A History of the Kaweah Colony: The Milling Begins

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published August 2020.

Our First Lumber

Tis but a chip of pine

Picked from a rough sawn board,

Yet many a chip of pine

A story may afford

(The Kaweah Commonwealth, July 26, 1890)

Early in the summer of 1890, the Colony road had reached the pines after nearly four years of grueling work. The heavily timbered land that had long been considered inaccessible was now reachable on an impressive wagon road nearly 20 miles in length that climbed over 5,000 vertical feet. It had been made possible not by huge expenditures of capital, but by the cooperative sweat and labor of Colony members who toiled not for mere wages, but for the common good of the community they had joined. Of course, many had paid dearly to join that community, and continued to pay if not with cold hard cash then with the sweat of their brow. Still, those who joined had nearly all done so believing their cooperative resources would pay dividends to them all.

With the road complete into the timber belt, their most valuable resource was finally accessible. However, there was still much work to be done. A workable mill had to be established, which required equipment and still more labor. Only then could the felling, milling, and transporting of lumber begin, which called for more equipment and some fairly specialized and skilled labor. The Kaweah Colony was fortunate, however, that certain members happened along when they did. Irvin Barnard was one such member.

BARNARD AND HIS AJAX TRACTOR

Irvin Barnard had been a farmer in the coastal town of Ventura, California, before joining the Kaweah Colony. With his arrival as a resident member in 1890, the Colony gained some important assets. For one thing Barnard had considerable capital at hand, for it was he who acquired the lease on a sizable tract of land in the lower North Fork canyon that would eventually become Kaweah Townsite.

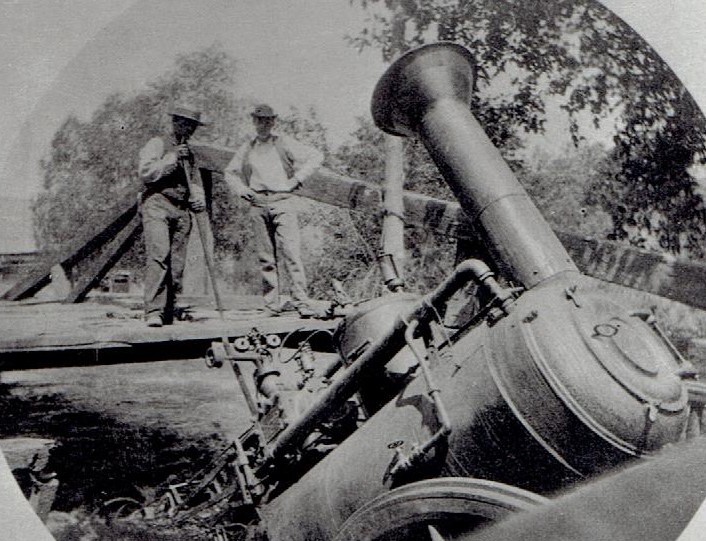

He also brought to the Colony a much needed Ajax steam traction engine, which was just the thing needed to power the sawmill they were establishing at the end of the road. Ajax traction engines were sold by A.B. Farquhar of York, Pennsylvania, a manufacturer of farm and sawmill equipment. According to the 1887-1888 catalogue, there were four sizes of Ajax engines — from 8 to 14 horsepower — costing in the range of $1,175 up to $1,625. The number two engine, for instance, was a 10 h.p. unit that would use about 400 pounds of coal and 10 to 12 barrels of water in a day’s operation. It had a 6½-inch diameter cylinder with a 9-inch stroke and operated at 275 rpm. Although these traction engines were equipped with steering gear and could be driven under their own power, they were also supplied with a removable tongue so that when used on a road a team could be used for steering. In this way these portable engines could be pulled by team from job to job.

Getting Barnard’s Ajax to the job site at the end of the Colony’s road to the pines proved to be a considerable and eventful task. It is unclear how Barnard transported the engine the 200 miles from Ventura to Visalia. Freightage via the railroads would have been costly and driving it or pulling by team all that distance an ambitious and time-consuming trip, but Barnard was apparently a man of both means and ambition. In any event, the journey was without mishap until reaching the foothills and a bridge across the South Fork of the Kaweah in the village of Three Rivers, a few miles from the Colony grounds.

