Part 1: In the Shadow of the Mountain. One man’s journey from a WWII incarceration camp to the second highest peak in California.

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published February 2020.

The Mountain

“The bowl is no joke,” Tyler Hofer noted in an online account of his October 2019 trek to Mount Williamson. By “bowl,” he was referring to the lake-dotted stretch of tumbled, jagged rock that is actually more of a series of plateaus and depressions bridging the expanse below the summits of Mount Tyndall and Mount Williamson.

It was early autumn and scarcely any snow remained even at the near-13,000 foot altitude. Ironically, crossing snowfields would have been easier than boulder-hopping the jagged rock field. It was an area where you wouldn’t want to drop anything, lest it be lost in the myriad craggy crevices underfoot. And God forbid you make one careless misstep and crack your skull in the resulting topple.

Navigation was difficult. There was no real trail at this stage of the trek. Hiking guides recommend looking for a dark stain — wetted rocks high above the last lake — as a point to aim for that heralds the chute leading to Williamson’s summit.

For Tyler, a 33-year-old pastor at Torrey Pines Church in San Diego, and his hiking companion, 22-year-old Brandon Follin, a former student at the church who’d recently become a youth pastor himself, this stretch was just one more challenge in a hike that Tyler would later call the hardest he’d ever done. Tyler, who became an avid hiker and backpacker after his 2011 move to California from Nashville, had lately gotten into “peakbagging.” He had a few “fourteeners” — mountains 14,000 feet or higher — under his belt. He has summited Mount Langley, Split Mountain, and the highest peak in the lower 48: Mount Whitney.

But Williamson, the second highest peak in California at 14,379 feet high, has a reputation for being one of the more difficult. Not from a technical climbing standpoint — ropes and such aren’t necessary — but just reaching the summit entails an unrelenting 10,000 feet of gross elevation gain over 12-plus miles.

Merely getting to Williamson Bowl had been grueling for the pair. It was around noon on a Monday, and Tyler and Brandon still had hours to go before the summit. They’d left San Diego the day before, right after church, and it was dark by the time they made the six-hour drive to Independence, a community on the east side of the Sierra.

Once they had turned off Highway 395 and driven the last few miles to the Shepherd Pass trailhead over an unpaved and rutted road, it was 8:30 at night. Under a time crunch and wanting to gain altitude to acclimate before sleeping, they opted to hike in the dark. It wasn’t until 1:30 am that the two men finally reached Anvil Camp, situated at around 10,000 feet above sea level.

After sleeping in till 7:30 a.m., they broke camp and made the steep and gravel-laden trek up and over Shepherd Pass, finally dropping into Williamson Bowl. By the time they skirted around the fourth in the series of lakes decorating the bowl, they were still not sure they had spotted the so-called “dark stain.”

They both felt like they were a bit off track, but pressed on. Brandon was several yards ahead when Tyler happened to look down and saw something gleaming white between the gray tumble of granite.

“That’s odd,” Tyler thought. It looked like some kind of bone. But what kind of animal would be up at that altitude? Stopping to take a closer look, he realized it was a human skull.

“It didn’t really register immediately. I mean, was it real?”

“Hey Brandon, come check this out,” he shouted. As Brandon doubled back and got closer, Tyler told him what he thought he’d found.

Brandon’s initial reaction was “A skull? You mean like from a science classroom? Or a prop from a movie?”

The skull was partially obscured, so the two men began to move rocks off of it. It quickly became clear this was indeed a real human skull and, as they continued to remove the numerous rocks stacked on top, they saw bones peeking out. Soon, an entire human skeleton was uncovered.

“We unearthed a full-on human skeleton,” Brandon said. “Totally blew our minds. We were like, who is this guy? Why is he here? What happened?”

After taking photos and logging their coordinates so they could inform authorities, they still had a mountain to summit. With no cell reception, they would call someone later.

But the questions about what they had just discovered whirled. Theories abounded. It seemed obvious from the way the body was laid out, arms across its chest and numerous rocks covering it, that it had been buried by someone. All clothing had disintegrated, save for remnants of a leather belt and what looked to Tyler like rock climbing shoes. And it appeared to both Tyler and Brandon like the skull had been fractured on one side. Tyler surmised from some kind of force trauma, perhaps.

