Part Five: The Double Murder

By Laile Di Silvestro. Published March 2025.

This is Part Five of a multi-part series by historical archaeologist Laile Di Silvestro. The series started with an astonishingly bold act—two women staking a claim in the remote Mineral King Mining District in what is now Sequoia National Park. The tale unfolds in California in the second half of the 19th century. It was place and time where women struggled to thrive within power structures that favored unscrupulous men. It is a true story. Read Part Four HERE.

A corrupt coroner can help men and women get away with murder.

Are you perhaps a wee bit trigger-happy after tipping the bottle? Fear not if you have your county coroner in your pocket. He can simply declare the cause of death something other than homicide. Or, the coroner can handpick a small jury to assist in his inquest, and the jurors will deem someone else more worthy of a full trial… or a lynching.

Take, for example, the ghost story in Part 3. It was a coroner’s jury that decided it was Jim Lyons rather than the small statured lawyer who had killed John Blakely, despite a complete lack of evidence.

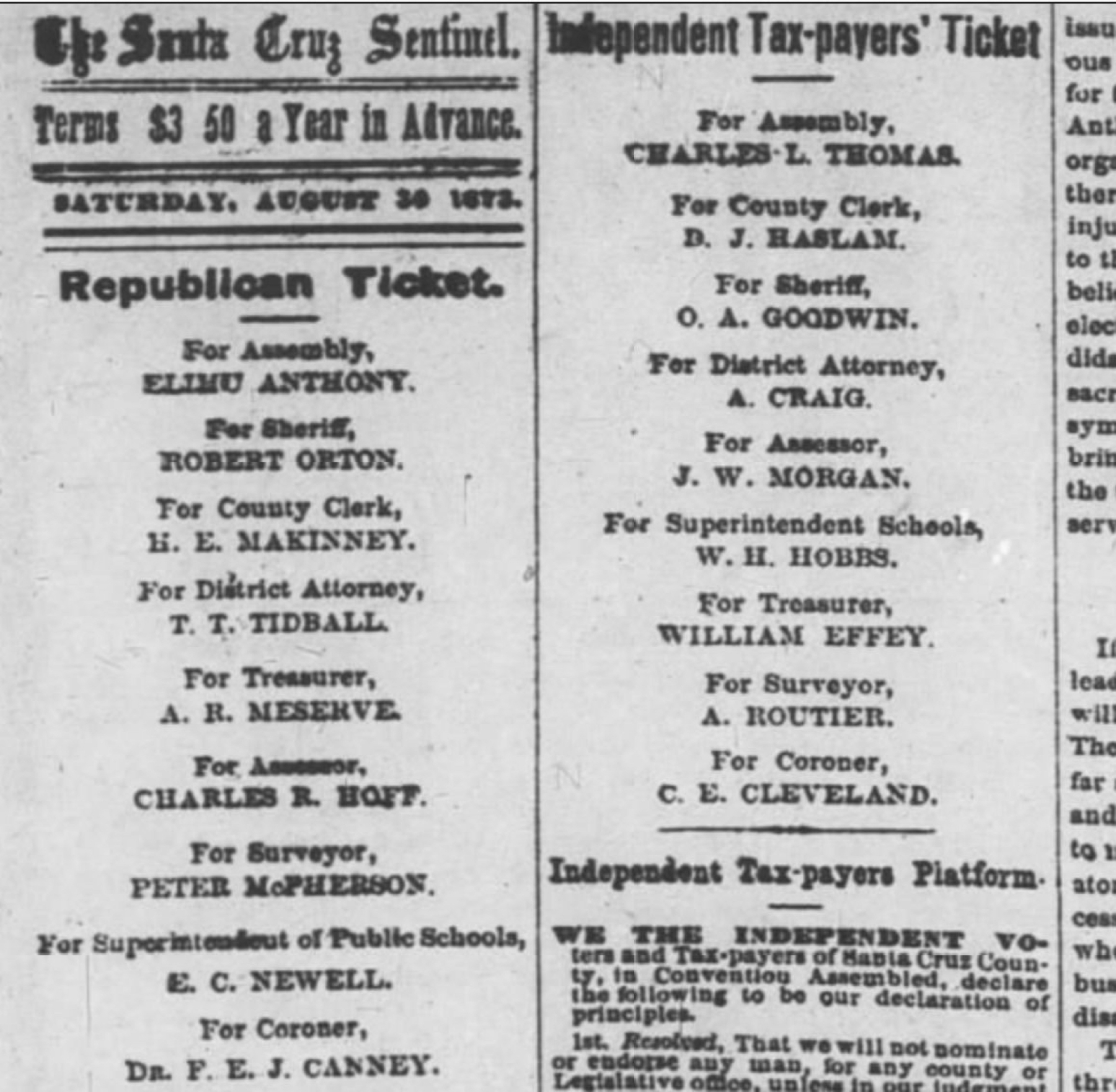

Within this context, it may not surprise you that Melvin Jerome Gilkey’s sworn enemy was Dr. Chester Edwin Cleveland—the Santa Cruz County coroner during vigilante Matt Tarpey’s reign of terror.

According to all accounts, the two men had hated and threatened to kill each other for years. The seed of the feud is unknown; however, by early 1874 both men were ready to finish it.

The doctor was living alone at this point, drinking away his income. His oldest daughter was married, and his wife and other two children were dead. He was having a difficult time competing with the town’s other physician. Indeed, Chester was so unpopular in his own town of Watsonville that, although he won the countywide election for coroner in 1869, only 46% of the Watsonville electorate voted for him.

Chester’s strong support for Tarpey could not have helped his popularity. As Chairman of the County Central Democratic Committee, he had embraced the vigilante society, and as coroner, he had helped Tarpey and his fellow vigilantes escape prosecution for the lynchings.

After Tarpey’s lynching in March 1873, the town’s Democratic leadership (presumably including Chester) sent a letter to the state governor asking that Melvin and his collaborators be brought to justice, to no avail. Chester ran for county coroner again in November, and lost resoundingly.

