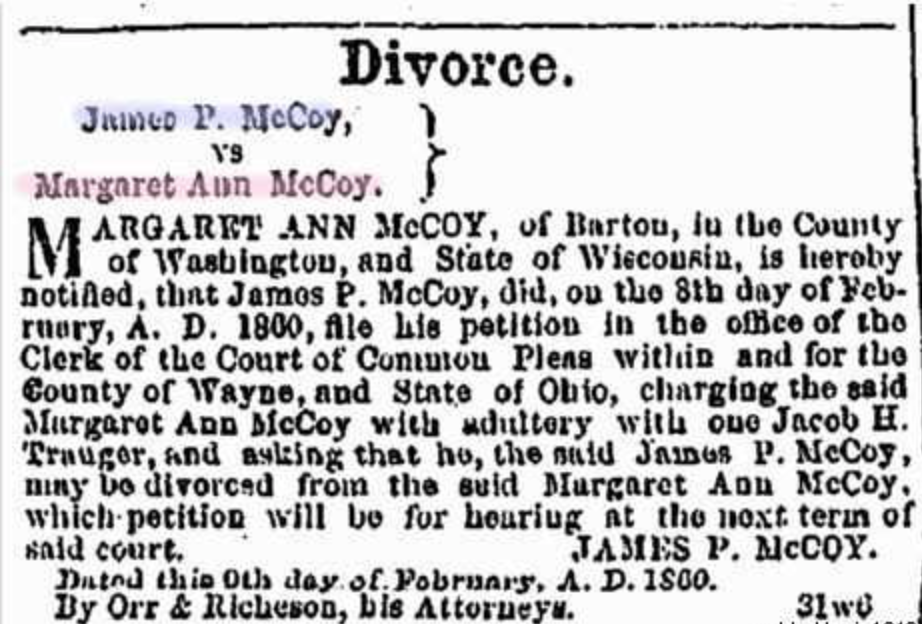

This the third installment of a four-part series that explores a small portion of the embellished lore associated with the creation of Sequoia National Park, exposing little-known aspects perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. In previous segments, we met Will Trauger who was tumbling down a mineshaft (Part 1), the legend that’s James Wolverton, and a group of Three Rivers Boy Scouts searching for Wolverton’s grave (Part 2). In this third part of the series, we meet Joel Rivers Woolverton at his ghastly end.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 14 October 2019, 3RNews

