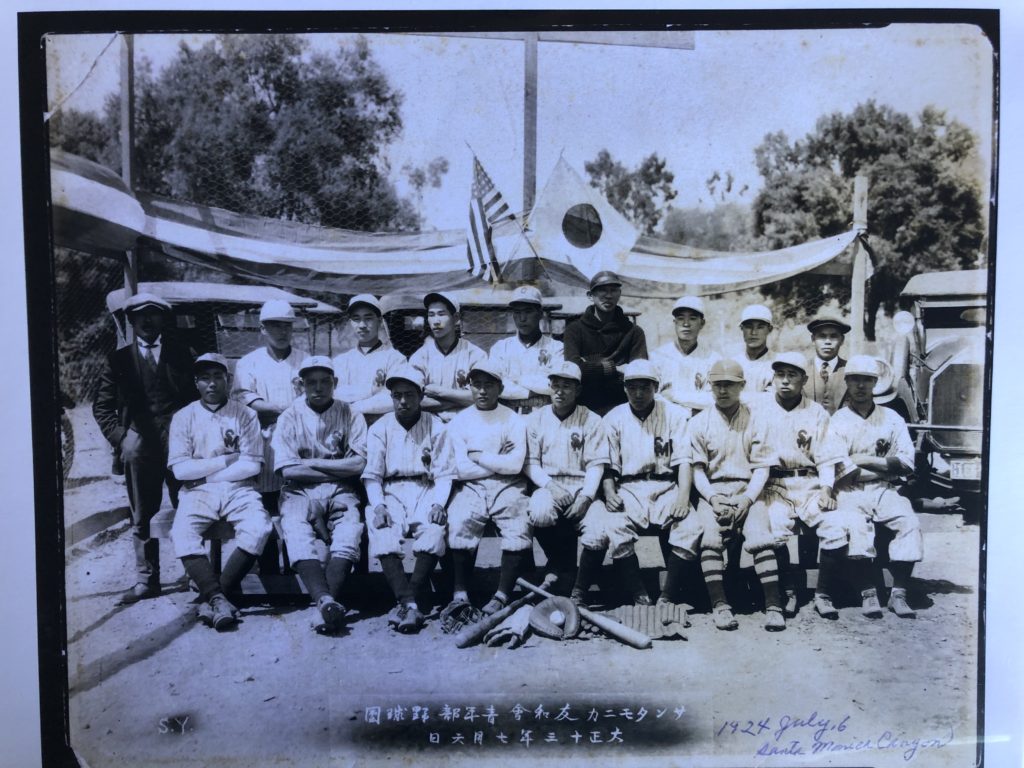

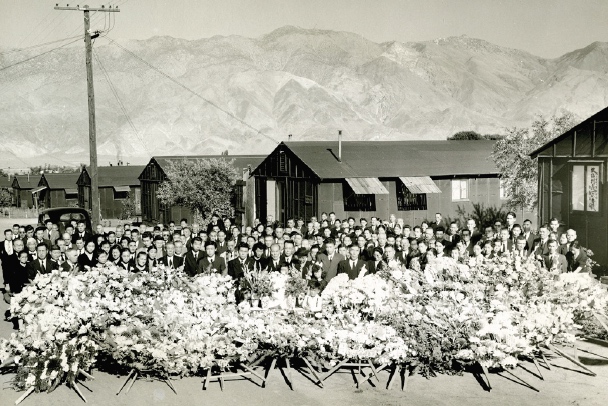

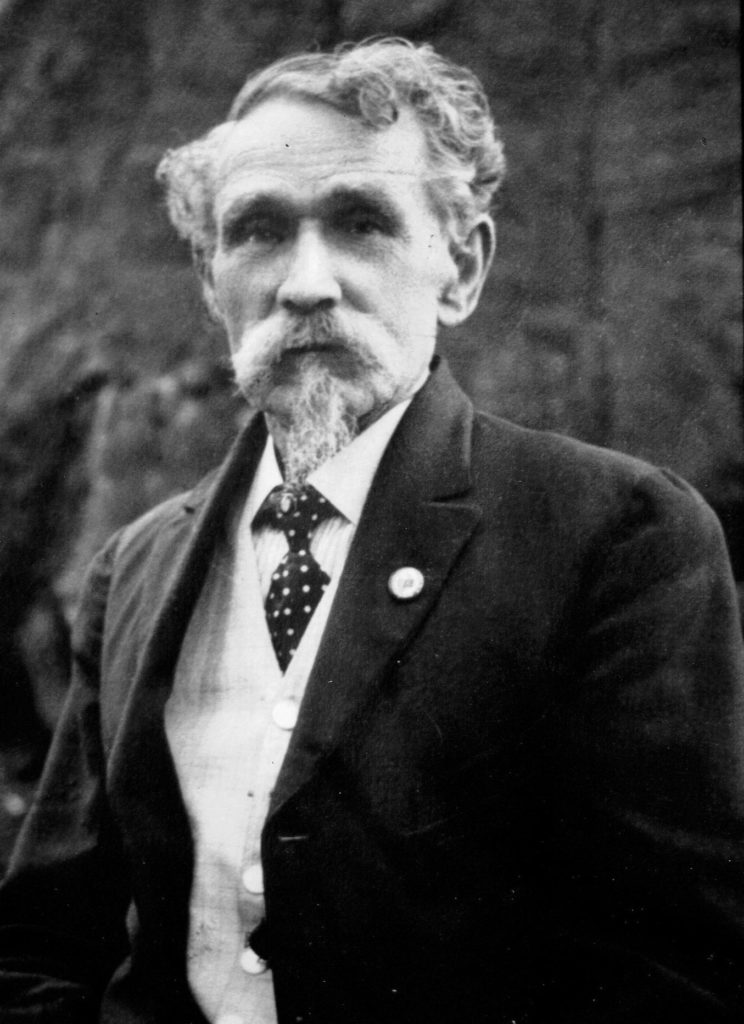

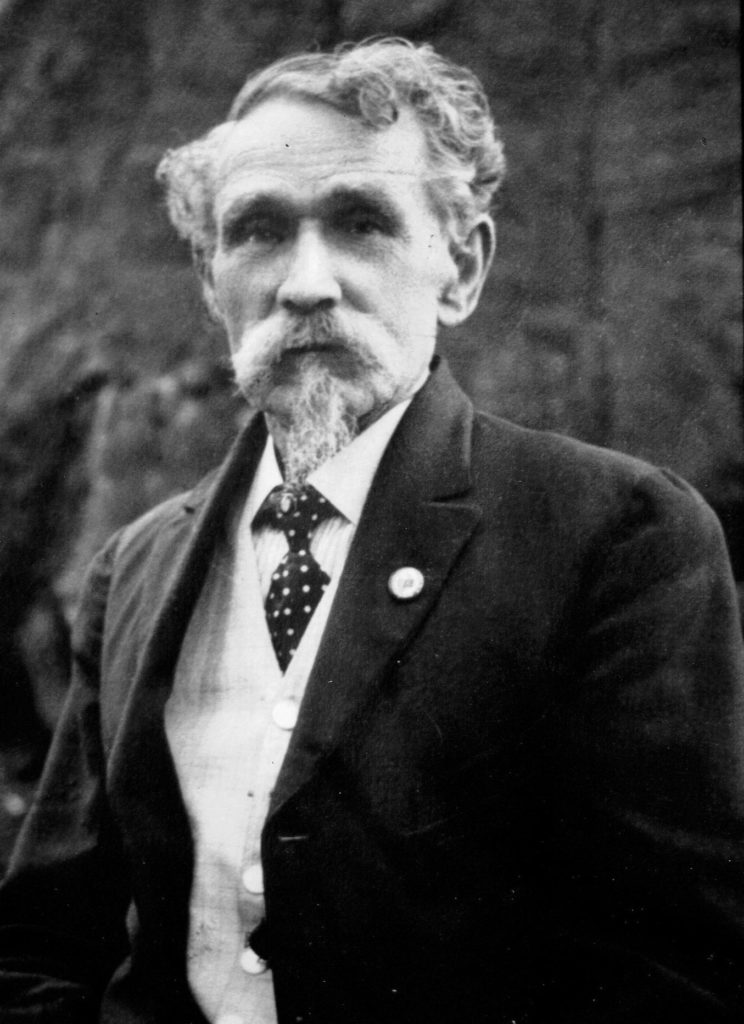

Having occasion to take a train down the valley I was fortunate to find a seat… behind two men who were civil engineers.[One] informed his companion that east of Visalia was the most magnificent forest in the state of giant redwoods [which had] lately been opened for sale. That revelation seemed to me a pointer by God himself… and a beginning of the scheme I had in mind.(Charles Keller, in photo above)

The story of California can be told in terms of land. So stated historian and former title insurance executive W.W. Robinson in his book Land in California. “Better still,” he continued, “it can be told in terms of men and women claiming the land.” One man who lived that story was Charles F. Keller.