Crossing on an old and infirm wooden bridge, the eight-ton Ajax, along with its driver, crashed through into the rushing stream below. The South Fork is not a large tributary — it is the smallest of all of the Kaweah’s forks — so this bridge was low and the fall neither great nor fatal. Barnard suffered only a few bruises, but his vest and a gold watch were swept away in the current and never recovered. The Ajax, fortunately, was recovered. With a great deal of labor and a bit of ingenuity, the huge tractor was pulled out of the stream bed and tangled rubble from the collapsed bridge. Soon, however, Barnard faced the even greater task of crossing the much larger Middle Fork.

Swollen from a heavy spring runoff, the main Middle Fork of the Kaweah had recently taken its toll on a ferry built by the Colony, destroying it against the rocks. When Barnard arrived at the crossing, there was no way to cross, and he suddenly found himself not only stuck on the wrong side of the river, but in the middle of a Colony debate over building either another ferry or a bridge. The ensuing dispute was a prime example of the frustration Colony leaders often faced.

Barnard returned to Visalia, where he brought news of the ferry’s demise and the current situation to Colony Secretary James Martin. In addition to needing to get the Ajax across, the Colony faced a much more urgent need of getting supplies across to a suddenly isolated settlement. With the deep snows in the Sierra that year, the swift-running torrent would likely continue for some time. It would be several weeks before the main fork could safely be forded. A way across was of paramount importance. Martin later recalled that “a short talk with Mr. Barnard convinced me that he was the very man needed to meet the situation.”

Barnard had experience with ferries; he told Martin it was the most practical, least expensive and quickest way of re-establishing connections to the cut-off Colony. He outlined exactly what materials were needed. It was obvious to Martin, a trustee of the Colony, that an immediate decision was needed and in less than two days the materials arrived at the spot on the river where the new ferry would be built. Martin’s unpublished history of the Colony continues the story as he remembered it. He wrote:

In the meantime at the Colony there had been, naturally, much talk with regard to the situation and what was to be done. When the material for a new ferry arrived it appeared to be a shock to a few ardent democrats that a matter of such importance had not been discussed at a special meeting. One member, who assumed to be more or less of an engineer, had induced a few to believe that a suspension bridge could be built of the worn-out wire cables discarded by the street cars in San Francisco, which he thought could be obtained for the proverbial song. It was rather a wild suggestion, but it took with a few because of the idea of economy. They failed to recognize that the hauling and freight on the amount to build a suspension bridge that would stand the strain of four horses and a loaded wagon would amount to much more than the cost of a new ferry. Nor did it occur to them that a bridge built of worn-out cable did not commend itself on the score of safety. And besides, a ferry would have to be built to bring across the river the material necessary for the construction of the tower to carry the cable across, and for supplies to the Colony while the bridge was being built.

There were, perhaps, twenty advocates of the suspension bridge idea who would have liked to take a day or two off to thrash the matter out in a meeting, but when the material arrived on the opposite bank for the ferry the question was settled. Argument was then changed to criticism. It was contended that a ferry was unsafe, and besides, what did Barnard know about ferry construction anyway? Barnard’s reply to this was that he had quite recently fallen through a county bridge with his tractor and that fact had not tended to increase his affection for bridges, especially suspension bridges of amateur construction. “But,” he said, “if it will afford comfort and relief to the timid, my tractor and myself shall be the first to cross on the new ferry; I will drive onto the ferry with a full head of steam and toot the whistle vigorously while crossing.” This was regarded as fool-hardiness by the bridge advocates. The time was set for the crossing, and a small crowd assembled, some of whom rather expected to witness a tragedy. Barnard, however, made the crossing in safety while the echoes rang with a multiplicity of toots.

On June 21, 1890, the Colony newspaper, which had been following the progress of the Ajax, proclaimed, “All engine difficulties are past. The whistle of the engine has been heard at Advance.” The report added that it would remain there “until the return of Comrade Barnard, who will take his son up to the mill site with him and probably leave him in charge of the mill.”

CAULDWELL’S RETURN

When Special Land Agent Andrew Cauldwell filed his investigative report on the Colony in July 1890, his involvement with the case was seemingly over. While the report was generally favorable toward the colonists, he had questioned the legality of the individual claimant’s quitclaim deeds to the Colony. While satisfied that the original intent of the entrymen was to “place their claims in a common pool after they had proved up and paid for their claims, to be worked co-operatively for their joint benefit,” the withdrawal of the land and suspension of the claims changed matters.