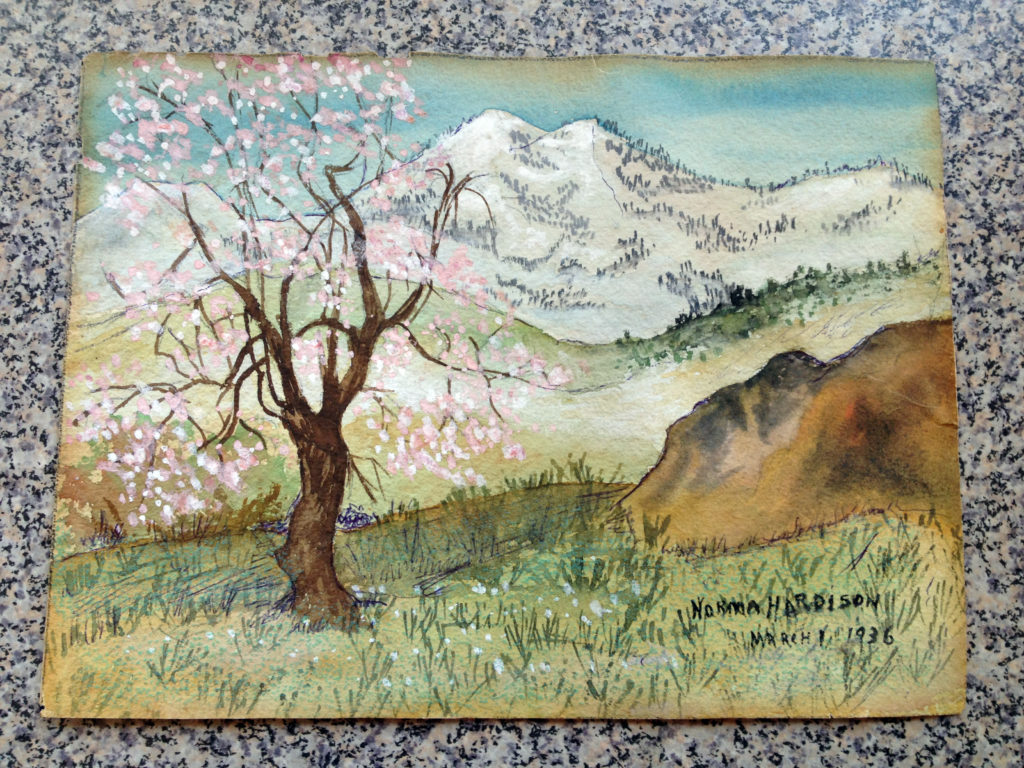

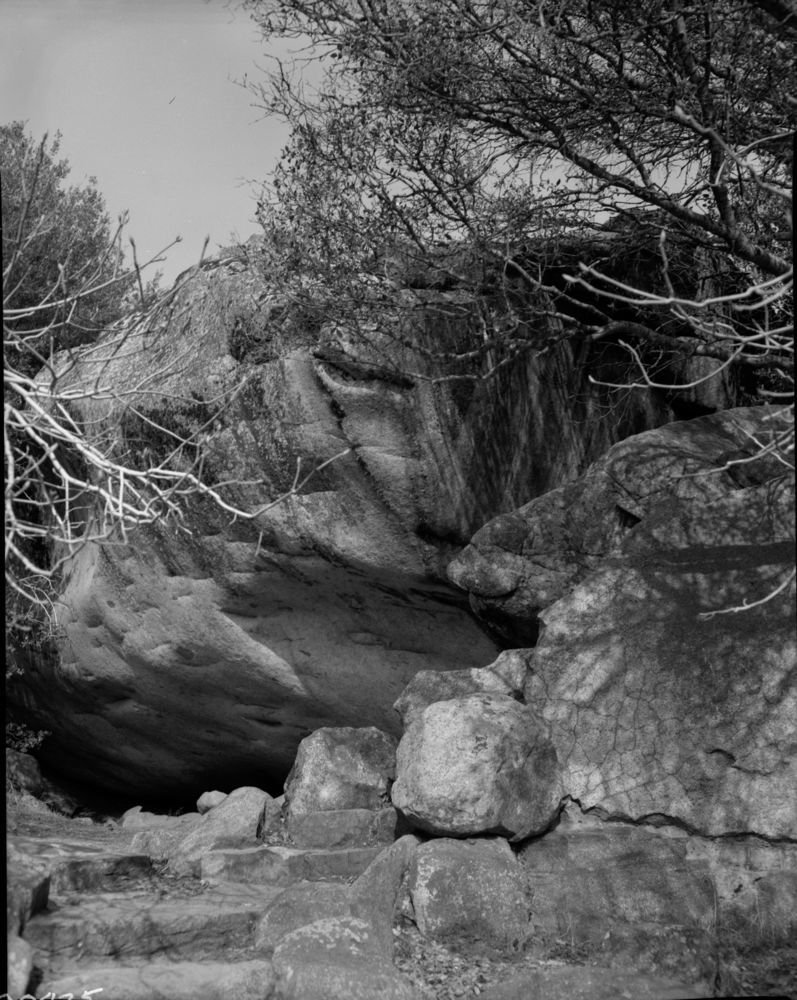

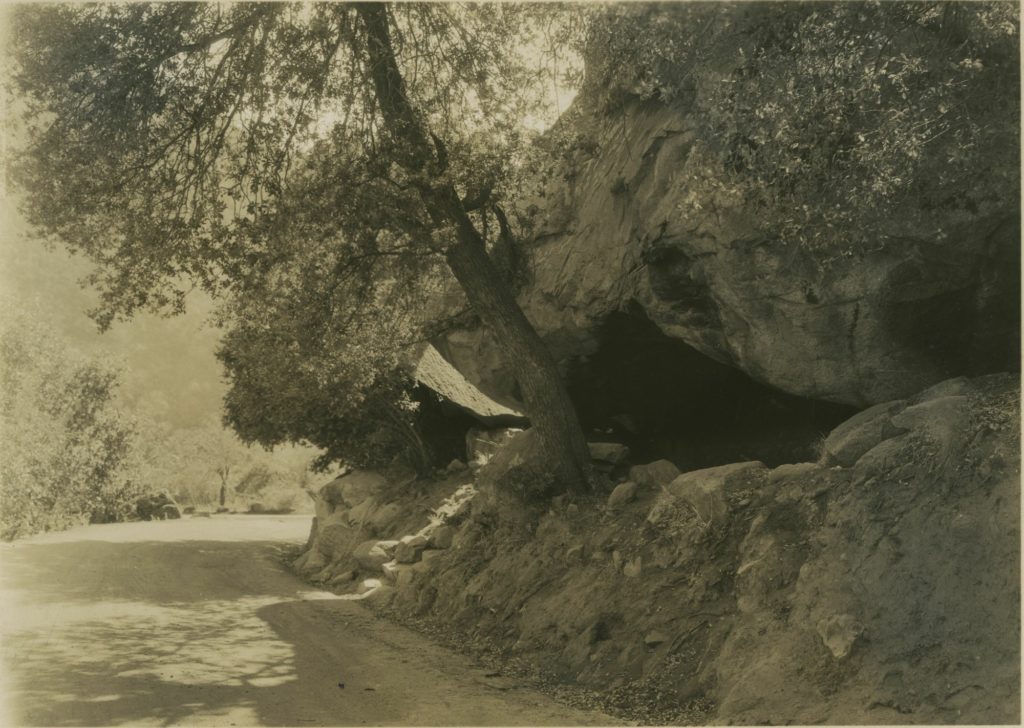

Before we return to Will Trauger at the bottom of a forty-foot mine shaft, let’s step back to a time when Will owned the property where Three Rivers Boy Scouts were to seek James Wolverton’s gravesite in 1936. It’s the last week in March 1893, and Joel Rivers Woolverton is lying helpless on the ground at Hospital Rock, about five miles northeast of Will’s place.

