Part 2: In the Shadow of the Mountain. One man’s journey from a WWII incarceration camp to the second highest peak in California.

The Immigrant

In the previous installment of this series, two hikers make a gruesome discovery on Mount Williamson. After climbing the mighty peak, they make a brief stop at the Manzanar National Historic Site, oddly drawn to the former War Relocation Camp. On the long drive home that follows, they cannot help but ponder the mystery behind the skeletal remains they found. Who was this person, and what was their story?

As a child in the Fukui prefecture of Japan, a coastal region where the mountains reached down to the Sea of Japan, Giichi Matsumura longed to come to America. Giichi was born in 1898, just a couple years before his father, Katsuzo, immigrated to the United States, finding work as a fisherman in Washington’s Puget Sound region.

Japanese workers first immigrated to Hawaii in 1868. When the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 cut off the supply of Chinese workers, Japanese labor filled the void. Large-scale immigration to the mainland from both Hawaii and Japan began in the 1890s.

In Japan, ship owners and emigration companies recruited workers through advertisements in daily newspapers, painting a picture of America as a land of easy money. Katsuzo was part of a wave of Japanese immigration in the early 1900s, men intent on amassing a fortune before returning home to their native Japan after a few years. The labor-intensive jobs these immigrants found hardly provided the kind of rapid economic advancement they’d dreamt of, and stays in America became much longer than originally envisioned. As a child, Giichi knew his father mostly from his mother’s stories, letters sent home, and maybe, just maybe, a photograph or two.

In 1907, immigration from Japan to the U.S. was hampered by the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement between the two countries. It ended immigration of the Japanese laboring class, but did allow for spouses and immediate family of Japanese already working in the states to immigrate. This made visits home by Katsuzo very difficult (as if the two-week voyage across Pacific Ocean wasn’t difficult enough already), but he did manage to occasionally visit his wife and family back in Japan. The 1908 birth of another son, Tadao, in Japan is clearly evidence of that.

As the years went by, immigration to America from Japan wouldn’t get any easier. And things got especially difficult for Japanese immigrants already in the U.S. In 1913, the California Alien Land Act had made it impossible for aliens “ineligible to citizenship” to own land in the state. In 1920, the Japanese Exclusion League of California was organized, prompted by newspaper publisher V.S. McClatchy and State Senator J.M. Inman. A similar organization formed in the Pacific Northwest as well. And in 1922, a Supreme Court ruling clarified that because Japanese immigrant Takao Ozawa was not a “free white citizen” he thus fell into that category: ineligible to citizenship. Key to this decision was a phrase dating all the way back in 1790, when Congress had decreed that “any alien, being a free white person” could become a citizen. While the statute would be altered when “persons of African nativity or descent” was added to the qualified list following the Civil War, that “free white person” language became very useful in denying citizenship to Japanese and other Asian immigrants.

Meanwhile, back home in Fukui, Giichi Matsumura was now a young adult, ostensibly the man of his family, which now comprised his mother, younger brother Tadao, and two sisters (further evidence his father made occasional visits home to Japan.) One consequence of the Gentleman’s Agreement limiting immigration to immediate family members was a proliferation of so-called picture brides. As spouses of those qualified to immigrate could also come to America, many marriages of young Japanese women were motivated by the opportunities this loophole afforded.

In 1923, Giichi married 21-year-old Ito Kaito, from a large family in Kyoto, a city some 100 miles to the south. An outgoing young woman of considerable sophistication and education, Ito graduated high school and had been schooled in chanoyu (tea ceremony) and ikebana (flower arrangement) in Japan. Her parents assumed she would someday help run the family business, a shop selling jewelry and elaborate hair ornaments for Geisha. But Ito wanted to go to America instead. How she and Giichi came to know each other, and exactly the circumstances of their wedding is unclear, but the couple’s youngest daughter, Kazue, nearly 100 years later claimed that “my mom married my dad so she could come [to America].”

Finally, as a young man in 1924, Giichi, with his new bride, Ito, and teenaged brother Tadao, came to California, where the Matsumura brothers were reunited with their father. Their mother and sisters would remain behind in Japan. It is unclear when the elder Matsumura ended up in California after his early time in the Pacific Northwest, but at some point he established himself as a gardener in Southern California, where he would eventually count film stars Bette Davis and Miriam Hopkins as clients and, adopting an American first name, came to be known as Harry Matsumura.

Shortly thereafter, immigration from Japan became all but impossible. Giichi and Ito had arrived just under the wire, so to speak. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed into law the Johnson-Reed Act, which included the Asian Exclusion Act and the National Origins Act. Known collectively as the Immigration Act of 1924, it effectively banned all immigration from Asia and set strict quotas for other countries outside the Western Hemisphere. The Department of State freely admitted one purpose of the act was “to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity.” And so it is little wonder that the law, so strongly endorsed by Coolidge, is widely seen today as a symbol of bigotry with white supremacist overtones. It certainly served as a harbinger of things to come for immigrant “non-white” minorities such as the Matsumuras.

Giichi and Ito settled in Santa Monica Canyon, which in the 1920s was still a fairly undeveloped area where, not unlike Giichi’s home in Fukui, the mountains met the sea. Some of the residents of the canyon, such as the Marquez and Reyes families, had land that dated back to Mexican land grants of the 1830s. The natural beauty of the area also attracted a number of prominent residents, including Juan Carrillo, who would later become the first mayor of Santa Monica and whose son, Leo, became a film star and favorite son of Santa Monica. (Today, Leo Carrillo Beach is a popular attraction near the mouth of Santa Monica Canyon.)

