The Road to Sequoia.

This multi-part series was first published in The Kaweah Commonwealth in tribute to African-American History Month, beginning with the February 16, 1996 issue.

By Jay O’Connell, Febuary 1996, Kaweah Commonwealth

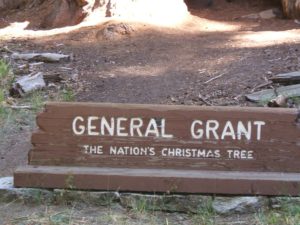

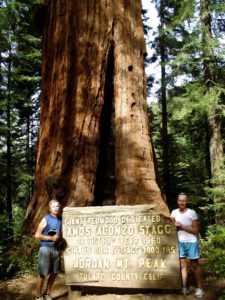

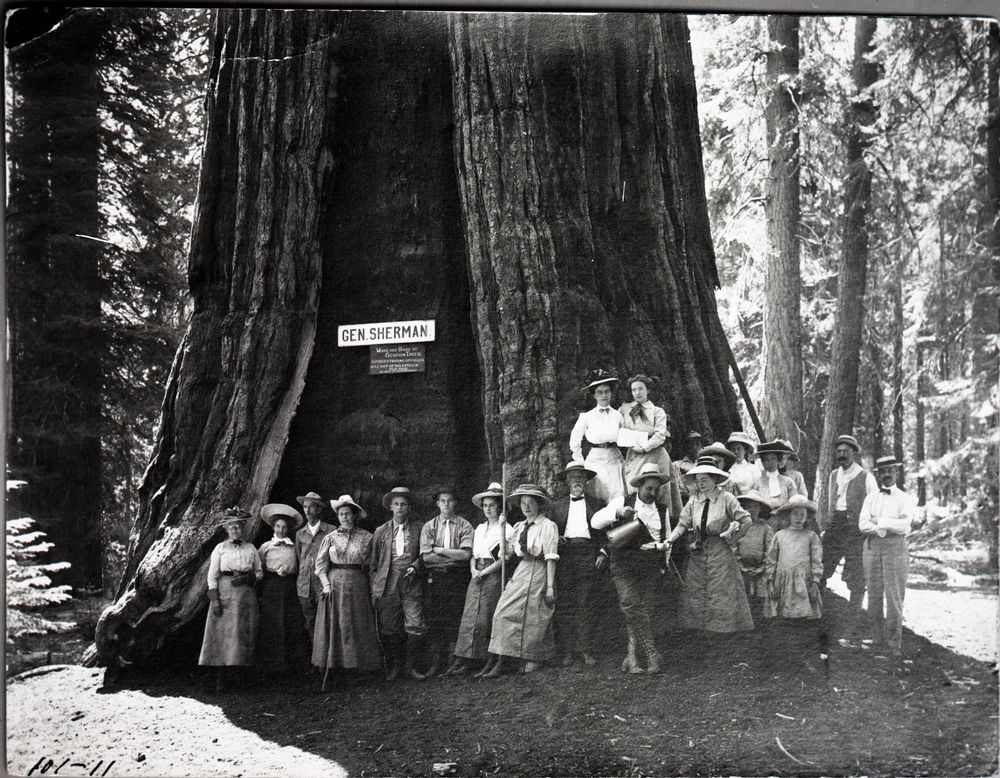

In 1903, Charles Young was military superintendent of Sequoia National Park and General Grant National Park (the predecessor to Kings Canyon National Park), where one of his several major achievements was completing the road the Kaweah Colony had started to Giant Forest.

During his brief time in Kaweah Country, Charles Young had as great an impact on local history as anyone before or since.

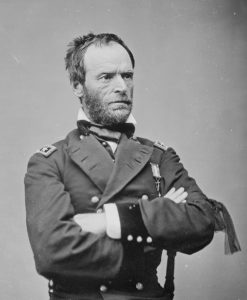

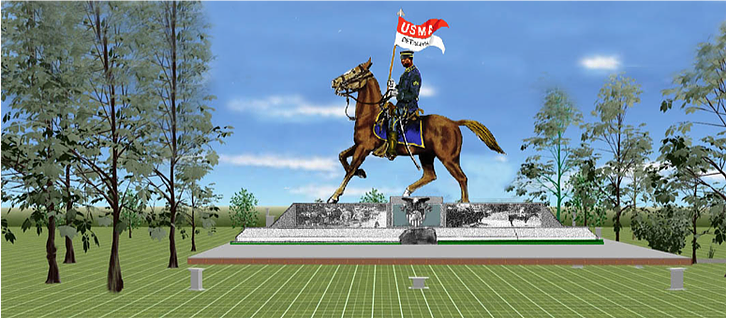

The third African-American ever to graduate from West Point Military Academy, Young faced numerous difficulties due to racial prejudices that, while time has eased, are still prevalent today.