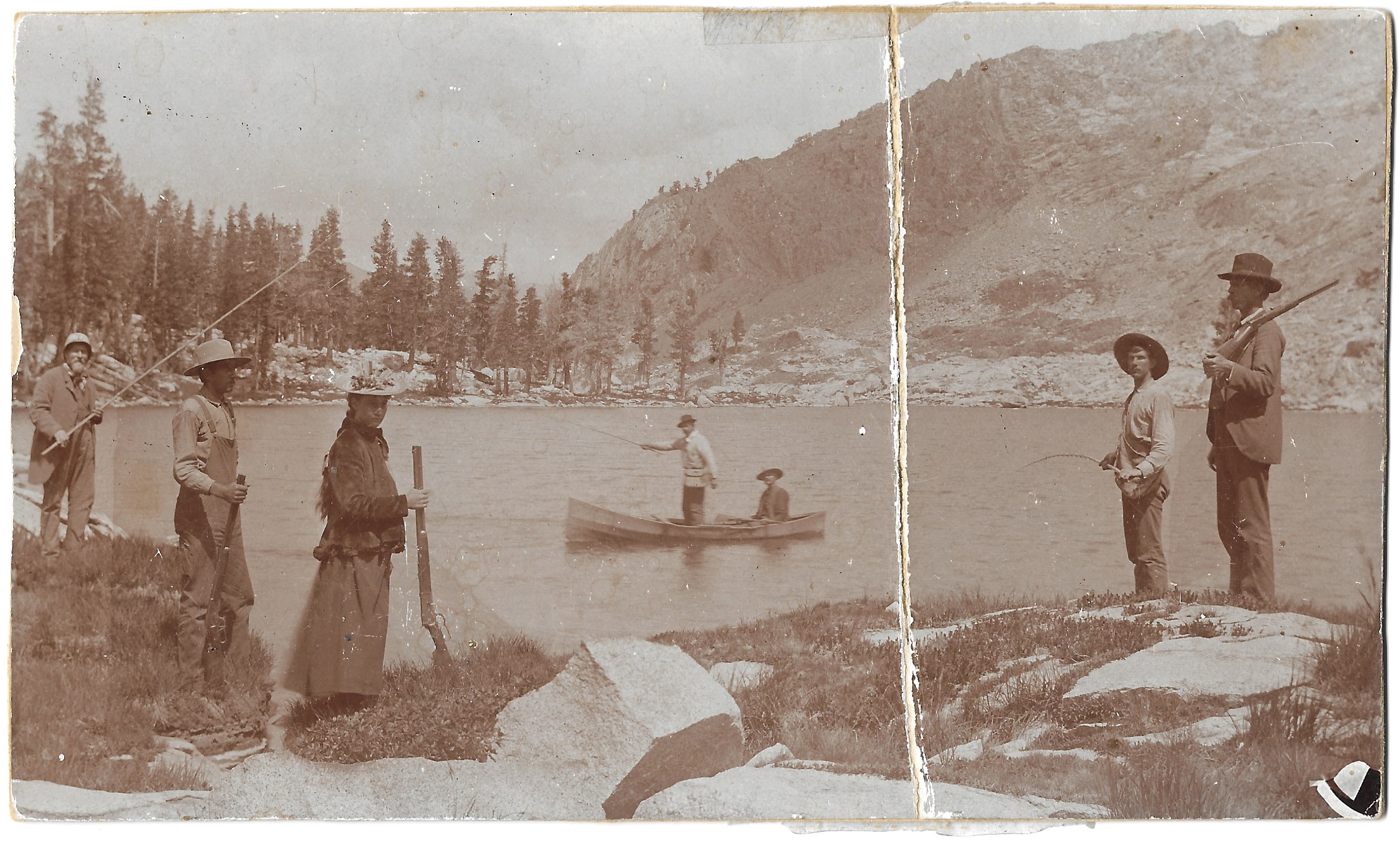

Joel wasn’t the first Euro-American to lie there, according to Walter Fry, the first civilian superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. In 1860, John Swanson and Hale Tharp, who claimed to be the first Euro-American in the area, were exploring when Swanson injured his leg. They sheltered under Hospital Rock for three days while the Potwisha Monache tended Swanson’s wounds with a poultice of jimsonweed leaves and bear fat.

Joel also wasn’t the first to suffer there alone. In 1873, a hunter and trapper named Alfred Everton was shot in the thigh by one of his own guns. He had stretched a string across a bear trail and attached the string to the gun’s trigger. He meant to shoot a bear with it, but accidentally brushed the line himself. His hunting partner carried him to Hospital Rock where Everton waited alone until his partner returned with help three days later.

Now Joel was there, alone, immobile, dying of an illness that prominently featured an abscessed groin. In other words, it is quite possible he was suffering the final stages of a sexually transmitted disease.

How did he end up at this point?

Joel was born in about 1832 in the farming country of Ossian, New York. His father, Joel Woolverton III, had started producing children at the age of fifteen. Not all survived, but when our Joel was born seventeen years later, he had at least five older siblings at home.