In the spring of 1885, Charles Keller, a resolute looking man with a small beard, neatly trimmed to form a point at the chin, was 39 years of age. Born in Germany in 1846, he had come to America with his parents when he was a boy of nine. They had settled in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, along the Susquehanna River.

In 1864, he ran away from home to enlist in the 7th U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, serving for the remainder of the Civil War. Keller came west to California in 1867, arriving first in San Francisco. The 21-year-old was not much impressed with the town and before long had signed on with a work party that took him down to the southern part of the state, to the San Bernardino Mountains. There Keller worked building a mill and dam for a mining operation. The pay was excellent — five dollars a day in gold plus board — but the job only lasted six months. Keller and California Land

The next stop for Keller was in the valley below, in the town of San Bernardino, where a short stint in the brewery business ended after a flood inundated his adobe brick beer cellar. Keller found himself on the move again, and he would be many times before settling in the booming San Joaquin Valley town of Traver, which is where he was headed on a spring day in 1885.

BOOMTOWN OF TRAVER

If the story of California is to be told in terms of land, then that story is never really complete until water is added. While the politics of water had yet to dominate California as it did after the turn of the 20th century with the eras of the Reclamation Board, William Mulholland, and the Central Valley Project, water was beginning to permeate every aspect of California’s development by the 1880s.

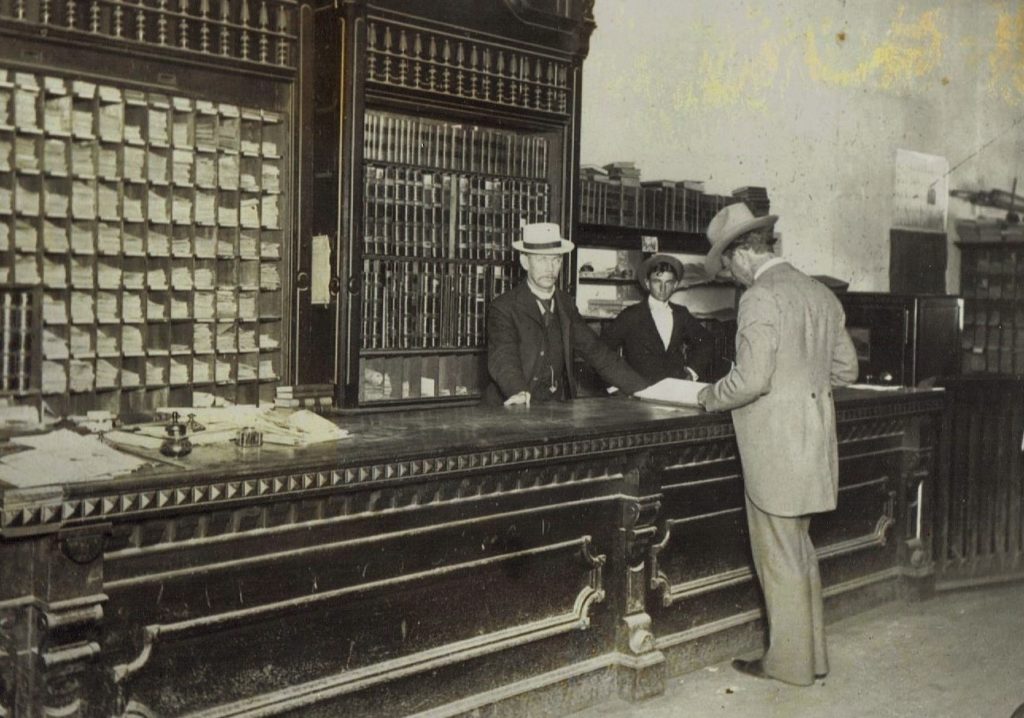

It was water, rather than gold or silver, that fueled the boom in Traver, and Charles Keller had been enthusiastically attracted to the opportunity the blossoming town offered. Situated only 10 miles north of Visalia, the county seat of Tulare, Traver was a product of one of the first large irrigation projects in the Central Valley. The 76 Land & Water Company was formed in 1882, conceived by civil engineer P.Y. Baker. With the aid of several investors, the project set out to develop thousands of acres of land by means of irrigation.

