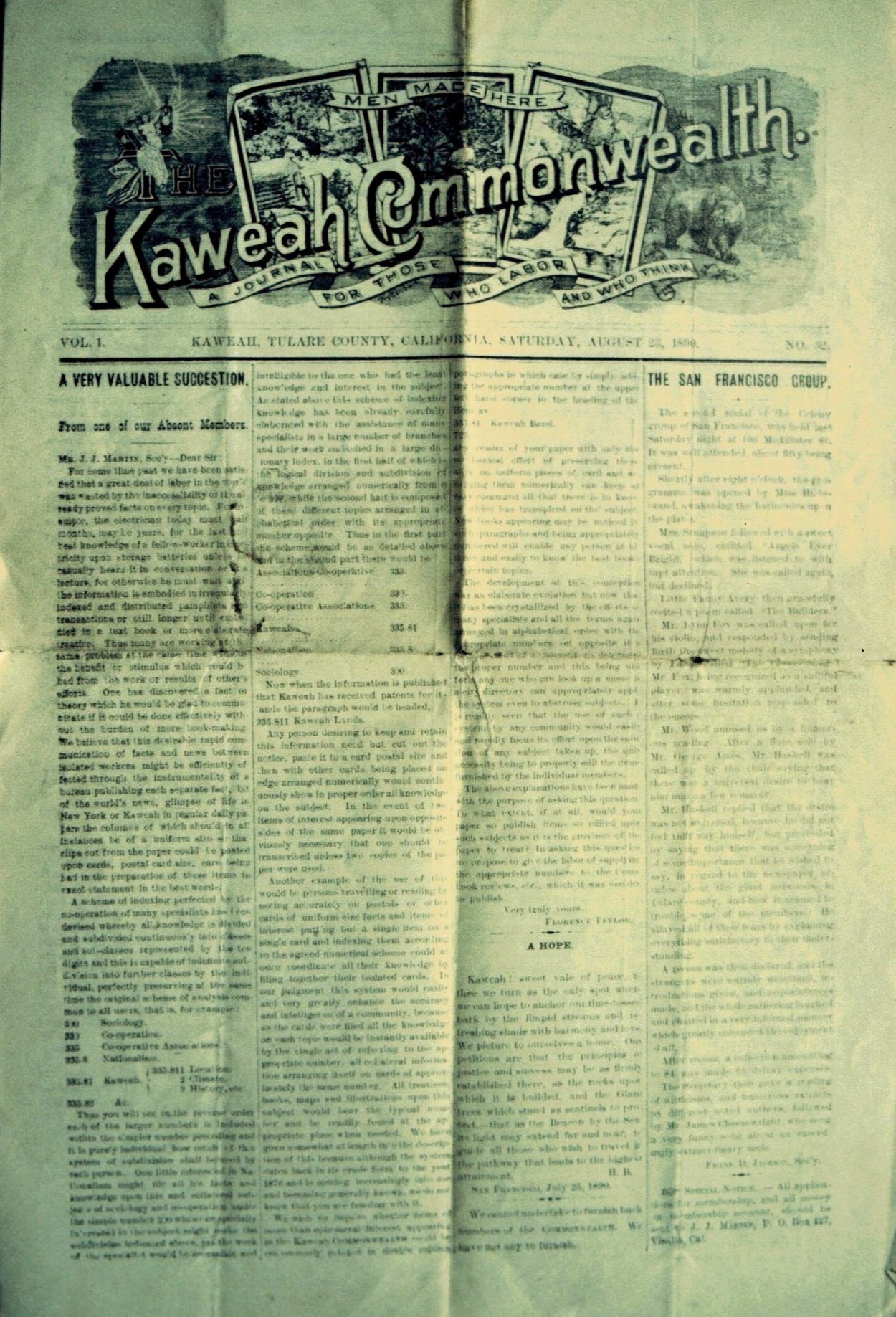

One common misconception about the Kaweah Colony is that they were generally hated by the established local communities because of their Socialist politics. Evidence to the contrary can be found in the Visalia Weekly Delta and the Tulare County Times. Both reported extensively on the Colony, generally in a favorable light. George W. Stewart’s Delta, however, ultimately turned against the Colony, but even his hyper-critical expose’ indicted the Colony leaders as scam artists and frauds rather than Socialists. Meanwhile, Ben Maddox’s Tulare County Times continued to support the Colony, printing editorials that complained of rampant persecution against them.