His parents didn’t stop with Joel. By 1840, he had four more siblings, with a fifth on the way.

Perhaps weary of farming, disgruntled with a crowded home, or simply yearning for wealth and adventure, Joel left New York by 1850 to join his older brother Alva and assumed brother Chancy in Ohio. From there, Joel and Chancy traveled overland to the California gold fields. They were mining somewhere in Placer County, California, when they registered to vote in the 1852 presidential election.

Four years later, Chancy was back in Ohio. Joel, however, kept following his dreams of wealth from gold camp to gold camp.

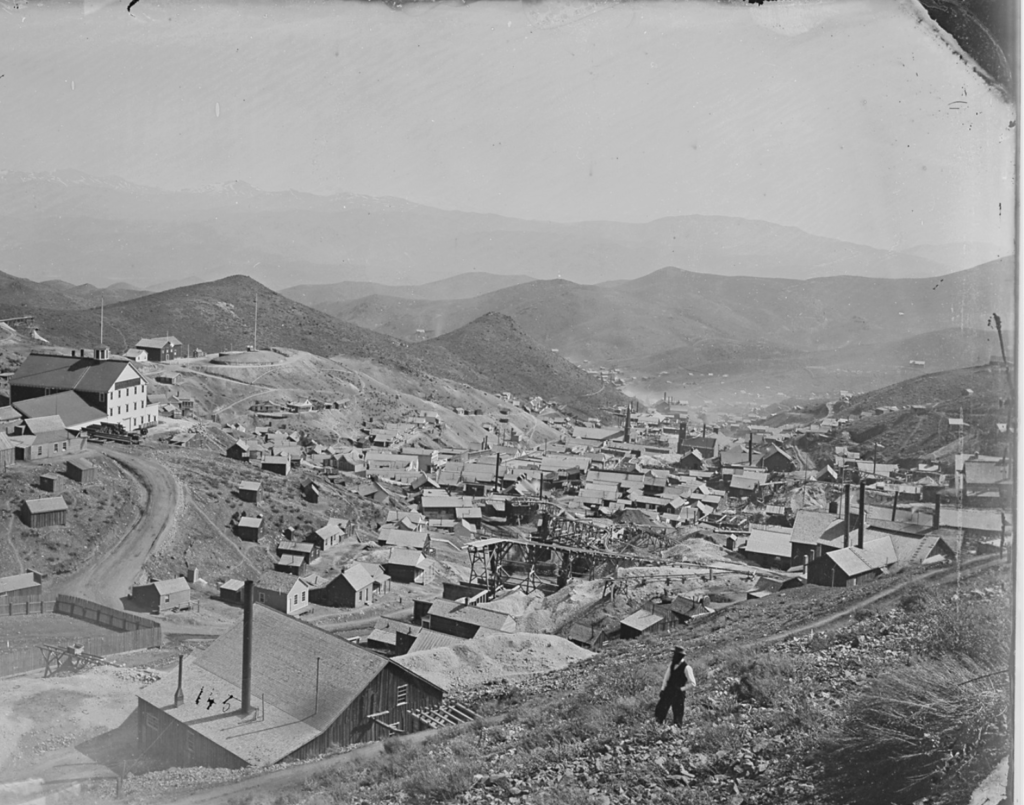

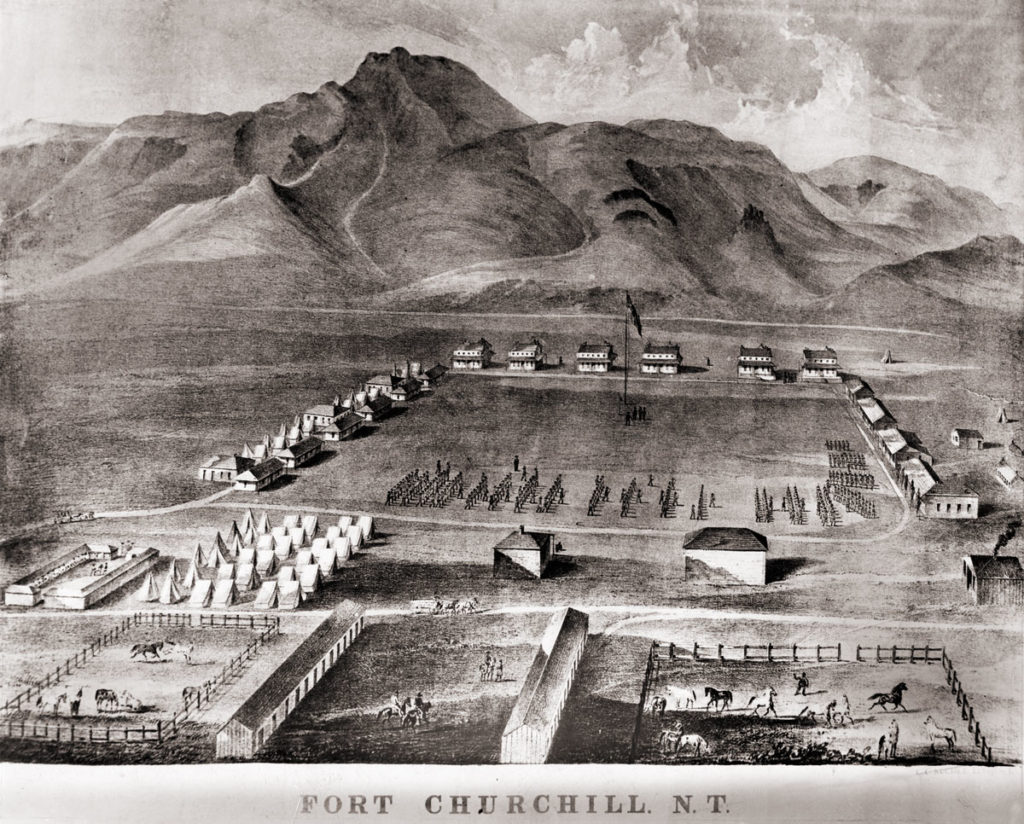

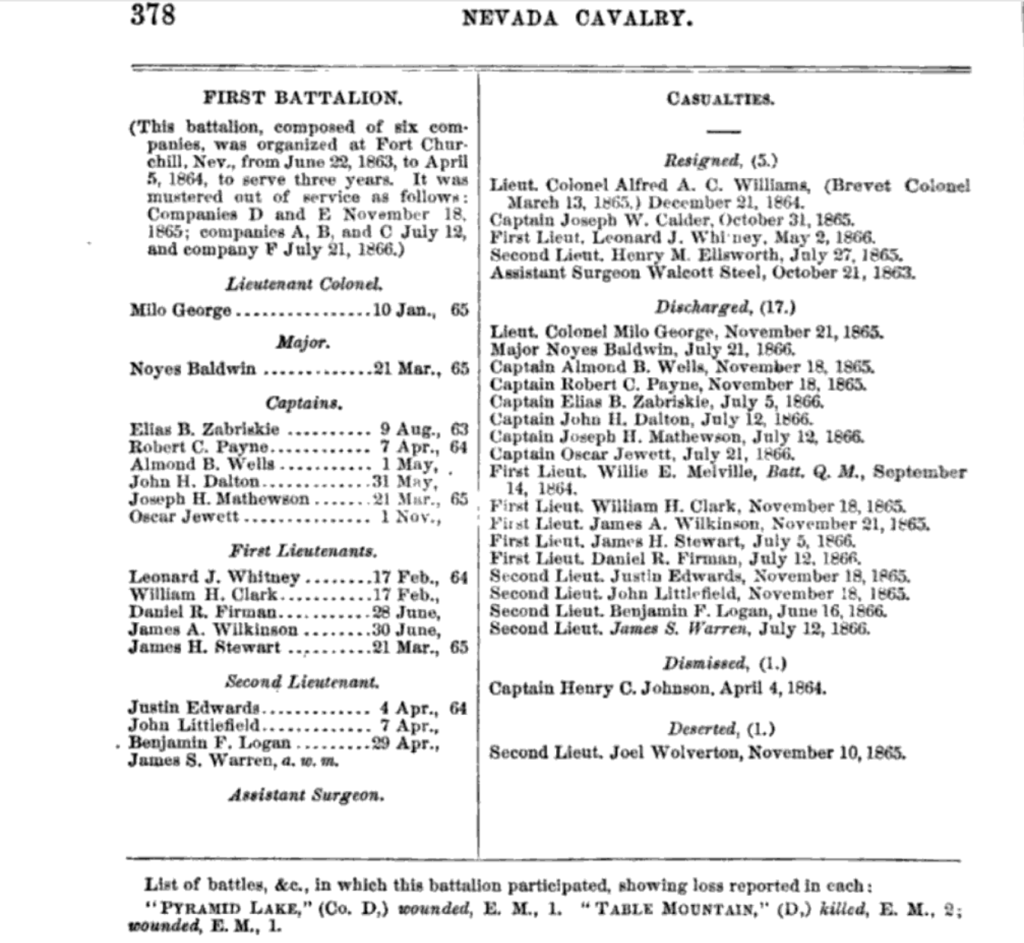

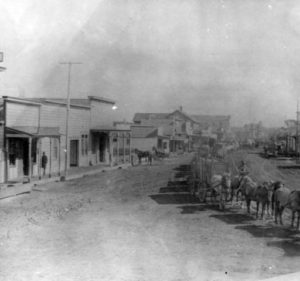

The Civil War found Joel in Gold Hill, Nevada, a district that hosted numerous brothels and saloons. There, Joel joined the Nevada 1st Battalion Cavalry, Company D, on September 3, 1863.

His battalion was formed not to fight the Confederate forces, but to control the remnants of the Southern Paiute tribes in the Nevada Territory. Joel had fair skin, light blond hair, and steel blue eyes. At about six feet in height, he towered over most men of his time. He was consistently present at roll call, and quickly moved up the ranks from private to 2nd lieutenant.

He spent the first year at Camp Nye, where he saw no action but impressed his superiors. The next year, he went to Fort Churchill to attend a court martial and then went to San Francisco to be mustered as a 2nd lieutenant.

After that, he and his company went on some scouting expeditions, but did not detect any hostiles. He was acting post adjutant for a short time. His Civil War service was decidedly uneventful, perhaps even boring.