While California’s great Central Valley was mostly arid in terms of rainfall, there was a bountiful water source nearby. The valley is bordered on both the east and west by mountains, and those to the east comprise one of the largest, most spectacular mountain ranges in the world. When the earliest Spanish missionaries first viewed the range from afar, they described it as “una gran sierra nevada” — literally, a great snow-covered range — and the name stuck.

Several major river systems carry the runoff of the Sierra Nevada into the Central Valley. Those rivers draining the watersheds of the northern and central Sierra ultimately flow into the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, which form a complex delta system and eventually meander into the San Francisco Bay. The southern, and steeper, end of the Sierra is drained on the west by three major streams — the Kings, Kaweah, and Kern rivers — all of which terminate in the southern San Joaquin Valley. The waters of the Kings and Kaweah once drained into the vast Tulare Lake. (The lake is now usually dry, but prior to the advent of extensive agriculture in the valley, it was the largest body of water west of the Mississippi and boasted perhaps the greatest concentration of game and fish anywhere in America.)

When irrigation projects moved this bountiful water to otherwise arid land, large districts that had afforded nothing more than sheep ranges would be converted into lush gardens, vineyards, orchards, and alfalfa pastures, the irrigation promoters promised.

Irrigation certainly was not a new idea to the San Joaquin Valley in the 1880s, although there were still those opponents who claimed irrigation on such a large scale would be disastrous. Skeptics and naysayers feared that the action of the water under the influence of the sun would destroy the substance of the soil, or believed that when the water was put upon the land it would produce chills and fever in such amount that irrigated districts would be uninhabitable.

But by the mid-1880s, local farmers were familiar enough with small-scale irrigation, and investors so motivated by the economic potential, they paid little if any heed to such dire predictions. With water assured for the district, promotion was started on a grand scale early in 1884.

The final step for the 76 Land & Water Company called for the establishment of a town, which was named for one of its directors, Charles Traver. Within one month, Traver could boast of three mercantile stores, two lumber yards, two livery stables, a post office, two hotels, barber shops, and a new railway station in the process of being built. Schools and churches soon followed, and the town, situated on the main Southern Pacific line, quickly became the principal shipping point for grain in the area.

While nearby Visalia was a fairly sizable and well-established town, having been around for several decades rather than a few short months, Traver had become the rising star in the Central Valley. Charles Keller undoubtedly felt like finally, for once in his life, he was at the right place at the right time. He would finally obtain a piece of the golden opportunity the California dream had always promised, but which so few had realized.

BONANZA WHEAT FARMS

As Charles Keller rode the train through the Central Valley that spring day in 1885, the landscape outside his window was dominated by endless acres of wheat — it was the era of the bonanza wheat farms. Grain farming was one of the first agricultural enterprises in the Central Valley. It could be successfully dry-farmed most seasons, and the coming of the railroad in 1872 provided a boon, opening up vast markets. Additionally, California wheat was able to withstand long shipment by boat, thus opening up the European market.

Not really farming at all, but more like a variety of mining — exploitative farmers would decimate the soil, planting the fields year after year without variation of crops, giving the land neither rest nor manure. Once a section was exhausted they would simply move onto virgin soil elsewhere on their vast landholdings. The same feverish frenzy that characterized mining in Gold Rush California also characterized wheat farming.

In 1885, wheat farming had still to reach its statistical peak in Central California. But the proliferation of irrigation projects, developments in horticulture and viticulture, and the completion of additional rail lines were bringing about a change to more of an orchard economy.

Still, in 1886, Tulare County would produce nearly six million bushels of wheat, roughly one-third of the state’s entire production. And, in 1888, Traver would ship more wheat than any town in the world ever had. It wasn’t until 1891 that the Traver Advocate would proclaim that “the reign of King Wheat is nearly over; the orchard, vineyard, apiary and poultry farm is usurping his domain.”