Proof that local businessmen supported the colonists is found in a circular, signed by the Tulare County Board of Supervisors, which appeared in both papers and stated: “These colonists as a class have proved themselves to be industrious, law abiding and worthy citizens. This treatment of them by the national administration is inexplicable.”

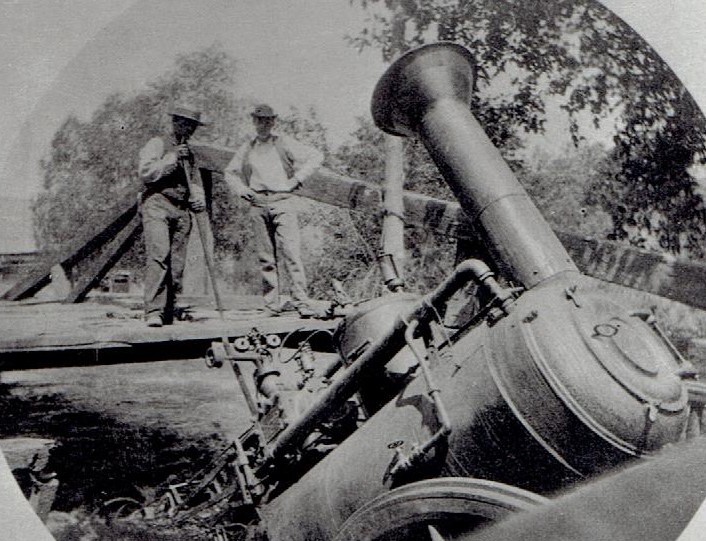

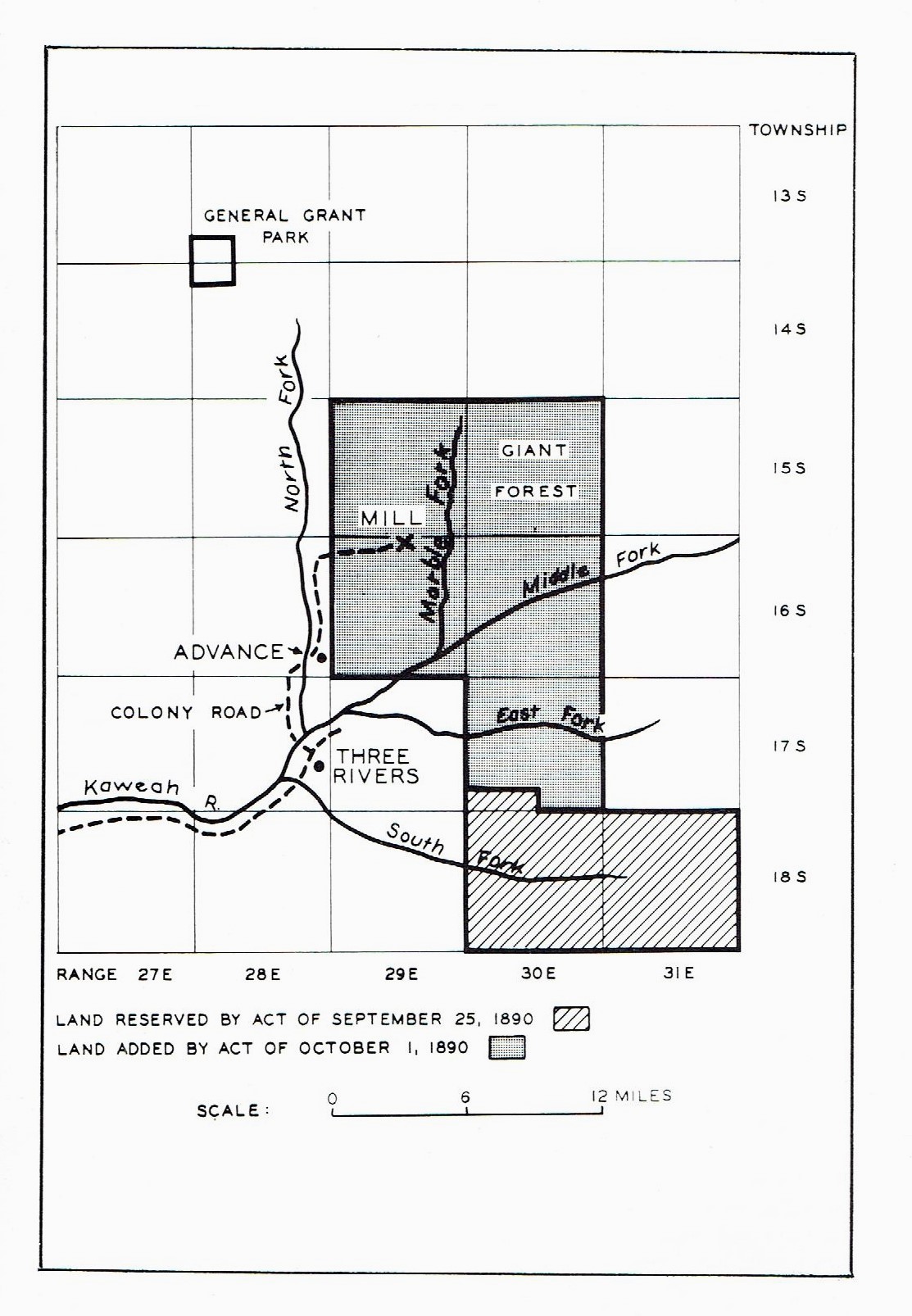

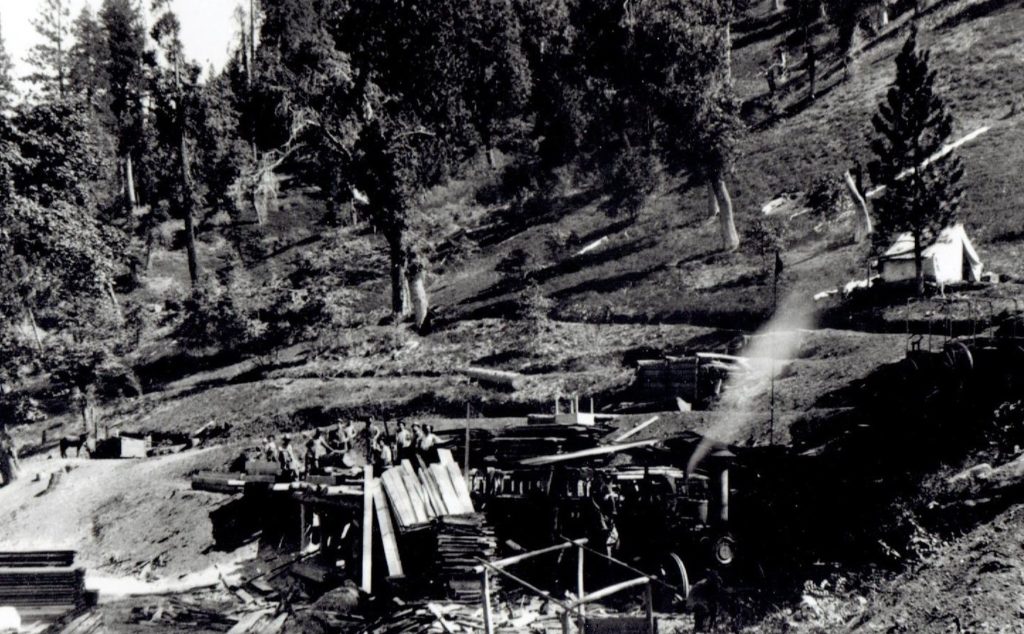

One other persistent myth about the Kaweah Colony is that the U.S. Cavalry forcibly chased them off their timber claims, thus preventing them from cutting giant sequoias. The Colony suspended logging operations on their disputed claims for a number of reasons: weather, a washed-out road, and the arrest and conviction of Colony leaders for cutting trees on government land. But the Colony’s mill was never even close to Giant Forest — the modern heart of Sequoia National Park — and so they scarcely presented a threat to that spectacular grove of Big Trees. A standoff of sorts did eventually occur between the Colony and Cavalry troops at Atwell’s Mill, an area of leased land where the Colony tried to resurrect a defunct logging operation. As we will later see, the real story is far from the popular notion of Cavalry firepower halting Colony axes, but their plan to cut timber in what is today Sequoia National Park naturally contributed to a perception that they intended to destroy the grand forests of giant sequoias.

Perhaps the most salacious and persistent rumor about the Colony was the stigma of a “Free Love” commune. One historian researching the Colony in 1960 — nearly seventy years after it disbanded — said of the Tulare County old-timers he spoke with that “everyone here is a historian. They still hate the Kaweans, and call them free lovers.”