In upcoming installments, we will look at Charles Young and his remarkable military career, examine the impact he had on this area’s history, and share some of the local anecdotes that have been handed down generation to generation about this great American.

PART ONE

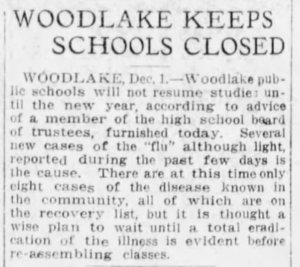

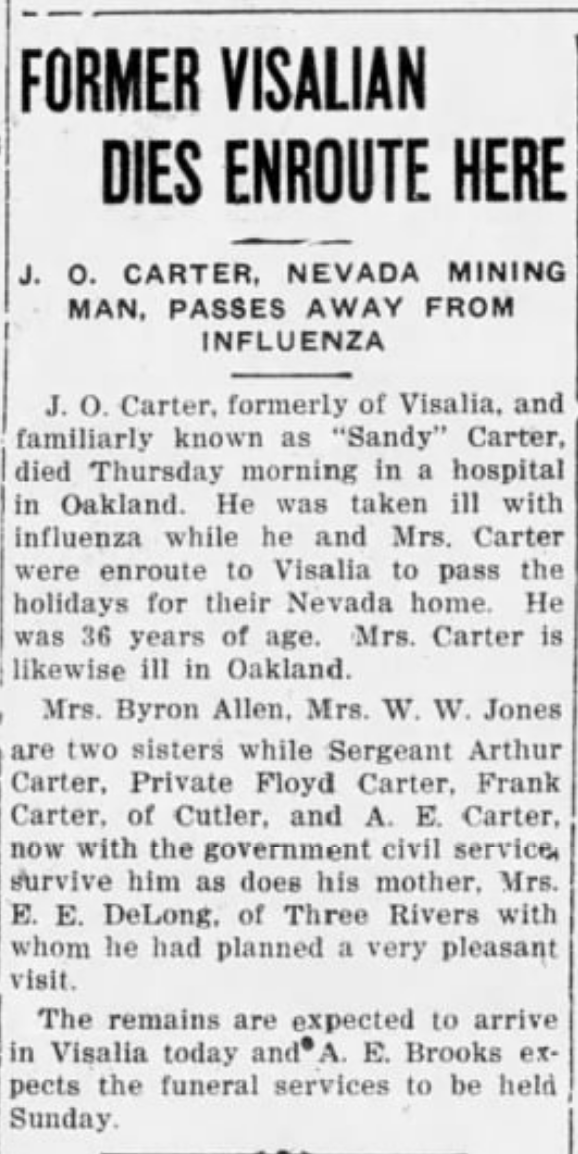

Troops I and M (colored) of the 9th U.S. Cavalry arrived in Visalia this morning en route to the Sequoia National Park. The two troops are under the command of Captain Charles Young… a colored man and the only officer in the United States Army of his color and rank. He is a graduate of West Point and is a man of brilliant parts. His career has been one of hard struggle against prejudice of race. He has, however, risen above all these difficulties by force of character and inherent ability. —Tulare County Times, June 4, 1903

Charles Young was born in Mayslick, Kentucky, on March 12, 1864, to Gabriel and Arminta Young. His parents, both former slaves, moved the family north to Ripley, Ohio, after the Civil War.

Charles graduated from the formerly all-white Ripley High School at 16 years of age. In 1883, having become a teacher there, Young was encouraged by the principal to apply for examinations to West Point.

Earning a high application score, Young was invited to take the preliminary examination. He placed 22nd out of 100 candidates and in June 1884 arrived at the famed military academy.

Things soon proved difficult for the cadet who was accustomed to excelling scholastically. In 1885, he was turned back to the fourth class due to a deficiency in mathematics. When Young graduated from West Point in 1889, he was ranked 49th out of 49.