LAND MONOPOLIZATION

Monopolization of the land by a relative few had made bonanza farming possible. As Charles Keller traveled through the heart of the great Central Valley, he could look out and see many of these vast holdings. In 1871, 516 men in California owned 8,685,439 acres. In Fresno County, there were 48 landowners with holdings of 79,000 acres or more each. Partners Henry Miller and Charles Lux had managed to acquire 450,000 acres by the early 1870s, and that figure would eventually double.

How had so much land come to be acquired by so few in California? In 1871, an insightful pamphlet, Our Land and Land Policy, by San Francisco journalist Henry George, traced the problem back to the Mexican land grants. With them, George lamented, began California’s history of “greed, perjury, of corruption, of spoliation and high-handed robbery, for which it will be difficult to find a parallel.” Strong words, but Carey McWilliams would later call even that a conservative statement.

In his classic work, Factories in the Fields, McWilliams wrote of speculators emerging from “dusty archives with amazing documents,” and explained how men who came to be owners of these grants had acquired them from Mexican settlers “who had sold an empire for little or nothing.” The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had guaranteed property rights to Mexicans in proceedings, rested on these native Californians. With few assets beyond the tenuous title to their land, it is easy to imagine how unscrupulous speculators could acquire what were already questionable claims.

Many times, these holdings became vastly enlarged through liberal and unregulated resurveying. The point, McWilliams emphasized, was not that settlers were swindled and huge profits made, but that the grants, many known to be fraudulent, were not broken up. The monopolistic character of land ownership in California was established.

Keller, himself, had experience attempting to settle on a disputed land grant. In 1869, after his unsuccessful stint as a San Bernardino brewer, he headed to Mission San Buena Ventura, where he learned there was government land to be had.

This land [Keller once wrote] was in dispute, the Mission claiming it as a Spanish grant whereas people took up the land contending that it was government property, that the grant was false and counterfeit. The settlers employed a lawyer to contest the claim of the Mission. I remained on that claim two years. We employed this lawyer for $2,000 to fight our case and later found that he had taken our retainer and then got $5,000 from our opponents. Of course, the case was dropped; we lost and we ejected.

Keller continued his northward migration, this time into Sonoma County, where he met Caroline Woodard, a teacher at the district school. The two were married in Healdsburg in 1871, where they remained for two years. They were soon able to buy a cattle ranch near Eureka and operated a dairy business for three years. Then Keller decided to take on a local monopolist. Looking back in a brief autobiographical manuscript, Keller recalled the episode:

I separated my herd, farmed out the milk cows and drove everything that would make beef to Eureka, the county seat. I opened a market in opposition to a millionaire land and cattle owner who had driven out, by underselling and later buying out, everyone who had ever attempted to oppose him. I determined I would stay to see how long he would last. It was scarcely six months before he came and made terms.

Just how accurate Keller’s account of his triumph against the millionaire is hard to say. But we do get a prime example of an attitude that Keller undoubtedly shared with many Californians of the 1870s. After a decade dominated by severe economic depression, the state had been polarized into tight sectors of poverty and wealth. This polarization was caused, according to Henry George, in great part by land monopolization. Charles Keller was one of many who shared that realization, and any business success Keller might realize represented a great victory against the wealth and corrupt barony of California.

RAILROAD LAND AND MUSSEL SLOUGH

Wealthy individuals were not the only entities to control vast areas of land in 19th-century California. The railroads, most notably the Central Pacific, which eventually merged with the Southern Pacific, owned millions of acres by the 1870s. This land had been granted to them by the government in alternate sections along various rights-of-way of proposed rail lines that in addition to cash subsidies provided the capital to build and begin operations of the railroads. As Keller, in 1885, was traveling south by the giant locomotive of progress, belching steam and smoke over twin bands of iron, he had to be aware of the railroad’s role in shaping the state. And thanks to one particularly painful episode, still a fresh wound in the minds of most residents, Keller’s awareness and opinion of the Southern Pacific Railroad’s contributions would have been decidedly one-sided.