Kaweah Colony is neither an Anarchist nor a Free Love Colony, and persons of that turn of thought are not desired nor will they be received as members.

So read a notice that ran on the back page of the Colony-published newspaper every week for several months, proving the rumors ran rampant even during the Colony’s existence. Many years later, former members of the utopian experiment were still trying to dispel the free love rumor. One local historian recalled a trip to the Colony site in 1948 with Frank Hengst, a former member:

As we explored the site, Mr. Hengst approached a spot cut in the hillside and viewed it pensively. I asked him why. “I vass yust t’inkin,” he said in his German accent, “My oldest boy, George, vass born right here in a tent.” He straightened his still massive frame. Fires of long burned-out anger rekindled in his eyes as he said: “Free-luffers, dey called us! Free-luffers!?! My vife and I haff been married fifty-fife years, and I never look at anudder voman!”

Just where these free love rumors started is hard to say. Perhaps it was due to William and Charles Riddell. It has been said they left the Colony and moved up to a secluded nearby lake where they started their own utopian community of sorts. They built two houses — one for the women and one for the men — as they did not believe in conventional marriage and outlawed intercourse. They apparently did not stay entirely true to their Shaker-like beliefs, as babies were born to the women of the group.

Another possible explanation of the free love stigma was due to an earlier American utopian experiment. The Oneida Community, founded in 1848 by John Humphrey Noyes, achieved considerable success and notoriety for several decades. One aspect of Oneida’s communalism that surely raised eyebrows was their practice of “complex marriage.” Under the system, conventional marriage was abolished and Oneida was transformed into one large “family.” Monogamous relationships were forbidden and all adults in the community were considered married to each other and thus could engage in sexual intercourse.

Though the Kaweah Colony did not condone this system, the mere fact that they, too, were an experiment in cooperative (or communal) living invited comparison to Oneida and inevitably contributed to the free love taint. Likewise, Kaweah’s Socialist ideology would logically contribute to comparisons with later experiments in Socialist (or Communist) societies.

This is the rumor-and-myth part of Kaweah’s history, and once I became more familiar with the story, I realized the necessity of peeling these layers back to try to discover the real history.

LAND, LABOR AND CONSERVATION

California, Wallace Stegner once wrote, is like the rest of the United States, only more so. Likewise, the Kaweah Colony’s story is in many ways like that of California. By examining the concentrated details of the Kaweah Co-Operative Colony’s history and the establishment of the state’s first national park, a bigger picture of California will ultimately come into frame. What started out as research into local hometown history eventually became a lesson on California and, more importantly, a shining example of the human spirit that dreamed up the Colony and settled the West.