Cauldwell’s report explained how Colony leaders nonetheless “instituted and partially carried out the plan of getting quit claim deeds from filers.”

I am satisfied [Cauldwell wrote] that nearly all of those timber entrymen who made these quit claims did so through a misinterpretation of the law, their attorney [Haskell] having advised them that having once tendered their final proof and money in payment they could subsequently deed their equity in the claims to the Colony Company, notwithstanding the fact that the Land Office had refused to receive their proof and money.

His ultimate recommendation was to cancel all the timber claims in the suspended townships without prejudice to any individual claimant “to the end that such as honestly intended to enter said timber lands for their own use and benefit can have an opportunity to make new filings thereon whenever the suspension is removed,” thus opening the door for anyone, be they Colony member or otherwise, to make brand new claims.

This recommendation was never heeded, and a growing conservation movement undoubtedly influenced the decision. In fact, with bills already introduced in Congress to preserve California forest land, Secretary of the Interior John Noble, who was in favor of the movement, ordered the commissioner of the Government Land Office to renew suspensions on the townships containing sequoia trees until a complete report could be rendered concerning the location of the Big Trees. Cauldwell, a temporary employee of the Interior Department, was already familiar with the area and drew the assignment. It probably helped that the congressman for the district and author of two bills to set aside forest reserves, William Vandever, had personally written the Secretary of the Interior asking that Cauldwell be given a permanent appointment, citing the character of his work as evidence of his efficiency and fidelity. Cauldwell returned in August to make a comprehensive report on the location, number, and size of giant sequoias in and around the Giant Forest. This new assignment also marked a dramatic shift in Cauldwell’s attitude toward, and relationship with, the Kaweah Colony.

By August, Barnard’s Ajax had made its way up the Colony road to the timber, and a sawmill had been erected. Production that first summer did not, however, live up to expectations. Burnette Haskell later vented his frustrations concerning the mill’s output when he wrote:

A total of 20,000 feet (at $10 per thousand) was cut during a three month’s run with a mill whose capacity was 3,000 feet a day; the actual cut average 193 feet per day; less than a tenth of what ought to be done, and this mill was not run short-handed. It is true that most of the time it did not run; that loggers were inexpert; that the mill was small and old; that picnics had to be organized; that the men had to come down for “General Meetings,” that this foreman was bad and that foreman was worse; that the timber was small; that the oxen were lame, and a hundred other reasons, but the fact remains that results were not attained.

Haskell was obviously bitter when he wrote this, but even the ceaselessly optimistic Commonwealth hinted at problems at the mill that summer. “Work at the sawmill is progressing fairly this week, considering the lack of help,” they reported, exhibiting a rare instance of qualified negativity. “Comrades Barnard and Shaw have worked like Trojans to prepare the new edger for service. A fine new belt has also been put up, and several other improvements made which will add materially to the capacity of the mill.”

The Commonwealth later tried to put a positive spin on another unforeseen setback. “The oxen recently purchased,” the paper noted, “are recovering strength and flesh in the pines. The exception is one of the weakest, whose neck was broken while grazing too close to a rocky bank.” Nonetheless, logging had begun and the Colony was finally producing lumber — the valuable and vast resource that would sustain their cooperative dream.

Cauldwell was well aware that the land upon which the colonists logged had not been patented nor deeded to them. It was still technically public land, and he was compelled to warn them against cutting timber upon it, insisting they desist at once. He had personally caught them in the act of “timber trespass” — cutting trees on public land — and at once reported the infraction to the Department of the Interior on August 15, 1890. This, however, was one fact that had no detrimental effect on production at the mill, for the warning was patently ignored. One can easily imagine the negative effect this had on Cauldwell’s relationship with the Colony. Tensions between them grew.

CONSERVATION SUCCESSES

Meanwhile, it should be remembered that Vandever had introduced his bill calling for the reservation of the Garfield Grove area and that it was successfully speeding through Congress. On September 11, 1890, the Visalia Delta, in reporting the rapid progression of Vandever’s Sequoia bill, commented that:

In these days of tardy legislation, it seems wonderful that this bill should be introduced in Congress and passed without opposition, and then taken to the Senate where it is favorably reported by the committee on public lands, then presented to the assembly and passed without debate. The bill will be presented to President Harrison to sign and there is not the least doubt but that our chief magistrate will affix the seal of his approval to the measure. Those who have taken an interest in the successful passage of the bill can well congratulate themselves with their splendid work.