Frustrated farmers, merchants, and land seekers had long blamed their troubles — high transportation rates, a slumping economy, and frustratingly slow agricultural development — on the highly visible railroad monopoly. In the Mussel Slough area, near Hanford in the west of what was then still Tulare County (now Kings County), groups of settlers began moving onto railroad-reserved sections of land in the early 1870s. The reserved land had yet to be patented to the railroads, and much as Keller had done on the Mission claim in Buena Ventura, these settlers were betting the claims would be voided by the courts.

The settlers tried in vain to file claims on the land. They sent petitions to Congress with no result. In 1878, some Mussel Slough farmers formed the Settlers’ Grand League to publicize their position and create solidarity. Seeking to allay growing alarm, the railroad sent out prospectuses, which assured that when the railroad won title, the farmers occupying the land would be offered the right to purchase land at $2.50 per acre “without regard to improvements.”

The railroad received legal title to their grants and began to send land appraisers to evaluate their holdings as a step toward sale. The land was first offered, as promised, to those in possession, but at exorbitant prices of $17 to $40 and even $80 per acre, a value that reflected the improvements made by the settlers. League members refused to pay. The courts, in 1879, upheld the railroad’s right to evict the settlers, who were by this time squatters in the eyes of the law.

The situation deteriorated. In May 1880, U.S. Marshall Alonzo Poole, along with a Southern Pacific land grader and two recent purchasers of railroad land, set out to take possession. While settlers had congregated in Hanford for a picnic, unaware of Poole’s mission, two ranches had the furniture removed. After emptying the second ranch house, Poole and his men were met by a contingent of settlers on horseback, who “arrested” Marshall Poole and demanded that the other men surrender their guns. Suddenly a horse reared, knocking Poole into the road. Shooting broke out and five of the settlers and one of Poole’s men were killed. Another man from the Marshall’s party was later found dead in a field with a gunshot in his back.

The tragedy at Mussel Slough was an immediate cause celebre. Settlers, frustrated at their inability to acquire land, cast the railroad as pure villain. Nearly 20 years later, Frank Norris summed up their attitude in his historical novel, The Octopus. In the fictional account loosely based on the Mussel Slough affair, he called the railroad:

…the symbol of a vast power, huge, terrible, flinging the echo of its thunder over all the reaches of the valley, leaving blood and destruction in its path; the leviathan, with tentacles and steel clutching into the soil, the soulless Force, the iron-hearted Power, the Monster, the Colossus, the Octopus.

EXPOSING DUMMY FILERS

Large corporations, such as the railroad, were easy targets for the disgruntled poor. Their ability to exploit land laws and swindle the government out of countless acres of land was a major cause of the widening gap between poverty and wealth. Charles Keller became well acquainted with just that sort of swindle.

After his triumph against the millionaire competitor in the meat business in Eureka, Keller apparently enjoyed several years as a successful merchant. It was while running that market that he “became acquainted with the fraudulent entries that were being made in government land in Humboldt and Trinity Counties.” He described learning of a scheme by lumber companies of using dummy buyers to file claims on government land:

This news was brought to me by various people coming into the meat market, and the stealing was so gross and such a breach of the government intent to throw these lands open that I induced various of my informants to make affidavits. I forwarded their statements to the Land Office in Washington. Each affidavit stated that the best of the timber lands were being located on by these dummies and were to be transferred later at the request of the companies who hired the locators. Each of these [dummy filers] received fifty dollars when proving-up time came and they turned the land over to the milling companies.Keller and California Land

Several of the parties were arrested and I was cited to appear as witness. However, the money influence of those for whom the land was being taken was such that neither of the head men was arrested, but a few of the poor dupes whom they had subverted to do their work were sent to prison. After that my time in Eureka was nearing its end because everyone was so hostile to my movement. Then having a chance to dispose of my business, I sold out.

Again, Charles Keller found himself on the move, this time ending up back in San Francisco where he saw an advertisement for business opportunities in the brand-new town of Traver. He quickly jumped at the chance, and it was on a train trip between San Francisco and his new home in the Central Valley that another golden opportunity came his way.

