Part Four: The Lynching

By Laile Di Silvestro. Published March 2025.

This is Part Four of a multi-part series by historical archaeologist Laile Di Silvestro. The series started with an astonishingly bold act—two women staking a claim in the remote Mineral King Mining District in what is now Sequoia National Park. The tale unfolds in California in the second half of the 19th century. It was place and time where women struggled to thrive within power structures that favored unscrupulous men. It is a true story. Read Part Three HERE.

You may have noticed that when Lizzie’s uncle William Tibbetts Gilkey intervened in the 1855 gunfight on the streets of Sonora, the local sheriff was notably absent. He did try to maintain the peace and support due process; however, he did so at the risk of his own life. On one occasion a bullet narrowly missed him as vigilantes endeavored to wrest some criminal suspects out of his protection. Despite the sheriff’s efforts, two out of six executions were conducted by lynch mobs rather than government officials.

When William and his family moved to the town of Pajaro in Monterey County* in about 1866 it was no different. He rapidly established the same aura of respectability and reason there as he enjoyed in Tuolumne County.

And vigilante law ruled.

To a certain extent, William had his charismatic, angry, and drunken brother Melvin Jerome to blame for what happened. While William became a well-respected fruit grower, Melvin scraped by as a skilled carpenter and millwright. Melvin railed against a legal system that favored some, actively harmed others, and failed to protect the rest. To be precise, he didn’t just rail against the system, he declared himself the sworn enemy of the men who ran it. And Melvin was known for being outspoken and absolutely fearless.

When Lizzie and her family joined William and Melvin in Pajaro in the late 1860s, the situation was tense. Melvin’s sworn enemies were powerful and arguably corrupt Southern Democrats with bullying, abrasive personalities. After the Civil war, the Democrats had lost some of their power. As the 1868 election approached, these men took action.