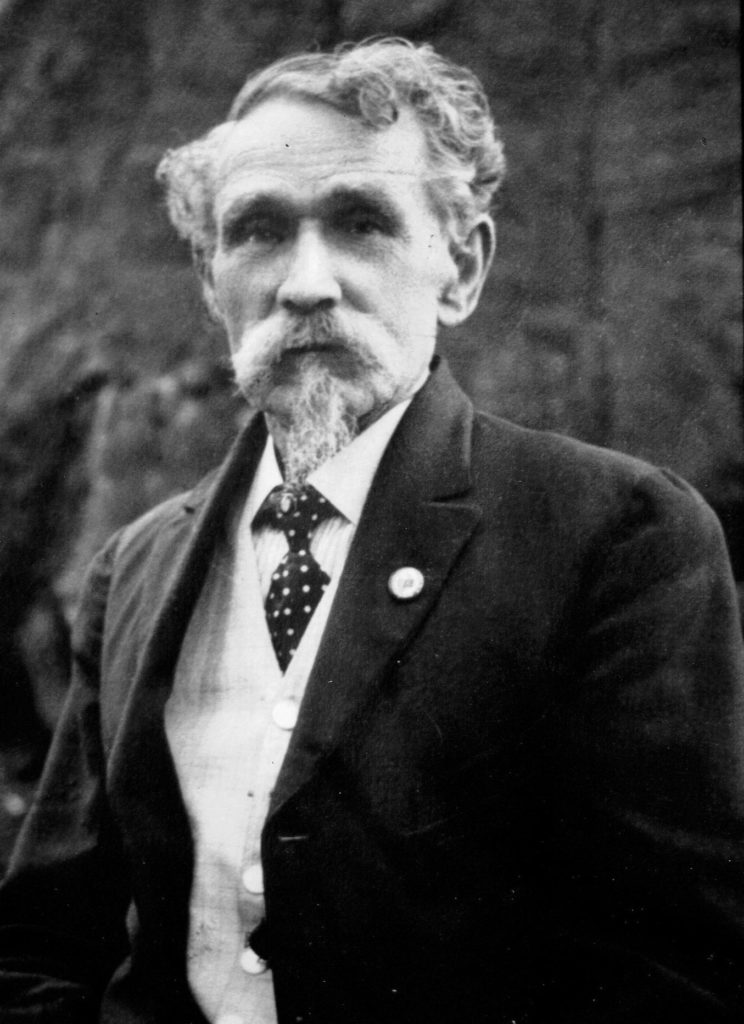

Kaweah involved far more than just a local group of early hippies. In fact, three key issues of 19th-century California history are illustrated by events at Kaweah. Land and its acquisition, labor and the organization of it, and conservation — a seemingly 20th-century concept that was very much a headline grabber in the later 19th century — are at the heart of this story. They are personified in the early chapters of this book by three major characters in the drama of Kaweah. Via Charles Keller’s experiences, we will look at land issues in California. Organized labor will find its voice through Burnette Haskell, who will in turn find his life’s calling. And conservation will be championed by George W. Stewart with an effectiveness that even he will find surprising.

Land, labor, and conservation certainly are not all there is to both the history of California and Kaweah, but during the particular period in question it is impossible to understand what was going on without closely examining the influences these three issues had. (Many will be quick to point out that one can’t even discuss the history of California without considering water. Although water certainly plays a part in the story of Kaweah, the dominance of that issue in California belongs to a slightly later period.) Any and all of these aspects of our history have been studied exhaustively, but it is how they intersect and collide, conspire and conflict leading up to and during the time of the Kaweah Colony, and it is how that conspiracy and conflict effected the outcome of Kaweah that we gain a better understanding of the history of California and indeed the American West.

The study of local history obviously helps us to know the place from which we come. My investigation into the Kaweah Colony began with a curiosity about Kaweah and Three Rivers, a place I will always consider home. It has taken me, however, to entirely new places. I have been exposed to stories and histories, aspects and issues I never would have otherwise considered. Just like great literature, art, or music, it has opened for me a whole new world.