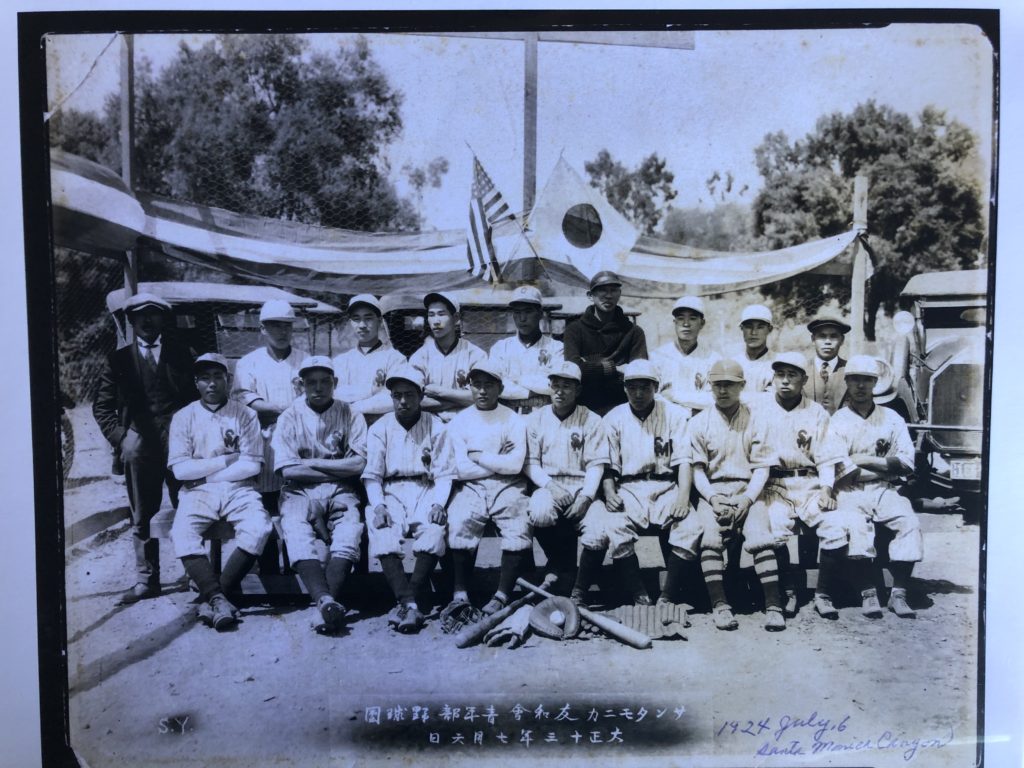

When Giichi and Ito came to the canyon, they lived with Giichi’s father, renting a small house from the Marquez family on their property near an abandoned old adobe. Giichi, like his father, found work as a gardener. The young couple quickly sought to integrate into Santa Monica Canyon society. Giichi took part in that quintessentially American activity: baseball. In a photograph dated August 1924, he and his brother Tadao are in a team photo, the letters SM proudly emblazoned on their uniforms, an American and Japanese flag situated behind the team. (Baseball had long been popular in Japan, it should be noted, as well.)

Ito also wasted no time integrating into American life as much as she could, going and sitting in the classroom of the local elementary school — Canyon School — in order to learn English. (The Canyon School, founded in 1894, remains a vital part of the community today.) She also helped bring Japanese culture to the canyon, assisting in a Japanese School started in the old adobe hut on the Marquez property behind their house where she taught tea ceremony and flower arrangement.

In 1925, Giichi and Ito had their first child, a son they named Masura. One can imagine Giichi was perhaps grateful that his boy was something Giichi could never be: a citizen of the United States of America. His son would be afforded all the protections that came with that privilege. Giichi would teach his son to cherish this, and perhaps someday show him the Bill of Rights, which guaranteed those inalienable rights.

So while Giichi Matsumura could never become a citizen and couldn’t even own land in California, he could raise an American family, and that is exactly what he and Ito set out to do.

* * *

On October 16, 2019, more than a week after Tyler Hofer and Brandon Follin (see Part One) made their startling discovery of a skeleton on Mount Williamson, CHP Inland Division Air Operations was able to assist the Inyo County Sheriff’s Investigators and the anonymous remains were successfully transported from Williamson Bowl to the Lone Pine Airport where custody was transferred to the Inyo County Coroner.

News of the hikers’ gruesome discovery ran in newspapers throughout the country that very day. The story was first reported by Brian Melley of the Associated Press. The report echoed the sense of utter mystery Tyler had noted in a California Mountaineering Group Facebook post he made a couple days before Melley’s story broke.

“Had something truly unique happen to me on my recent summit of Mt. Williamson,” Tyler wrote, and concluded his account of the discovery by asking the mountaineering group if “anybody has a theory as to what could have happened.”

Melley’s thorough reporting included Tyler’s story and thoughts, along with comments from the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office that, while downplaying any hint of foul play pondered by Tyler, claimed nonetheless that “this is a huge mystery for us.” They noted they had ruled out recent missing persons such as trans-Sierra skier Lt. Matthew Kraft (missing since February 2019) or Matthew Greene (missing since July 2013), a climber who was camped in the Mammoth area.

But neither Tyler Hofer nor Brian Melley had any idea that authorities already thought they knew the answer to the mystery. Only two days after the remains were discovered, the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office informed park rangers at the Manzanar National Historic Site about the discovery and told them just who they thought it was. Their theory made perfect sense to the staff at Manzanar. But until identification of the remains could be confirmed, both the Sheriff’s Department and Manzanar were keeping quiet about just whose bones might have been discovered high up on Mount Williamson.

In the next installment, life in Santa Monica Canyon is disrupted for the Matsumura family by world events, and they suddenly find themselves experiencing life behind barbed wire in a remote area of eastern California.

Read Part 3.

Read the entire series here.