OVERHEARD OPPORTUNITY

Keller had learned a valuable lesson from his whistleblowing in Eureka, beyond the obvious one about angering powerful men in the town where one does business. He had become “conversant with the essentials necessary to secure” government land as set forth by the Timber and Stone Act of 1878. Designed to provide for the sale of 160-acre tracts of surveyed land, the value of which was chiefly in the timber and stone upon it. Such land could be purchased for $2.50 per acre. But, as Keller had also learned in Humboldt, this lent itself to fraud. The Timber and Stone Act was not the first land legislation to avail itself of widespread fraud in California. The Swamp and Overflow Act of 1850 was designed to provide the state with money for reclamation of land deemed more than a certain percentage swamp or overflow, which the state offered for $1.25 per acre. But as this process depended upon locating and determining swamp land, government surveyors found themselves in an easily corruptible position. Some very valuable land was returned to the State of California as swamp and quickly bought up at the bargain price by well-connected and influential men.

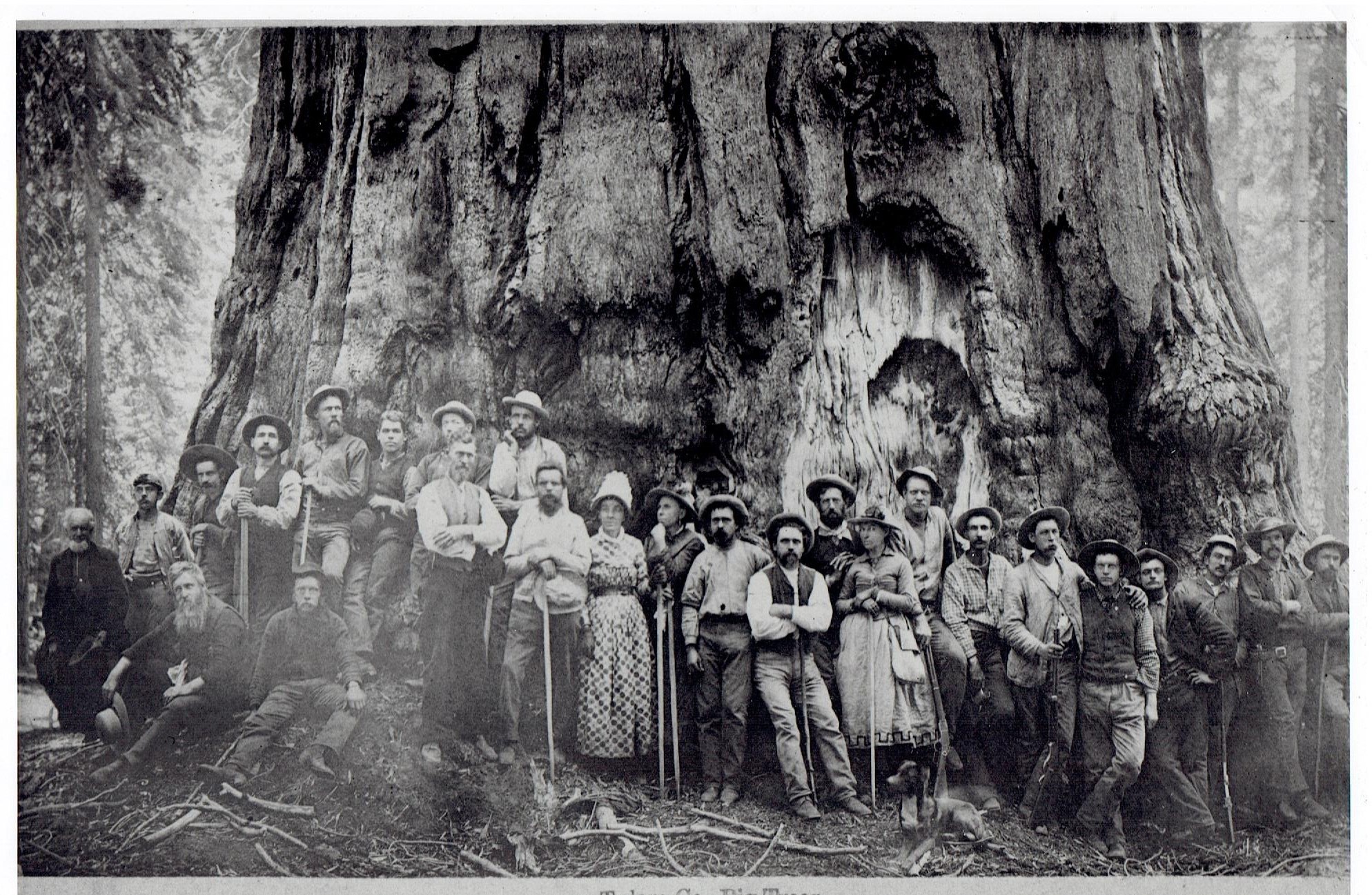

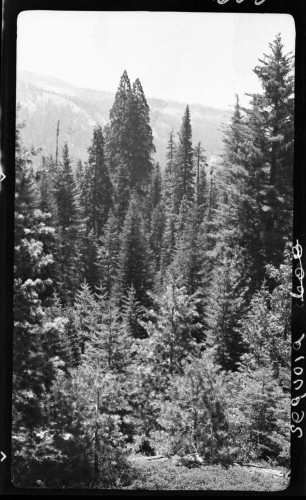

One example of such abuse lay just to the east of Traver in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of Tulare County. In 1883 and 1884, W.H. Norway and P.M. Norboe surveyed the area in and around Giant Forest, where some of the most impressive groves of giant sequoias in the world were located. They returned to the state the meadows, which during spring did contain a fair portion of swamped land, along with the dry forest land, deeming it all swamp and overflow. Norway reportedly wrote up his field notes in camp without doing any actual surveying, and for a consideration of 25 cents per acre would declare any land as swamp or overflow. In this way, the land became state property and then passed into private hands, allowing the lush meadows of Giant Forest to become summer pasture for Tulare County stockmen.

One of these surveyors, P.M. Norboe, happened to be on the same train with Charles Keller in the spring of 1885. Also on the train that day was P.Y. Baker, the civil engineer behind the 76 Land & Water Company. Keller’s own accounts of their encounter are somewhat contradictory, but in one version Keller claims to have overheard a conversation between Baker and Norboe, wherein “Baker informed his companion that east of Visalia was the most magnificent Forest of giant redwoods… opened for sale by order of the Interior Department.” The element of serendipitous eavesdropping was probably played up by Keller for dramatic effect. In another account, he admits he simply “introduced myself and asked if I might take part in their conversation,” and then learned of the “virgin forest of giant redwoods, practically within sight of Visalia, wholly unknown to the average citizen” that belonged to the government and was “actually open to purchase as timber land.”