In that world thatwe will visit — the Kaweah Colony and California in the 1880s — land, labor, and conservation all play a part in the story of a cooperative dream. In this particular story, it is a dream actively pursued by only a few hundred people, but there is no telling how many people have at one time or another dared to share the dream. It is for all of us who share that dream of a better world that this story is told.

THE HUMAN DRAMA

This is not, it should be pointed out, merely a story about issues. Nor is it history of the analytical sort, seeking to prove some theory or put forth a new argument. It is not about the dream itself, but rather a story about the dreamers. Granted, they were people who felt strongly about certain issues, and so to understand the people it is necessary to look closely at the issues that steered their actions. But, as a well-respected local historian once wrote of Kaweah, “The fascinating part is not the principle involved, but the people who made it up. They were a fairly delightful microcosm; to know them with their strengths and failings is to love them.”

Joe Doctor, who described himself as a “country journalist,” made that statement. He was long considered one of the experts on the Kaweah Colony. Everyone around knew that if you wanted information on the Colony — or just about anything else that had ever happened in Tulare County — you had better go and look up Joe. I finally did just that, shortly before his death in 1995. I had put it off for several years, out of shyness perhaps. Only after years of researching the Colony on my own did I feel qualified to go knocking on Joe’s door. I came away not only enriched for having known the outspoken, generous individual, but left with a box full of his original notes and manuscripts on Kaweah, including notes from interviews he conducted in the 1940s with surviving Colony members.

Why Joe decided to entrust me with his archive of Colony materials I can only guess. Well into his eighties and fighting cancer, he obviously knew he was close to the end. Perhaps he sensed from our discussions that I would treat the story as he always felt it should be, as a story of human drama.

“If you are half as sincere and enthusiastic as your letter reverberates,” Joe wrote me in answer to my initial request to meet him, “you are an answer to my prayers of many years; that someone would treat the Colony as it should be, a group of idealists who did their thing as human beings, and not as a socialist band of people whose motives should be criticized, rehashed, second-guessed and downgraded.”

Joe complained that some of the writers who had already written about the Colony were “academics and bureaucrats who didn’t really know what the Colony was all about.” I, at least, did not fall into either of those dreaded categories. Joe was also disappointed that a young scholar who had contacted him 35 years earlier never wrote his proposed book about the Kaweah Colony. Joe had befriended Oscar Berland, a young labor historian from San Francisco, back in the early 1960s, but theorized that Oscar got carried away “by his own socialistic-communistic convictions which ended in disillusionment,” and so abandoned the project.

As I departed from what would be our final visit, Joe urged me to follow through with my efforts on a book about the Colony. He didn’t want me to give up and disappear on him like Oscar. He didn’t want the writings of academics and bureaucrats to be the final word on Kaweah. I pledged to write this book and to let the people who dreamed of a utopia at Kaweah tell their story. I write it not as a historian, but rather as a compiler, an editor, and a referee. I have worked to present the available information in as logical, clear, and even-handed a manner as possible and let the reader, as an active partner in the process, provide the analysis and arguments. I have tried to be true to the spirit of those people involved. More than anything, I have aspired to the role of dramatist presenting a narrative, for perhaps only the dramatist can find that ever-elusive truth, if there is such a thing, in history.

SOURCES: In addition to contemporary newspaper reports from the Tulare County Times and Visalia Weekly Delta, and the Colony-published Kaweah Commonwealth, key sources for this foreword include personal papers made available to the author from both Oscar Berland and Joe Doctor, as well as “Why Kaweah Failed” by Joe Doctor in Los Tulares (No. 78, September, 1968), a quarterly publication of the Tulare County Historical Society. Maren L. Carden’s book Oneida: Utopian Community to Modern Corporation (Johns Hopkins Press, 1969) was also consulted for insight on that endeavor’s free love reputation.