Company D mustered out November 18, 1865. Joel had quit showing up consistently for roll call in September, however, and didn’t show up at all the last week of his service.

As a result, he was the only officer in the 1st Battalion who was declared a deserter. As a deserter, Joel commenced his post-war life without his $50 bounty and land warrant.

After his untimely departure from the Army, Joel seems to have disappeared. He didn’t participate in a census or register to vote, at least not under his given name.

A decade after his desertion, however, Joel resurfaced in the Hueneme District of Ventura County. Named after the Chumash word for “resting place,” the Hueneme District produced an abundance of lima beans and sugar beets. Here, in 1875, Joel registered to vote as a farmer. He had returned to his agricultural roots.

It is uncertain how long Joel resided in Ventura County. A street named Wolverton suggests he may have stayed long enough to make a mark on the land.

Meanwhile, the Nevada government seems to have reconsidered Joel’s record, and officials began to search for him as early as 1869. In 1886, they succeeded in finding him. A certification of service was filed, and on December 8 Joel finally received his $50 bounty.

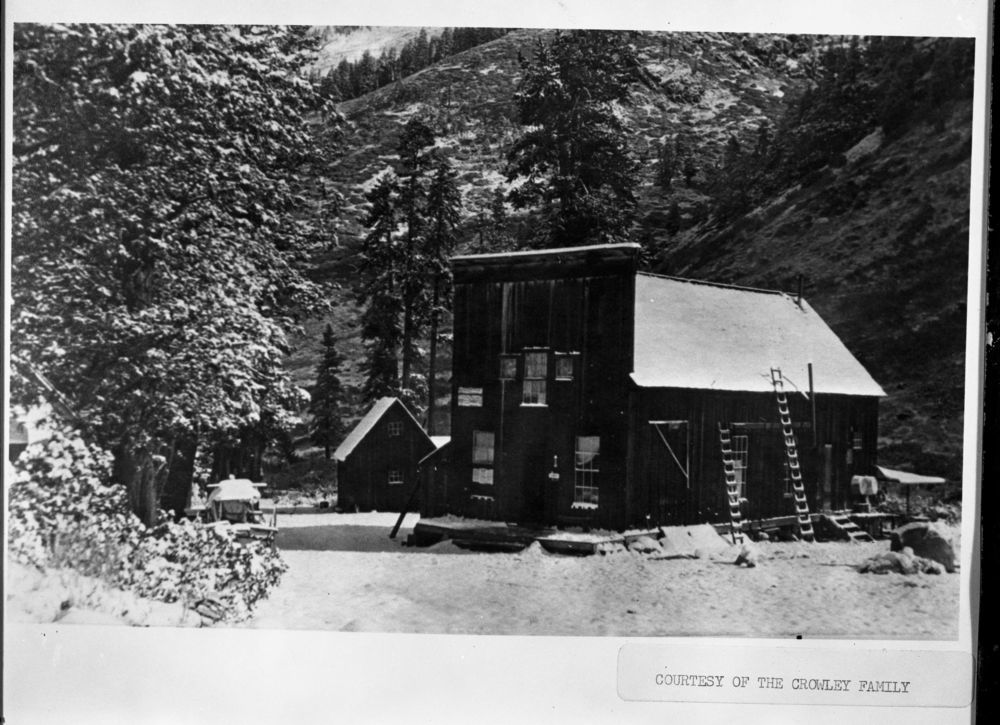

On October 11, 1890, Joel registered to vote in Tulare County as a landless laborer. He was residing in the Kaweah District and may have already taken up residence at Hospital Rock or one of the other abodes that were associated with his name, including Tharp’s Log, Wolverton’s Lean-To, and a cabin in Wolverton Meadow, which was owned by his employer Hale Tharp.

Joel had been troubled by an abscess for some time when he collapsed at Hospital Rock. He could have been lying unable to move for days before Hale Tharp began to miss him.