Even The Kaweah Commonwealth saw the rapid passage of the bill, which it must be remembered reserved the Garfield Grove area many miles south of all the Colony claims, as good news. With its passage imminent, they proclaimed that “never were the prospects of Kaweah more bright than today!” and went on to explain that “this news assures the retention of our rights to the Giant Forest, as one National Park is all that is likely to be created for some time to come in this vicinity.” In other words, the Colony cheered the creation of a park reserve as outlined in Vandever’s bill because it didn’t encompass their land. They had dodged the bullet of legislated conservation.

THE YOSEMITE BILL BOMBSHELL

Introduced months before the Sequoia bill, the proposed legislation to create a federal reserve around the state-controlled Yosemite had come about in great part due to the agitation of John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine. Envisioned by Muir to protect the vast watersheds surrounding the Yosemite Valley, which was already protected by the State of California, the bill was introduced in March 1890 by Representative Vandever.

Johnson had a great deal of influence in Washington, and even after the bill had been introduced he worked hard to convince the House Committee on Public Lands that it did not go far enough. Armed with a statement and a map from John Muir, who urged that the Yosemite Reservation ought to include the Tuolumne River watershed and the Ritter Range to the east, Johnson lobbied for extension of the boundaries of the proposed reservation. He appeared before the Committee on Public Lands on June 2, 1890, and finally by late September achieved positive results. A second Yosemite bill was substituted and passed through both houses of Congress on September 30, the last day of the session, without the customary bill printing. This new bill provided for a park that was almost township for township like the one Muir had sketched for Johnson. The substitute bill, which became law on October 1, 1890, created a park more than five times the size of the one originally proposed by Vandever. Yosemite became the second national park created in California in less than one week.

