Part 5: In the Shadow of the Mountain. One man’s journey from a WWII incarceration camp to the second highest peak in California.

The Fishermen

Previously in this series, a discovery was made on a mountain, an immigrant started a family in California, that family’s world was turned upside down, and 10,000 people were incarcerated in the desert.

When Kazue Matsumura was a little girl at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, she sometimes sneaked out of the camp. Perhaps she was able to get out near Bairs Creek where the fence spanned a gully and it was easy to crawl under. She would go catch pollywogs in the stream or stick her bare feet in the water on a hot day or wander farther out from camp to look at the cattle ranging in the wind-swept desert chaparral. These were typical kid things to do.

“One time, the MPs came and said ‘You’re not supposed to be out here,’” she would later recall. “The military police who served as camp guards told Kazue and a friend she was with that they were going to take them to jail. The stern men loaded the little girls in their truck and took them to the camp police station. When Kazue thought back on the episode some 75 years later, she admitted they ‘didn’t put us in jail or anything. It was just to scare us.’”

Giichi Matsumura’s eight-year-old daughter was not the only person to ever sneak outside the camp. Other incarcerees would make their way beyond the barbed wire on occasions, if only to get a temporary respite from captivity and cherish a fleeting taste of freedom.

* * *

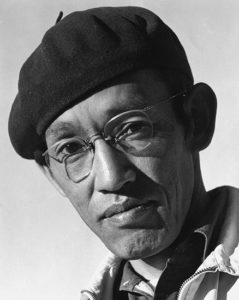

In 2004, Cory Shiozaki saw an article in the Los Angeles Times that featured a photograph by Toyo Miyatake. An award-winning professional photographer, Miyatake would later become best known for his photographs documenting the Japanese American internment at Manzanar. Using smuggled and makeshift equipment, he secretly took photographs at the camp while incarcerated there, often working during the early-morning hours to avoid detection by military police.

The Miyatake photo the Times ran was of a middle-aged man holding a rather impressive stringer of trout.

“The angler in this photograph,” the Times article explained, “has no smile and no first name known to us. He’s remembered only as Ishikawa, Fisherman — a sweet and haunting mystery from a dark chapter in U.S. history.”

Over the next several years, Shiozaki, a television cameraman and avid fisherman himself, would doggedly seek to solve that mystery. Through his research, he eventually learned the identity of that fisherman and the circumstances of how he and many others were able to pursue their cherished hobby.

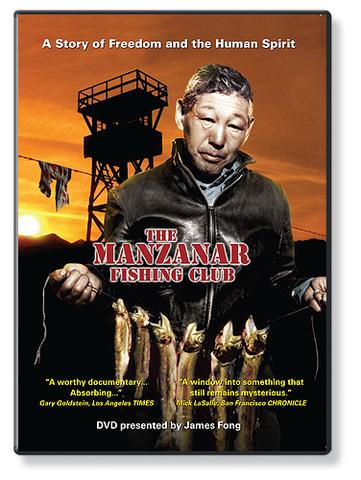

In 2012, the result of that research, The Manzanar Fishing Club, was released. The documentary film, directed by Cory Shiozaki and written by Richard Imamura, tells the story of several Manzanar incarcerees, including Heihachi Ishikawa (of that photograph), who would sneak out of camp to fish in the many nearby streams that flowed from the Sierra to the desert plains near Manzanar.

The documentary even highlighted excursions these intrepid men would make to backcountry lakes high in the Sierra, seeking the ever-elusive golden trout. One theme of the film was that fishing served as a symbol of freedom and even subversion for these men enduring forced incarceration.

* * *

In 1942, Jiro Matsuyama accidently discovered that Manzanar was part of eastern California’s bountiful fishing grounds. The 21-year-old defense industry worker had volunteered to come to Manzanar during construction of the camp, where he was asked if would like to work on the reservoir.

The water system being constructed at Manzanar consisted of a concrete dam and settling basin on Shepherd Creek, northwest of the camp. An open cement-lined flume carried water to another reservoir, and pipes fed storage tanks, ultimately leading to distribution lines into the camp. Maintenance and operation of the system involved having numerous men, including locals, volunteers, and eventually incarcerees, working outside of the camp boundaries.

When Matsuyama first went to check out where he might be assigned, he quickly saw something that caught his interest.

“When I saw the reservoir had trout in it, I said ‘That’s it, I’ll take it.”

The volunteer worker eventually became one of the 10,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated at the camp he helped to build and then one of the charter members of the Manzanar Fishing Club.

