Part 4: In the Shadow of the Mountain. One man’s journey from a WWII incarceration camp to the second highest peak in California.

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published February 2020.

The Camp

In the previous installment, after the attack on Pearl Harbor and Executive Order 9066, forced evacuation of Japanese Americans began. In April 1942, the Matsumura family was ordered from their home in Santa Monica Canyon and boarded a bus headed to incarceration at a desolate camp in the high desert of eastern California.

Lori Matsumura was surprised when, in October of 2019, the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office contacted her to say they believed her grandfather’s remains had been discovered on Mount Williamson. Investigators asked the Santa Monica resident to provide a DNA sample for comparative testing.

Lori’s family had always known her grandfather, Giichi Matsumura, was buried high in the mountains above Manzanar, but the story had faded over time and the exact location of his final resting place was lost to time. Had the grandfather she never knew indeed been “rediscovered”?

Lori’s father, Masaru Matsumura (Giichi’s oldest son), had been incarcerated at Manzanar as a teenager. Like many who endured the hardship and humiliation of that dark chapter of American history, he seemed bitter and rarely spoke of the camp. Masaru died in 2019 at the age of 94. Lori now wishes she had dug a little deeper, asked questions, and found out more about what had happened to her family during their days at Manzanar.

* * *

After President Roosevelt created the War Relocation Authority in March 1942, efforts to evict Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast accelerated. The ensuing mass removal took place in two phases.

First, people of Japanese ancestry were sent to live in temporary prison camps, euphemistically called “assembly centers.” Most of these temporary facilities were hastily built at racetracks and county fairgrounds near coastal population centers. Families were forced to share one-room barracks built of plywood and tarpaper. Worse, many had to actually live in animal stalls, as there was a shortage of human barracks at these often makeshift facilities.

Then, as permanent incarceration camps in remote parts of Western states (and one in Arkansas) were built, displaced Japanese Americans were relocated there, often via long train or bus rides many hundreds of miles, for the duration of the war. Eventually, by the end of that summer of ’42, there would be ten camps that held more than 110,000 incarcerees, and approximately two-thirds of those were United States citizens.

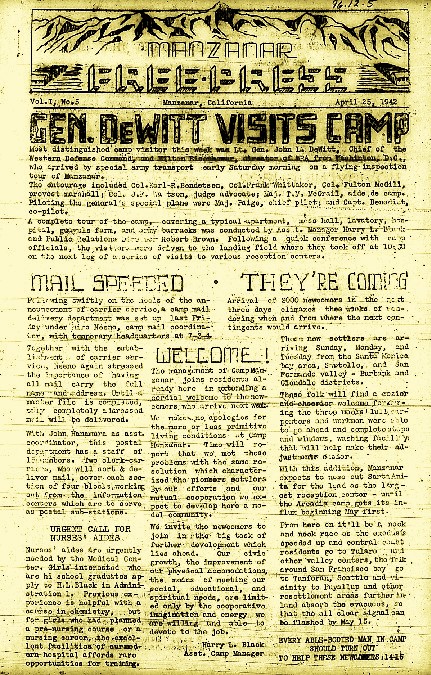

On April 25, 1942, the Manzanar Free Press, under the headline “They’re Coming,” heralded the imminent arrival of 2,000 “new settlers” to the camp situated just east of the Sierra Nevada crest and over 200 miles north of Los Angeles. With an offensively cheery tone, the government-published newspaper admittedly made “no apologies for the more or less primitive living conditions at Camp Manzanar,” but predicted that “by our efforts and our mutual cooperation we expect to develop here a model community.”

Having received the Exclusion Notice, the Matsumura family was ordered from their home and given a location where they would board a bus. A little girl of six at the time, Kazue Matsumura only remembered being excited about the bus ride. To imagine what she must have thought as the bus made the all-day journey up through the Owens Valley and finally to Manzanar, consider the recollections of another young Japanese American woman who made a similar journey.

“I could see, way out yonder in the desert, all these barracks and some men without their shirts on, cause it was so hot. I said to the person next to me, ‘Oh, I am so glad I don’t live in a place like that.’ What do you know, the bus turned right in there, and I’m telling you, my heart sank down to my toes.”