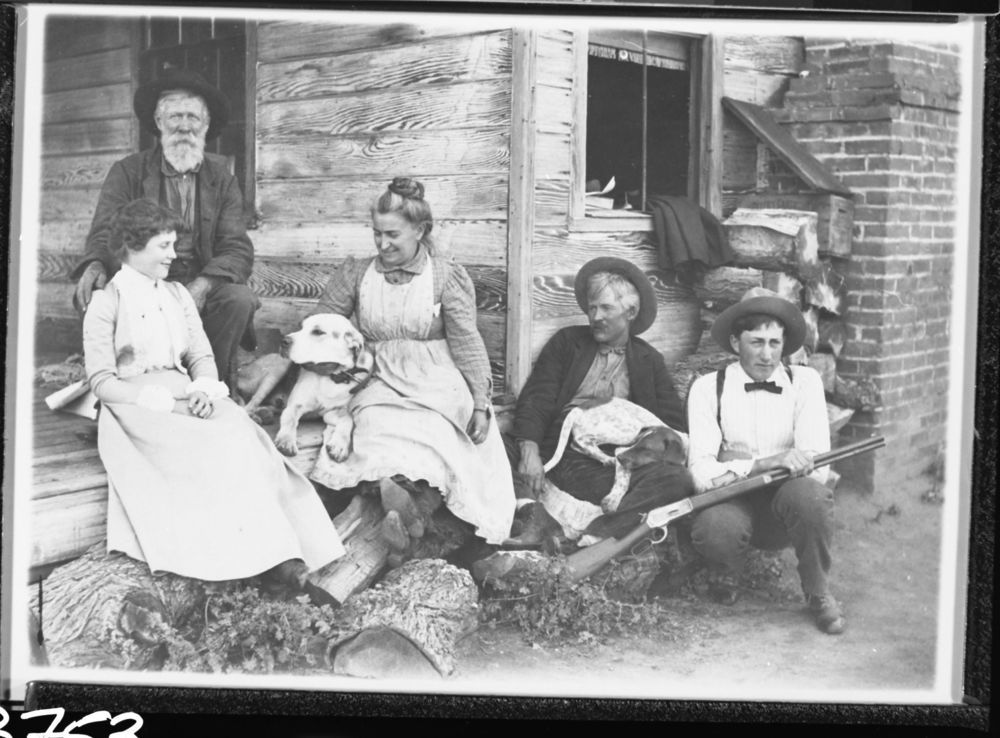

When Tharp found him, it was clear that Joel’s condition was more than he could handle. Tharp went to the nearby homesteads and recruited Will Trauger and two other men to carry Joel 25 miles downriver to his homestead along Horse Creek (present-day Lake Kaweah).

The two-day trip was hazardous due to the heavy spring runoff. The men had to cross the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River holding Joel’s litter above their heads so that the rapids wouldn’t carry him away.

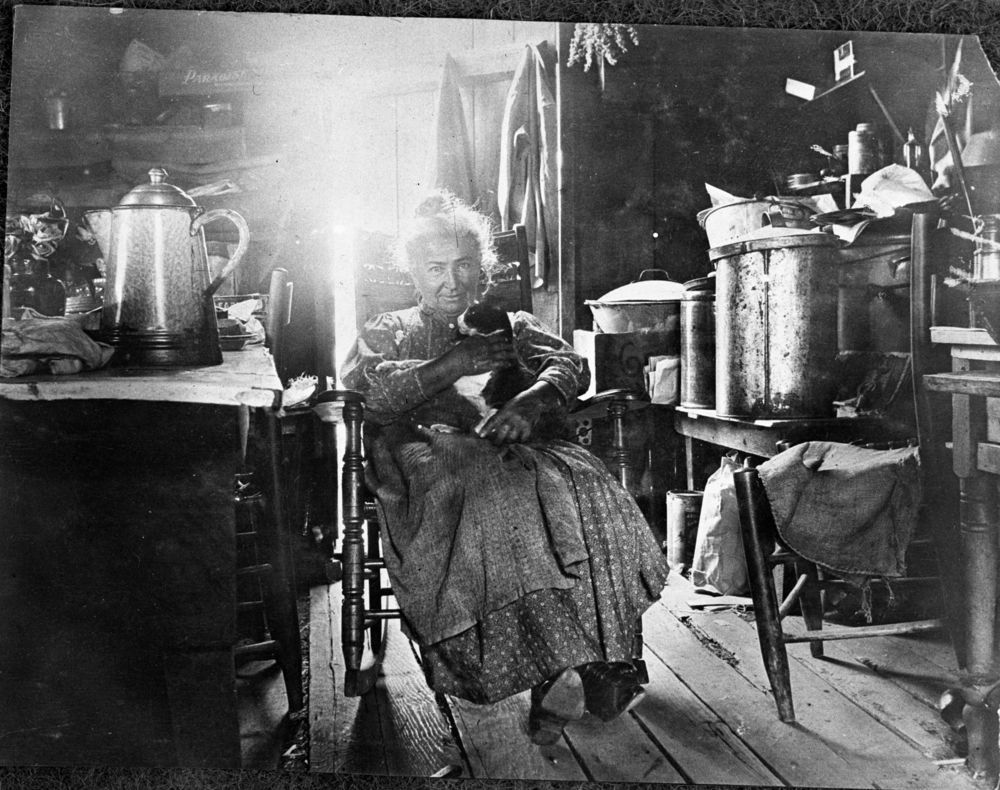

Joel didn’t stay at Tharp’s for long before the men transported him back upriver to Will Trauger’s home, where Will’s adoptive mother Mary Trauger was willing to tend him. Assuming Joel was suffering the final stages of syphilis, he would have had oozing abscesses, dementia, and paralysis. It would have been unpleasant to tend him. Mary had earned her reputation as the “Angel of Mineral King,” however. Additionally, the Tulare County Board of Supervisors voted to pay her an allowance for the six months that Joel remained alive.

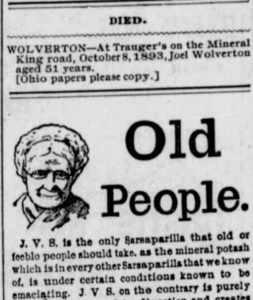

Joel died on October 8, 1893. His 61-year life differed substantively from the legend. His name was Joel, not James. Rather than serving under General Sherman, he was a deserter from the 1st Nevada Cavalry.