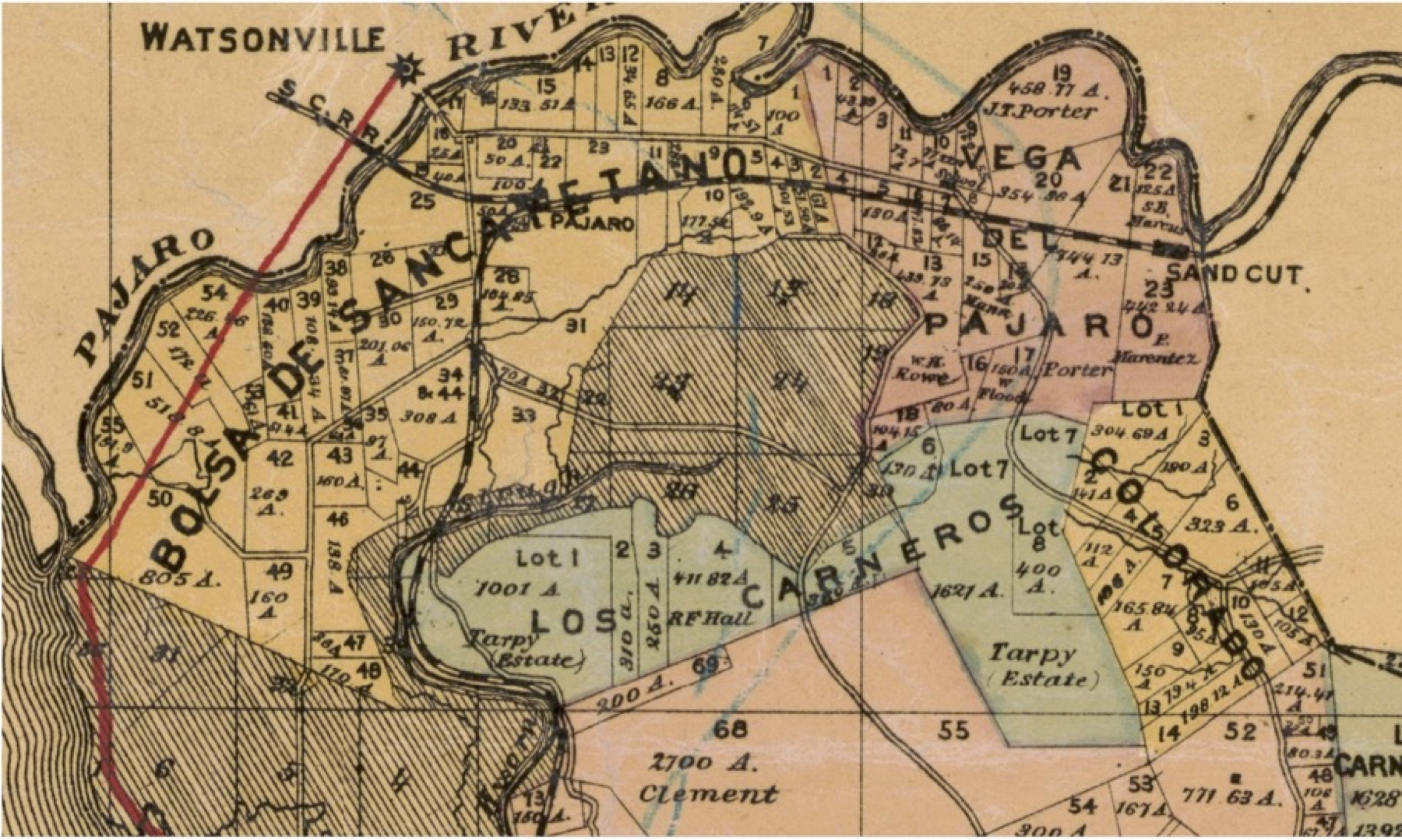

Fueled by racism, the men had been allowing Irish and German immigrants to illegally seize the land of Mexican Americans, and indefinitely delayed the resulting court cases. An Irishman named Matt Tarpey was one of the beneficiaries. As the election approached, the Democrats forged naturalization papers to enable these men to vote. Again, Matt Tarpey was one of the beneficiaries. The Republicans allegedly raised $5000 to battle Tarpey and twenty-two other local immigrants. In a showcase trial, Tarpey was acquitted after it was claimed that the Republicans had used this money to bribe witnesses. The next day, all the others were acquitted as well.

Melvin Gilkey, his younger brother John, and their Republican friends were incensed. The Republicans responded with a media campaign accusing the Democrats of treason against the United States during the recent Civil War. The outcome was mixed, but the Democrats regained local control, winning the lucrative and powerful offices of judge, sheriff, county clerk, treasurer, auditor and recorder, and coroner.**

Melvin’s wife Emeline died shortly after the 1868 election. Did the local doctor, the Democrat leader named Dr. Chester Edwin Cleveland, try and fail to save her? We may never know. But it was about this time that Melvin began to threaten to kill Tarpey, Cleveland, and other Democrats.

Tarpey was at this point the recognized leader of the ranchers and farmers of the region. He was about 48 years old, short and stout, with a sandy mustache and balding head. He was also a profoundly racist vigilante. With the support of the local Democrats, he had established the Pajaro Property Protective Society. With Tarpey at the head, the vigilantes rounded up and lynched Native Americans and Mexican Americans, many of whom were assumed to be innocent. The voracity and cruelty of Tarpey and his men shocked many members of the community, and alarmed residents of surrounding regions concerned by the upwelling of mob rule.

Meanwhile, Tarpey had amassed 1500 acres, and was continuing to acquire land and retake property that he had sold. Once again, he was helped by the court system, which delayed the resulting legal cases. In 1873, Tarpey decided to log a section of land he had sold to Murdock and Sarah Nicholson in 1868. The Nicholson’s turned to the legal system for help, but in March 1873, Tarpey placed a cabin there to establish possession.