All this made the mystery all the more puzzling. Sinister, even. What had happened? And who had buried this person?

On the summit of Mount Williamson, they had cell reception and Tyler called the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office to report the body. They were told no one had been reported missing in the immediate area for several years. From the bleaching of the skull, Tyler and Brandon felt it had to have been there for quite some time.

But it was odd, they thought. If someone had died on the mountain, and then someone was there to bury them, wouldn’t they report it once they got off the mountain? Even a solo hiker, assuming the “burial” had somehow been natural, would leave a vehicle at the trailhead, raising alarm. Or they would eventually be reported missing by someone. But nothing.

After having summited Mount Williamson one Monday afternoon, Tyler and Brandon hiked back down and, after sleeping at Anvil Camp again that night, they returned to their vehicle late Tuesday morning. They drove to Independence and after further discussions with a Sheriff’s investigator, their discovery still seemed a mystery. It might be a long time, if ever, before this riddle was solved.

But at least the peak was bagged. Tyler could now add Mount Williamson to his list of conquered fourteeners. Brandon, newer to the peakbagging game, had notched one of the harder peaks and was now eager to conquer more.

And so, after following up with the Sheriff’s Office and leaving Independence, the two faced the long drive back to San Diego. Heading south, they saw the sign for the Manzanar National Historic Site.

“I had driven past the site many times on the 395 and had never taken the time to stop,” Tyler explained. “I am not really sure why we decided to stop that day. Maybe there was something drawing us to that place.”