He was not in Tulare County from 1874 until his death, and there is no evidence that he owned any land in the county. He was a miner and farmer not a cowboy, fur trapper, and naturalist.

He lived his final months in Will Trauger’s house rather than Harry and Mary Trauger’s Last Chance Ranch fourteen miles farther up the Mineral King Road. And, finally, there is no evidence that he named the General Sherman Tree. Indeed, the name was not associated with the tree until 1897.

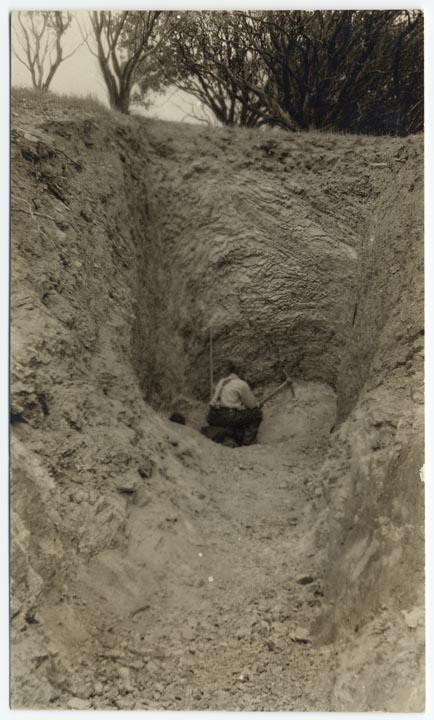

Joel was buried on Will Trauger’s land, however, as that was where he died. Will’s home was about a mile from the confluence of the East and Main forks of the Kaweah River near where the 1879 Mineral King Road crossed the river on a wooden bridge. Will was almost certainly among those who helped lay Joel to rest under the graying grasses, shrubs, and oaks. There is no evidence that the 4th Cavalry attended, so we will have to provide the sound of Taps ourselves and imagine Will walking away from the grave to find a whiskey bottle. In ten years he was going to collide with the bottom of a deep mineshaft.

Are you “dying” of curiosity about what happened to Will Trauger after he hit the bottom of the shaft? Read the final installment!

Acknowledgments:

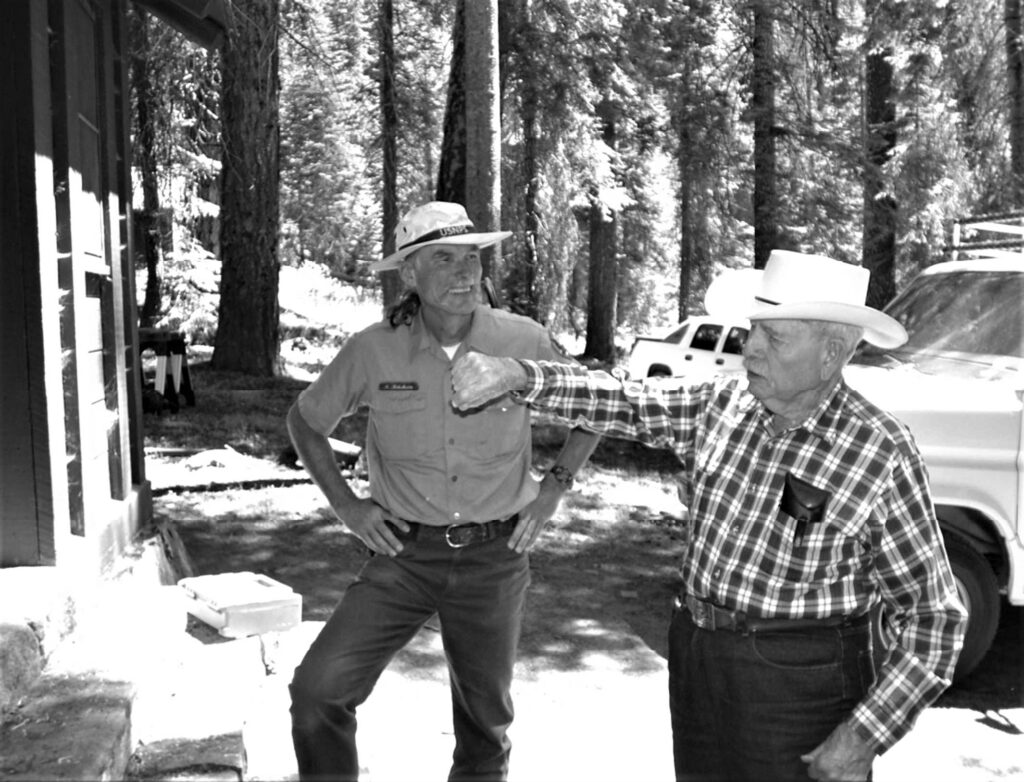

This installment drew on the talents and support of multiple people. I am grateful to Savannah Boiano, research partner, naturalist, and adventurer extraordinaire; Bill Tweed, esteemed naturalist and historian, who has been researching the origin of the General Sherman Tree’s moniker; and the staff and volunteers at the Tulare County Library’s Annie Mitchell Room.