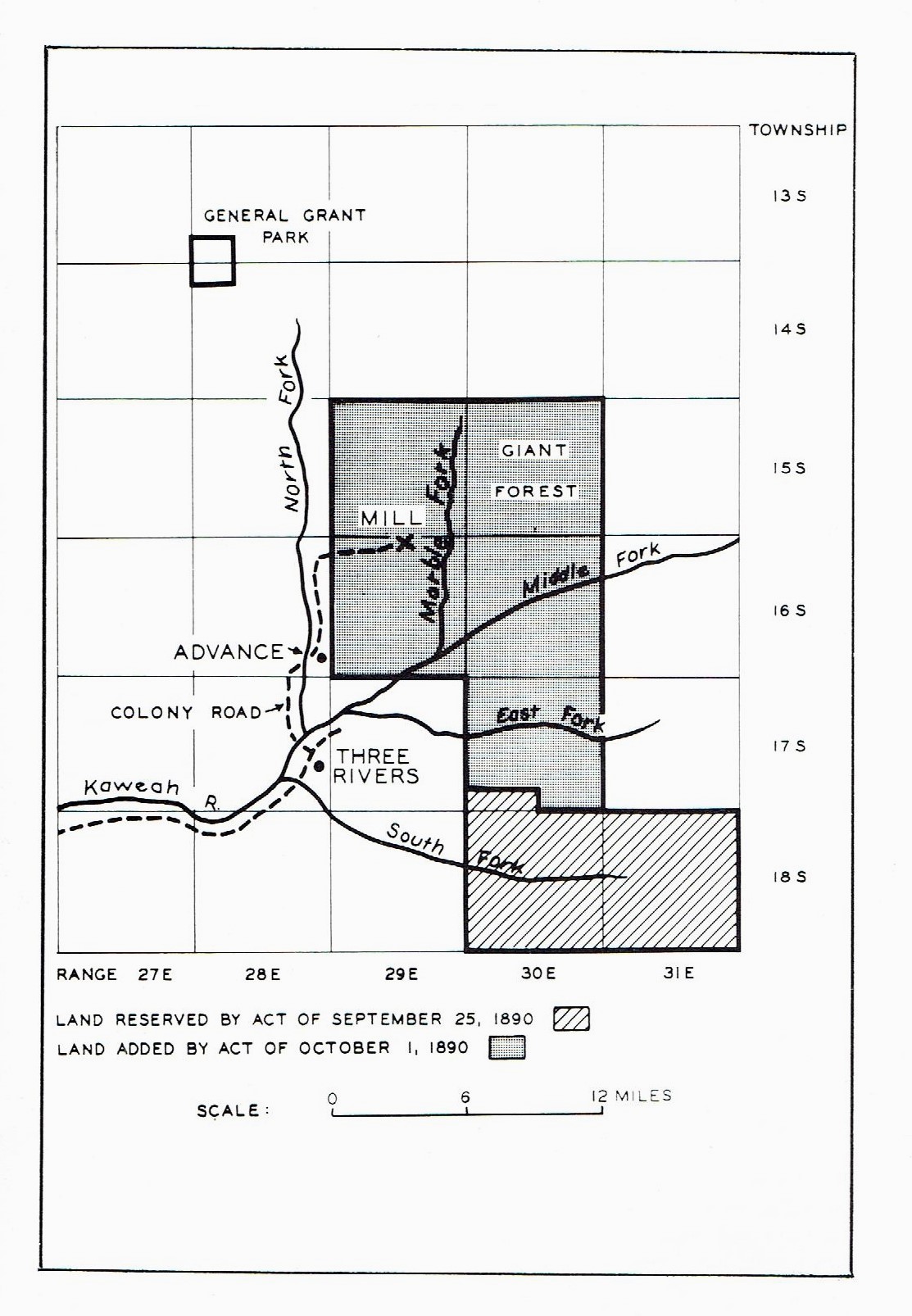

The substitute Yosemite bill, introduced in the eleventh hour and rushed into law, created not only a vastly enlarged Yosemite National Park, but with its added sections of text created General Grant National Park and added four townships to the newly created Sequoia National Park.

Section Three of the Yosemite bill, which added to Sequoia National Park an area more than twice that which had so recently been reserved, described the addition only by township, section, and range numbers, so it was unlikely that any of the politicians who passed this bill realized that the area added included the famed Giant Forest and all of the Kaweah Colony timber claims. Nowhere in the text was there any mention of the Sequoia bill passed only a week earlier, nor of the famed Giant Forest, Tulare County, and the Kaweah watershed. With a road newly completed to the timber belt and claims filed on much of the land in question, it would have been hard to label this added land as worthless, which had historically been (and would continue to be) a key factor for consideration of reserving public lands.

Assured by the Committee that it was not “proposed in any manner to interfere with the rights of settlers or claimants,” the bill was read and passed through the House without any debate. In the Senate, the bill was read, and Senator George Edmunds of Vermont complained that it could not be understood and should be printed. Then someone spoke quietly to Edmunds, and he withdrew his objections. The bill passed the Senate without further debate. The one thing these congressmen did understand was that forest preservation had become a popular stance, so with the session nearly over, it is hardly surprising that they took the opportunity to cast their votes to save the Sierra forests.

The establishment of two national parks (and the mysterious enlargement of one) marked the end of the summer of 1890, a time of incredible activity and optimism for the Kaweah Colony. Several elements of Kaweah’s story progressed at once during that exciting spring and summer: the road was finished and a sawmill erected; a community began to flourish at Advance; a Nationalist movement gained momentum and helped attract members to the utopian endeavor; a growing conservation movement took root and began to realize legislative success; a government Land Agent investigated, supported, and ultimately antagonized the Colony; and the driving force behind Kaweah — Burnette Haskell — finally focused his commitment solely on the Colony, moving his family to the Sierra settlement. As summer gave way to fall, all these divergent aspects converged at one place and time. In fact, Haskell and his wife, Annie, arrived at the Colony on the very day the Yosemite bill was signed into law.

It was several weeks before news of the bill’s passage and the enlargement of Sequoia National Park reached California. It would be decades before the mystery surrounding this development came to light.

SOURCES: In addition to contemporary newspaper reports in The Kaweah Commonwealth and the Visalia Weekly Delta, and books such as Dilsaver and Tweed’s Challenge of the Big Trees and John Muir and the Sierra Club Battle for Yosemite by Holway R. Jones (Berkeley, Calif., 1965), other sources for this chapter include “Kaweah Colony Traction Engine” in Los Tulares (No. 31, June 1957), Haskell’s article on Kaweah from Out West magazine, and James J. Martin’s unpublished manuscript “History of the Kaweah Colony” (including drafts and notes, circa 1930, Martin Family papers, Bancroft Library).