Melvin was having his own problems. His wife had died in 1868, and he had a seventeen-year-old daughter and sixteen-year-old son. He had escaped prosecution for Tarpey’s lynching; however, he had recently been arrested and examined for raping his own daughter. His son was soon to be arrested for rape, as well.

Chester lit the final spark by testifying against Melvin in the rape case. Now all that was needed was some combustible liquid.

On Saturday February 21, Melvin came into town in a quarrelsome mood. He spent the day drinking and arguing and was heard to say he was going to kill Chester. At about midnight, Chester declared his intention to kill Melvin, but said he needed to fortify himself with whiskey first. He entered the Tom Scott Saloon, where Melvin was drinking. The two men ignored each other while Chester downed shots of whiskey, then Chester left the saloon. He had made it only to the other side of the street when he declared he needed another shot and returned to the Tom Scott. Again, the two men ignored each other and Chester left. This time Melvin followed him out.

“There’s the [censored expletive] now!” Chester exclaimed.

Melvin approached fearlessly.

“You [censored expletive], I am prepared for you,” said Melvin.

They walked towards each other and drew their guns. They stopped when they were about two feet apart.

They held their guns almost muzzle to muzzle, each one pointing at the other one’s chest. There was no chance either one would miss. And they didn’t.

The women of Watsonville spent Sunday afternoon visiting the saloons and convinced them all of them to close until the men’s bodies were interred less than 24 hours later. When the saloons reopened immediately after the funeral, business was brisk.

Meanwhile, a coroner’s jury briefly met over Melvin’s body from which someone had pilfered his watch and $20. They deemed the deaths a double murder.

To be continued…

Read Part 6.

Read the entire series here.

Sources:

Census records (Monterey County, CA; Santa Cruz County, CA)

Books: Lang, H. 1882. A history of Tuolumne County, California : compiled from the most authentic records. San Francisco: B. F. Alley.

Newspaper articles (The Santa Cruz Sentinel. “Official Election Returns.” 11 Sep 1869, p. 2; The Santa Cruz Sentinel. “Santa Cruz County Democratic Convention.” 22 Jul 1871, p. 3; The Santa Cruz Sentinel. “Election Returns.” 13 Sep 1873, p. 2; The Daily Examiner [San Francisco]. “Bloody Tragedy at Watsonville.” 23 Feb 1874, p. 3; The Santa Cruz Sentinel. “A Bloody Deed: Shocking Tragedy in the Streets of Watsonville.” 28 Feb 1874, p. 1; The Santa Cruz Sentinel. “Watsonville: The Sunday Tragedy: ” 28 Feb 1874, p. 2; Evening Express [Los Angeles]. 18 Mar 1874, p. 3.