Seventy-five years later, Kazue only remembers it was a desert, “nothing there, just dirt.”

At least Giichi and his family weren’t sent, like most in the Los Angeles area, to the assembly center at Santa Anita. Conditions at the race track were miserable, with many families actually forced to live in horse stables. But Manzanar, which served originally as an assembly center, and later — when construction was nearing completion — a permanent camp, didn’t boast of conditions much better.

New arrivals to Manzanar were issued an army cot and had to make their own mattresses by stuffing a sack with straw. Giichi and Ito, along with their four children and Giichi’s elderly father, lived in a single 20-foot by 20-foot room. Construction of the barracks had been slap dash, often using wood planks that were still green. When the boards dried, they shrank, and sand and dust would come in through the resulting cracks.

The winds at Manzanar could be relentless. People living in these barracks would sometimes wake up in the morning covered with sand, faces grimy with dirt. Conditions were bleak, and the desert environment harsh.

Originally assigned to Block 16, where a school would soon be built, the Matsumura family relocated to Block 18 at the far western edge of camp. Giichi’s brother, Tadao, and his family lived in Block 13, way on the other side of camp. Both Giichi and Ito worked while living at Manzanar. Giichi started off working in one of the mess halls, but his daughter Kazue remembers that he worked outside the camp, having something to do with “watching a water tank.” (He probably worked tending the system of reservoirs and storage tanks that supplied the camp with water. It was one of many jobs incarcerees performed outside the camp border.) Ito washed dishes at the Block 23 Mess Hall.

Giichi’s children attended school at Manzanar. His oldest, Masura, unable to finish high school with his good friend Ernie Marquez back in Santa Monica Canyon, was part of the first graduating high school class of 1943 at Manzanar. The other two boys also attended high school while incarcerated. Giichi’s youngest, who had only briefly attended first grade back at the Canyon School, suddenly found herself in third grade at Manzanar. She doesn’t remember ever being in second grade.

Those incarcerated at the camp did their best to persevere in the face of the unendurable and to do so with dignity. The Japanese had a term: Gaman. Making do. And beyond just making do, many in camp found ways to find enjoyment. Even behind barbed wire and even after having left their homes and most everything they owned behind, even after all that, they sought to make life worth living.

Baseball was incredibly popular at Manzanar. It’s a safe bet that the Matsumura boys played on one of the many teams at camp. Based on Giichi and Tadao’s days on a team in Santa Monica Canyon back in the 1920s, one can imagine the Matsumura men also took part in the popular pastime. After all, Tadao was still a young man in his 30s and even Giichi, in his mid-40s, was still capable of playing the sport so popular in both his homeland and adopted country.

Giichi undoubtedly also utilitzed his gardening skills while at Manzanar. From the very first months of the camp’s existence, residents did all they could to transform the barren desert environs, which Kazue aptly described as “nothing but dirt,” into a lush, beautiful landscape. Although a daunting task, many of the Blocks soon boasted elaborate Japanese gardens.

The Manzanar Free Press, reporting on a garden contest in the November 5, 1942, issue, stated the Block 34 garden, which “boasted generous green slopes and dips, a fish pond, and different greenery,” was judged the winner. Close second was an entry from Block 22 with a huge fish pond of interesting design. It is not known if Giichi and his Block 18 neighbors entered the contest, but they were not reported as among the contest winners.