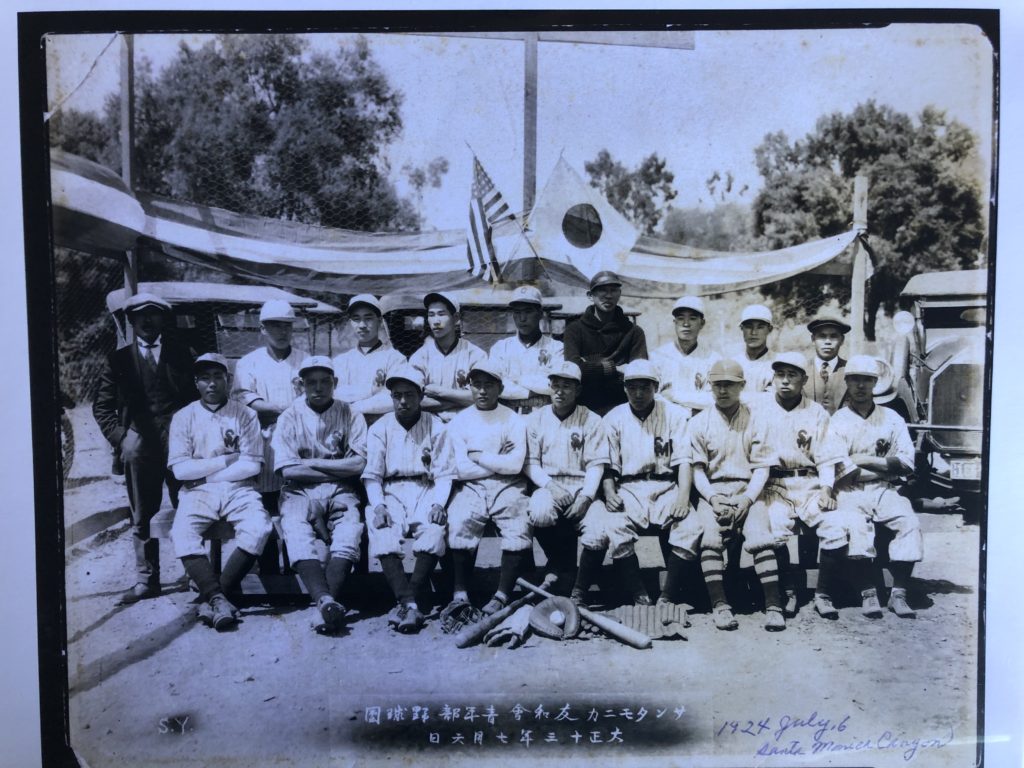

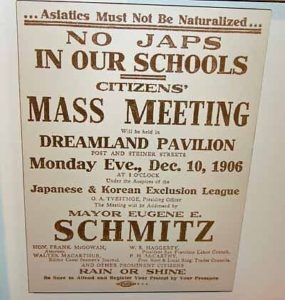

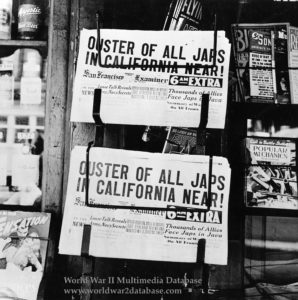

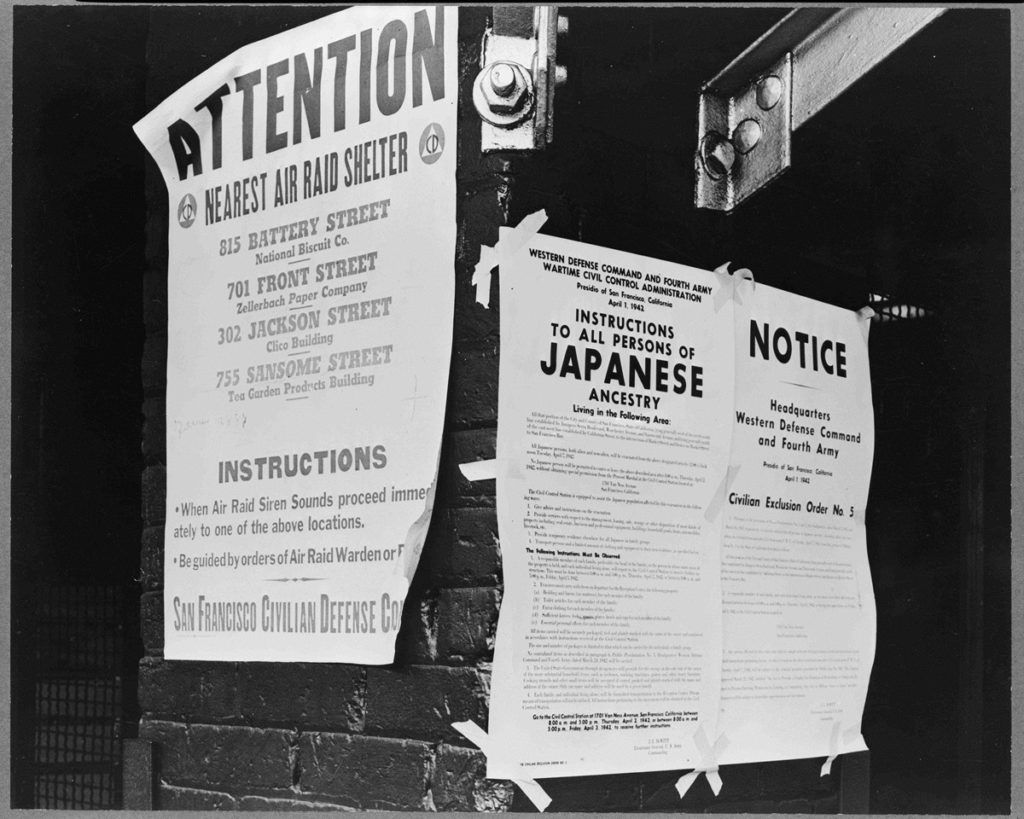

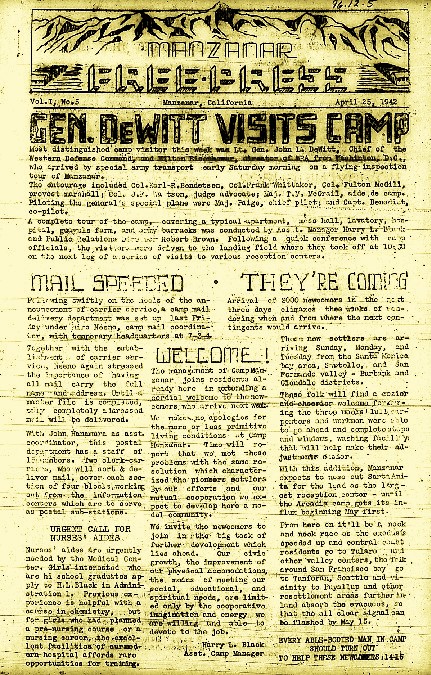

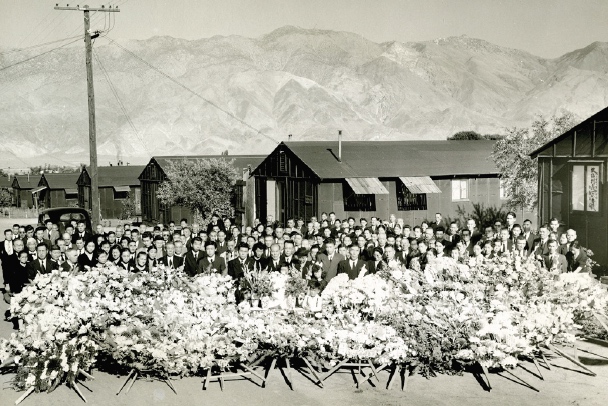

The Manzanar War Relocation Center, one of ten camps where Japanese American citizens and resident Japanese aliens were incarcerated during World War II, was built in the Owens Valley within view of Mount Williamson. Like the bones Tyler and Brandon had just the day before discovered, Manzanar also is in the shadow of that mountain.

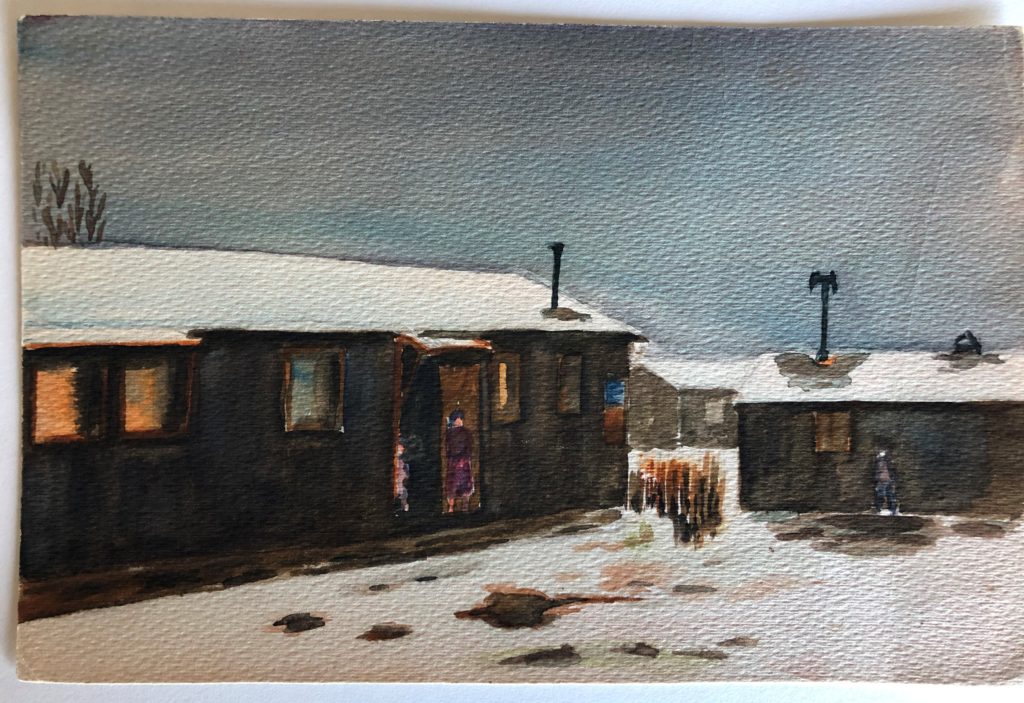

The two hike-weary men strolled the grounds of the historic site, now run by the National Park Service and open to the public. Tyler had heard stories of the internment camp, but admits he never really appreciated what it meant until seeing it in person. Going into one of the restored barracks that now serves as a historical display, he was taken with the harsh reality of living in those dorms that were so small and cramped, of people being detained against their will in such a beautiful but desolated and hostile environment. Tyler and Brandon were bone-tired and only stayed a short while.

Driving home, the topic of conversation repeatedly returned to the gruesome mystery they’d uncovered. What could possibly explain how and why someone ended up there, alone, decomposing under a cairn of stones until nothing but bare and bleached bones lay secreted in a high-country, lake-dotted bowl in the shadow of the mountain?More importantly, just who had they found, and what was this person’s story?

To be continued…

Read Part 2.

Read the entire series here.