Another member of the water crew was Tom Ikkanda. His job required him to go outside the camp and check the streams, where he took notice of the abundant trout. He soon began bringing makeshift fishing gear with him to work.

“When I was out there fishing,” he later recalled, “you tend to forget everything that’s going on that is wrong.”

Soon word spread and many other men from the camp began surreptitiously fishing outside the camp, beyond the barbed wire. George Creek, Bairs Creek, and Shepherd Creek were the closest streams, and more were within hiking distance. Runoff from the nearby Sierra provided lots of water filled with lots of fish.

Security, however, was tight. Armed military police patrolled the fenced perimeter of the camp. Guard towers with armed sentries, machine guns, and powerful search lights augmented the harsh prison camp reality. The lure of “going fishing,” however, would not be deterred.

Industrious would-be anglers soon found ways to sneak out of the camp and avoid the searchlights. A gully where Bairs Creek crossed through the southwest corner of the camp provided space to pass under the barbed wire and shelter from visibility.

With fishing gear either fashioned from materials outside the camp or stowed hidden in pockets, men would head out in the pre-dawn hours and sometimes hike for hours to a secluded trout stream. At other times, water system workers or camp farmers would smuggle men out in work vehicles.

Sometimes getting back into camp with their catch was an even bigger challenge. And perhaps the most difficult thing to hide from the guards and MPs inside the camp was the smell of fish frying on make-shift kerosene stoves wafting through the barracks.

Eventually some of these Manzanar fishing enthusiasts made trips farther afield, even venturing into the High Sierra. Such excursions would sometimes last days, and getting away for extended periods of time was made easier by the general lessening of security at Manzanar during the later part of the its existence.

By 1945, the guard towers were no longer manned. The primary reason most people even remained at camp was that they had nowhere else to go. So much had been lost during forced evacuation three years earlier, and with no resources and no home to return to, Manzanar was the only place many had left to live.

While some hardy young men at Manzanar had ventured all the way into Williamson Bowl to fish the lakes behind the summit of the mighty Mount Williamson (14,379 feet elevation) that loomed over the desert plains of Manzanar, one incarceree had apparently ventured even deeper into the Sierra.

Trout experts claim that the stringer of trout Heihachi Ishikawa was holding in that Miyatake photo were golden trout. While similar to fish found in the lakes of Williamson Bowl, this particular species of trout were only found in more distant areas of the Sierra. Ishikawa, a weathered, albeit hardy man in his 50s, would ramble through the Sierra for weeks at a time.

It is unknown how far he went to find those goldens, as he generally ventured out alone. As a fisherman, he was in many ways legendary, Miyatake’s photo only cementing that status.

In late July 1945, several other (much younger) fisherman from Manzanar, knowing the war was winding down, wanted to take one last fishing trip. Perhaps they knew of Ishikawa’s catch and wanted to find some goldens themselves. Maybe they saw this as their last chance. It was increasingly evident they wouldn’t be at Manzanar much longer.

Amos Hashimoto, who had lived in the Japanese fishing village at Terminal Island before the war, was organizing the trip. One man, who worked on the water system and thus probably knew many of the fishermen, was a 46-year-old incarceree who wanted to go on this trip up to the mountains.

Giichi Matsumura was not so much interested in fishing as he was in painting. He was looking for new and dramatic landscapes to serve as subject matter for his watercolor paintings.

Hashimoto tried to dissuade Giichi from coming along. The hike would be grueling. They would be climbing up over 12,000-foot Shepherd’s Pass. The bowl where the lakes were was a brutal scramble of jagged rock.

Giichi, however, was persistent. He really wanted to go. Perhaps he even pointed out that he wasn’t as old as Heihachi Ishikawa, and he’d been all over those mountains.

The group of anglers relented. Giichi could join them. He would have a chance to paint Mount Williamson from an entirely different vantage point. He would be in the shadow (on the other side) of the mountain.

* * *

In a 2018 oral history interview conducted by Rose Masters, an interpretive ranger at the Manzanar Historic Site, Kazue Matsumura, then well into her 80s, admitted that she had always had premonitions.

“I get those feelings sometimes, you know, before…”

She remembered that back in the summer of 1945, when she was only 10 years old, she had a very bad feeling about a trip her dad was about to take.

In next week’s final installment of In the Shadow of the Mountain, Giichi makes it to Williamson Bowl, World War II draws to a conclusion, and life is once more turned upside down for the Matsumura family.

Click here to purchase The Manzanar Fishing Club DVD from the Japanese American National Museum.

Read Part 6.

Read the entire series here.