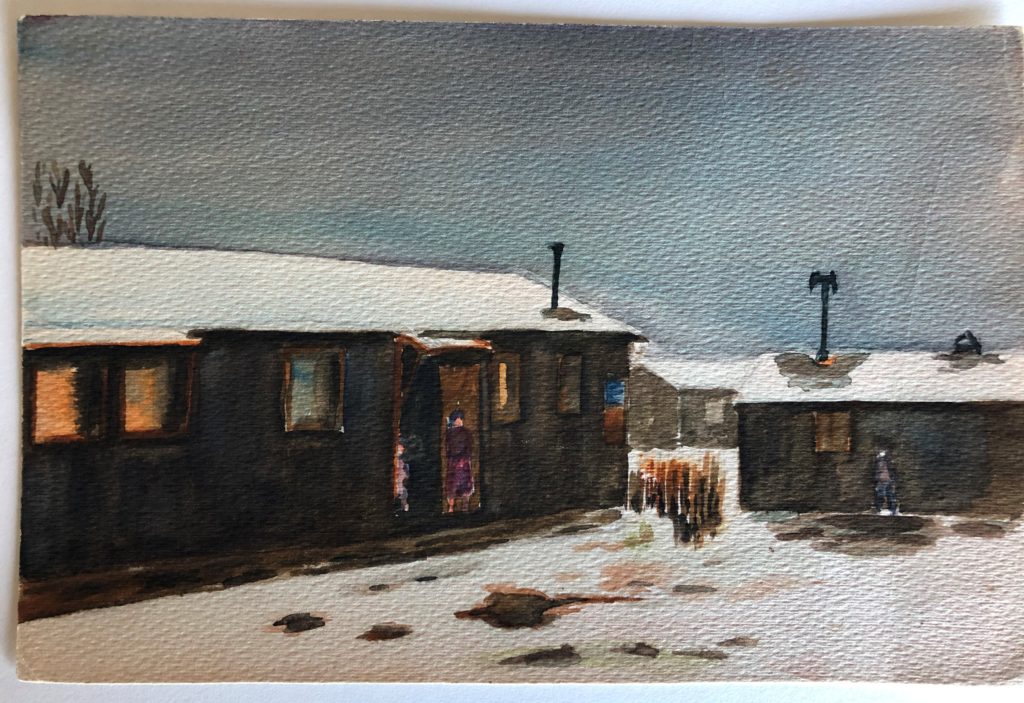

But Giichi did do something else to create beauty amidst the harshness of incarceration. He took up painting while at Manzanar, which according to his daughter he had never done before. Scenes of the camp and the view of the nearby mountains were the subjects of his watercolor paintings. Through his newfound art endeavors, Giichi was able to find beauty, albeit a desolate and harsh beauty, in the everyday world around him. A peaceful, beautiful method of Gaman.

Things were far from peaceful and beautiful, however, as time passed at the camp. Regardless of the baseball games and gardens, it was still a prison.

In late 1942, an incident that came to be known as the December Riot resulted in the institution of martial law at the Manzanar. It culminated with Military Police firing into a crowd of inmates, killing two and injuring many. The incident was triggered by the beating of a Japanese American Citizens League member upon his return from a meeting in Salt Lake City, and the arrest and detention of another incarceree for that beating.

The following year, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority joined forces to create a bureaucratic means of assessing the loyalty of those in the camps. All adults were asked to participate in a “loyalty questionnaire,” which only succeeded in provoking upheaval.

Two questions most disturbed the incarcerees:

“Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?” and, even more troubling, would they swear unqualified allegiance to the U.S., defend it from attack by foreign or domestic forces, and “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization.”

This only exacerbated tensions. Many who answered no to these two questions — “No Noes” as they came to be called — would end up relocated to the even more desolate and harsh Tule Lake camp, which was in effect a high-security concentration camp. Giichi and his sons apparently did not answer no to either of these questions, as the Matsumura family all remained together at Manzanar throughout the war years.

But this doesn’t mean there wasn’t a desire to escape the prison walls, to bound out beyond the barbed wire. Some men did more than just dream of such freedom. Some men at Manzanar found a unique way to assert their freedom, if only for a few brief peaceful respites. Giichi was friends with some of these men, and that association would cost him and his family dearly.

* * *

Filmmaker Cory Shiozaki, like many Japanese Americans of his generation, never heard his parents talk about what happened to them during the war. Like many who suffered the indignity of forced relocation and incarceration, Cory’s parents spoke little about the hardships they had endured. Indeed, Cory did not even realize until he was in college that his parents had even been incarcerated.

As a young man he decided he would one day tell this story of mass roundup and incarceration. But he didn’t know exactly how he would focus a lens on the story. Decades later, when he saw a Los Angeles Times article that featured a photo of a fisherman holding a stringer of trout taken at the Manzanar prison camp during the war, Cory knew he had found his angle.

In the next installment, as the months and years drag on at Manzanar, a group of men assert their freedom, if only for brief respites, by going fishing. Giichi envies these men and, ultimately, after years in camp and with war’s end in sight, seeks to join them in one last excursion.

Read Part 5.

Read the entire series here.