Sarah’s husband was away, but that didn’t deter her. On the advice of her lawyer, she recruited the young laborers John O’Neil and John Smith and took possession of Tarpey’s cabin. Sarah, thirty-two-years old, stylish, and slender, was sitting there with O’Neil and Smith, unarmed, when Tarpey arrived on night of March 14. Tarpey shot into the cabin while Sarah and the men escaped out the back. The next morning, Sarah and O’Neil returned to the cabin. Tarpey emerged from the roadside with a loaded rifle. He claimed he fired at O’Neil in self-defense and Sarah got in the way. O’Neil, however, never fired his gun and claimed Tarpey shot Sarah intentionally. Regardless, Sarah took a full load in her torso and died.

In response, Melvin, who had been so opposed to Tarpey’s vigilanteism, became a vigilante. With his brother John’s help, he rounded up a crowd of 150 to 400 people. They disarmed and bound the sheriff, broke into the jail, and removed Tarpey. Outside, Tarpey’s wife and daughter clung to him while his mother and sister wept nearby. As the crowd took Tarpey away, the women followed, crying out in anguish. Melvin took Tarpey to the place where he had killed Sarah Nicholson. There, Tarpey was placed in a horse-drawn wagon with a noose tied around his neck. Melvin gave Tarpey time to declare his last will and testament and bid his farewells. Tarpey asserted his innocence and begged forgiveness. With the crowd gathered closely around so everyone would share the blame, Melvin and his collaborators startled the horse forward, and Tarpey was gone.

Tarpey was gone, but Dr. Cleveland and Tarpey’s other supporters remained. And so did fearless Melvin Jerome Gilkey… for now.

To be continued…

Read Part 5.

Read the entire series here.

Footnotes:

* At the same time, it was also considered to be in the county of Santa Cruz.

** Delightfully, it appears that a local woman, Charley Parkhurst (a.k.a Charles Darkey Parkhurst or One-Eyed Charlie), registered to vote in Santa Cruz County and participated in 1868 election, thereby becoming the first woman to vote in federal elections…fifty-two years before it was legal to do so. [https://gilroydispatch.com/charlie-parkhurst-casts-a-historic-vote/]

*** In 1873, the media (and public) sentiment was against Tarpey. Two decades later, however his role was romanticized and he was portrayed as a hero. Even his appearance was altered. From short, stout, and balding, he became a “bold, impulsive, dashing Irishman of splendid physique“ (Santa Cruz Sentinel, 12 Oct 1892, p. 2).

Sources:

Census records (Monterey County, CA; Santa Cruz County, CA)

Voter Registers (Monterey County, CA; Santa Cruz County, CA)

Books: Lang, H. 1882. A history of Tuolumne County, California : compiled from the most authentic records. San Francisco: B. F. Alley; Harrison, E. 1892. History of Santa Cruz County. San Francisco, Pacific Press Publishing Company.

Articles: Reader, P. 1995. “A Brief History of the Pajaro Property Protective Society: Vigilantism in the Pajaro Valley During 19th Century.” Santa Cruz: Cliffside Publishing.

Newspaper articles (Marin County Journal. “Murder and Lynching at Watsonville.” 20 March 1873, p. 2; Sacramento Daily Bee. “Murder Most Foul.” 15 March 1873, p. 2; Sacramento Daily Bee. “Matt Tarpey.” 21 March 1873, p. 2; Sacramento Daily Bee. “An Open Letter to His Excellency.” 23 April 1873, p. 2; Sacramento Daily Union. “The Lynching of Tarpey.” 19 March 1873, p.2; San Francisco Chronicle. “Tarpey Hanged.” 18 March 1873, p. 3 [an extensive account]; San Francisco Chronicle. “The Vendetta: A Brother of Matt Tarpey on the War Path. 25 March 1873, p. 2; The Daily Examiner [San Francisco]. “The Woman Murder—Etc.” 17 March 1873, p. 1 [includes Gilkey’s resolution]; The Daily Examiner [San Francisco]. “Woman Murdered; Lynch Law Probable.” 14 March 1873, p. 2; )