Part Nine: The Long Feud

By Laile Di Silvestro. Published March 2025.

This is Part Nine of a multi-part series by historical archaeologist Laile Di Silvestro. The series started with an astonishingly bold act—two women staking a claim in the remote Mineral King Mining District in what is now Sequoia National Park. The tale unfolds in California in the second half of the 19th century. It was place and time where women struggled to thrive within power structures that favored unscrupulous men. It is a true story. Read Part Eight HERE.

While his nephew Frank was on trial, Edwin was facing trials of his own. Or perhaps his own making.

Edwin, however, might have blamed his troubles on his voracious sheep.

The “hoofed locusts,” as naturalist John Muir called them, needed to eat, and they weren’t picky about the location of their meals. They’d just as happily eat a farmer’s crops as consume all the vegetation in a mountain meadow.

The sheep, pig, and cattle ranchers had dominated the San Joaquin Valley in the 1860s. However, as the agriculturalists built ditches to divert the water flowing into Tulare Lake—once the largest lake west of the Mississippi—more land opened up for farming. Thus the “world’s food basket” was born. Within the valley’s confines, the conflict between the farmers and ranchers was inevitable.

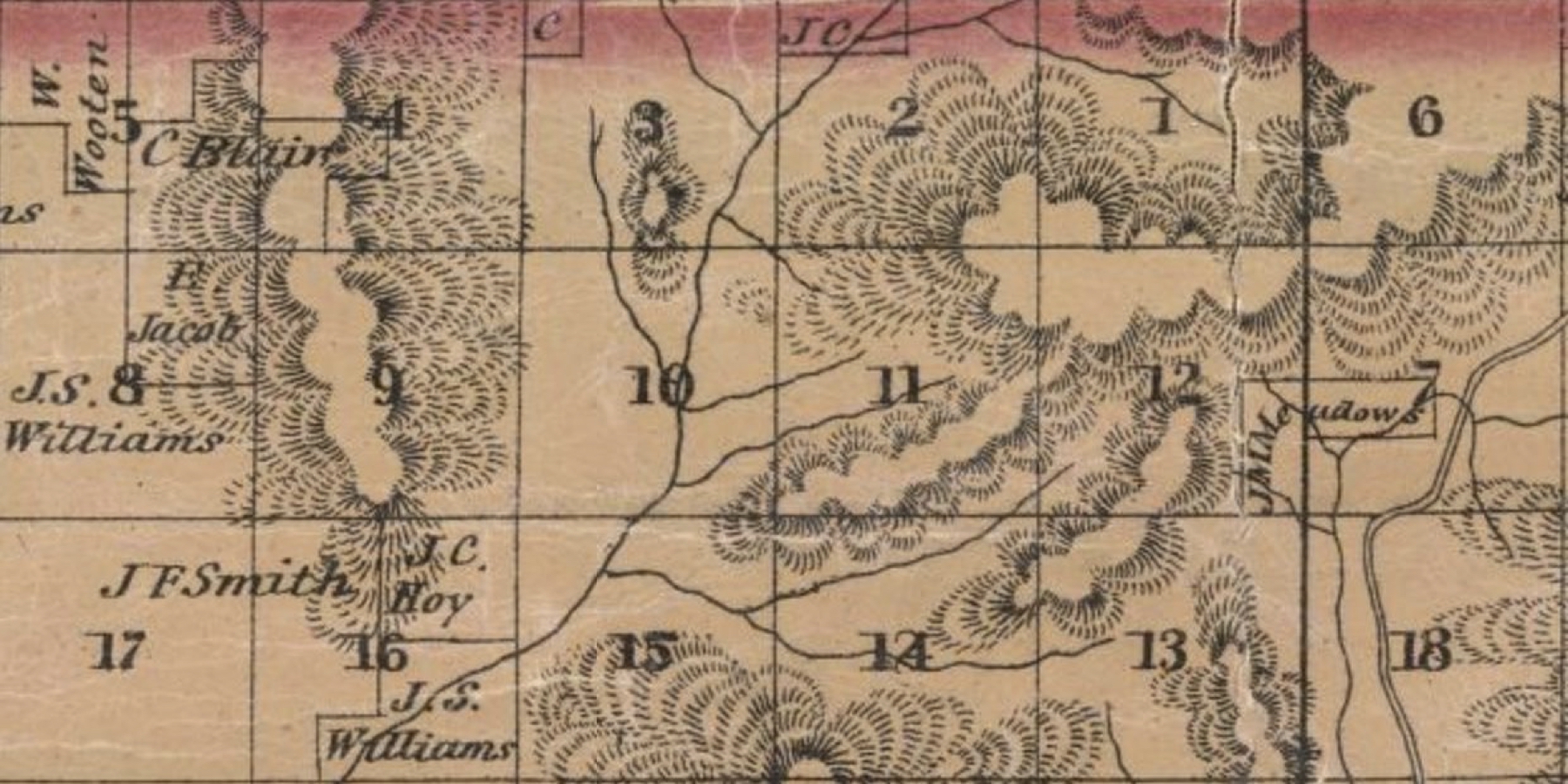

Near the banks of Sand Creek, the regional conflict came to a barb-sharp focus on one indisputable fact. Edwin’s livestock had a tendency to get into the fields of Charles H. Wilson. Charles had little patience for this. Edwin had little patience for Charles. The situation escalated for years with the men occasionally coming to blows. Then morning dawned on 20 September 1882.

On that day, Charles went to the Gilkey home to confront Edwin. Words escalated into physical violence, which Edwin dominated as the larger man. One report indicates, however, that Edwin wasn’t just giving Charles a “lashing,” but was actually hitting Charles with a whip. When Charles begged for mercy, Edwin stopped and turned away. At that point, Charles shot him in the back.

Charles claimed self defense, but was found guilty of murder in the second degree and sentenced to 25 or 30 years in prison.

The sentencing didn’t change the fact that our Mineral King miner Ellen Gilkey was now a widow. It is likely that she moved in with Lizzie and George. Nevertheless, perhaps broken by stress and grief, she died before the spring of 1888.

To be continued…

Read Part 10.

Read the entire series here.

Sources:

Census records (Tulare County County, CA)

Ludeke, John. 1980. “The No Fence Law of 1874: Victory for San Joaquin Valley Farmers, ” California History, 59(2):98-115. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Menafee, Eugene L. and Fred A. Dodge. 1913. History of Tulare and Kings counties, California, with biographical sketches of the leading men and women of the counties who have been identified with their growth and development from the early days to the present. Los Angeles: Historic Record Co. See pp. 46-9.

Preston, William L. 1981. Vanishing Landscapes. Berkeley: University of California Press. See pp. 90-5, 130-44.

The Daily Examiner (San Francisco). “Found Guilty of Murder.” 15 December 1882, p. 3.

The Daily Examiner (San Francisco). “Pleas for Mercy: Imprisoned Convicts Who Want their Liberty.” 18 July 1885, p. 3.

The Daily Examiner (San Francisco). “Prison Commission: More Applications from Convicts for Pardons.” 24 December 1885, p. 3.