What would this knowledge mean to Charles Keller, a merchant who now owned a market in the thriving valley town of Traver? His future certainly seemed promising without speculating on timber land in the mountains. Keller’s only experience with lumbermen involved being run out of town by them in Eureka. But Keller was interested in this discovery of available timber land, not just for himself, but for a far greater purpose.

Keller belonged, at that time, to the Co-Operative Land Purchase and Colonization Association of San Francisco. The association was an outgrowth of various labor and social reform organizations, most significantly the International Workingmen’s Association, to which Keller also belonged. It is likely Keller had even attended a meeting of this association during this last visit to the Bay Area — meetings at which the membership was reminded of its primary duty, which according to Keller was “for each to consider himself a committee of one to seek out opportunities to purchase” land with resources sufficient to sustain a cooperative colony.

It was almost as if this opportunity had sought out Charles Keller. As the train pulled into the Traver depot, still under construction, Keller couldn’t wait to further investigate his findings and inform his associates in San Francisco. He became increasingly excited about the prospects for the future. It was now a future he envisioned set in the lush forests of the mighty Sierra Nevada.

SOURCES: The Charles F. Keller papers, housed in the Sequoia National Park historical archives, was a valuable source for this chapter. Some of the books consulted for the chapter include: Land in California: The Story of Mission Lands, Ranchos, Squattters… by W.W. Robinson (UC Press, Berkeley, CA 1948); Empire Out of the Tules, by Brooks D. Gist (Tulare, CA 1976); Railroad Crossing: Californian and the Railroad, 1850-1910, by William Deverell (UC Press, Berkeley, CA 1994); Factories in the Field, by Carey McWilliams (1939); and Frank Norris’ novel The Octopus (Signet Books, 1964, originally published in 1901). Douglas Hillman Strong’s unpublished dissertation “History of Sequoia National Park,” was also valuable, as was Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed’s Challenge of the Big Trees (SNHA, Three Rivers, CA 1990) and The Sierra Nevada, A Sierra Club Naturalists’ Guide (San Francisco, 1979) by Stephen Whitney.