John Grunigen, Three Rivers pioneer and among the first Sequoia Park rangers, revealed that Charles Young once told him that the worst thing someone could wish on a person was to “make him black and send him to West Point.”

Nonetheless, Young did graduate West Point — only the third African-American to do so — and was commissioned as a second lieutenant.

Later in life, Young admitted to Phil Winser, former Kaweah colonist and local apple rancher, that he “went through hell to get his commission and so had no fear for future life.”

After an initial appointment to the 10th Cavalry and reassignment to the 25th Colored Infantry Regiment, Young finally reported to a preferred assignment with the 9th Cavalry at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in November 1889. According to post records, Young’s time at Fort Robinson was not without blemishes.

His file contains a complaint of “tactical errors” as officer of the guard. A reprimand for neglect of stable duty also mars Young’s record.

In October 1890, Lt. Young’s troop was assigned to Fort Duchesne, Utah. It was there that he was again able to utilize his talent as an educator.

Young served as officer-in-charge and teacher of the post school until March 1894, when he was called upon to fill the shoes of a fellow graduate of West Point. Lt. John Hanks Alexander had been the second African-American to graduate the U.S. military academy, and when he died at just 30 years of age, he was serving as military instructor at Wilberforce University in Ohio.

Young’s career was already tracing Alexander’s, who had graduated West Point two years before Young and also served at Forts Robinson and Duchesne. After Alexander’s death, the head of Wilberforce wrote President Cleveland requesting the appointment of Young to the University. In May 1894, Charles Young assumed duties as Military Instructor at Wilberforce.

In December 1896, the Cleveland Gazette reported that Young had passed the examination for promotion to first lieutenant and “would now be paid $1,800 per year, has a handsomely furnished home free, and is only 32 years old.” The newspaper failed to mention that when Lt. Young was in Leavenworth, Kansas, for the examination proceedings, he could not get accommodations in town due to his race and had to stay in Kansas City.

The Spanish-American War brought further distinction to Charles Young. In May 1989, he was granted a leave of absence from the regular U.S. Army to accept appointment in the 9th Ohio Battalion National Guard as a field officer with rank of major.

According to the Richmond Planet newspaper, this was the first instance “in which a colored officer has commanded a battalion.” Robert Greene’s book, Black Defenders of America, notes that the 9th Battalion was assigned to the 2nd Army Corps at Camp Russell, Virginia, then Camp George G. Mean in Pennsylvania, and finally in Summerville, South Carolina. “Young did not see service in Cuba during the Spanish-American War,” it was stated.

But this claim has been disputed. During the Spanish-American War, he was in command of a segregated squadron of the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers in Cuba.

It has been written that Young charged San Juan Hill (Cuba) alongside Teddy Roosevelt and his famed Rough Riders. Phil Winser of Kaweah, who became good friends with Young in 1903 when he was stationed in Sequoia and corresponded for years afterward with him, wrote in his memoirs that Young was “promoted to a captaincy for conspicuous bravery at San Juan Hill.”

Many Buffalo Soldiers did see service alongside Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, and African-American troops from the 9th and 10th Cavalry later paraded with President Roosevelt.

In 1899, Young rejoined his unit at Fort Duchesne. There he was involved in disputes between Native Americans and local sheepherders and demonstrated a talent for diplomacy.

In 1901, Young was assigned to the recently acquired Philippines. Young commanded troops at Samar and participated in numerous engagements against insurgents. It was during this time that he received his promotion to captain.

On December 27, 1902, the Indianapolis Freeman newspaper reported the following:

The colored officer of the 9th Cavalry, who will in the future be stationed at the Presidio, was a great favorite on the Sheridan coming from Manila to San Francisco and was in great demand. His skin is of the darkest hue of the race, but he is exceedingly clever, a West Point graduate, and a pianist of rare ability.

On May 20, 1903, Captain Charles Young was appointed acting superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. In the days before the National Park Service was created (1916), the management of national parks was the responsibility of the U.S. Army, which had very little Congressional funding for the task.

PART TWO

In 1903, Captain Charles Young, stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco, could already boast of an accomplished military career. He was described in the Visalia Delta as “a man of medium build, very erect, well preserved and though he says he is 39 years old, he looks scarcely 25.”

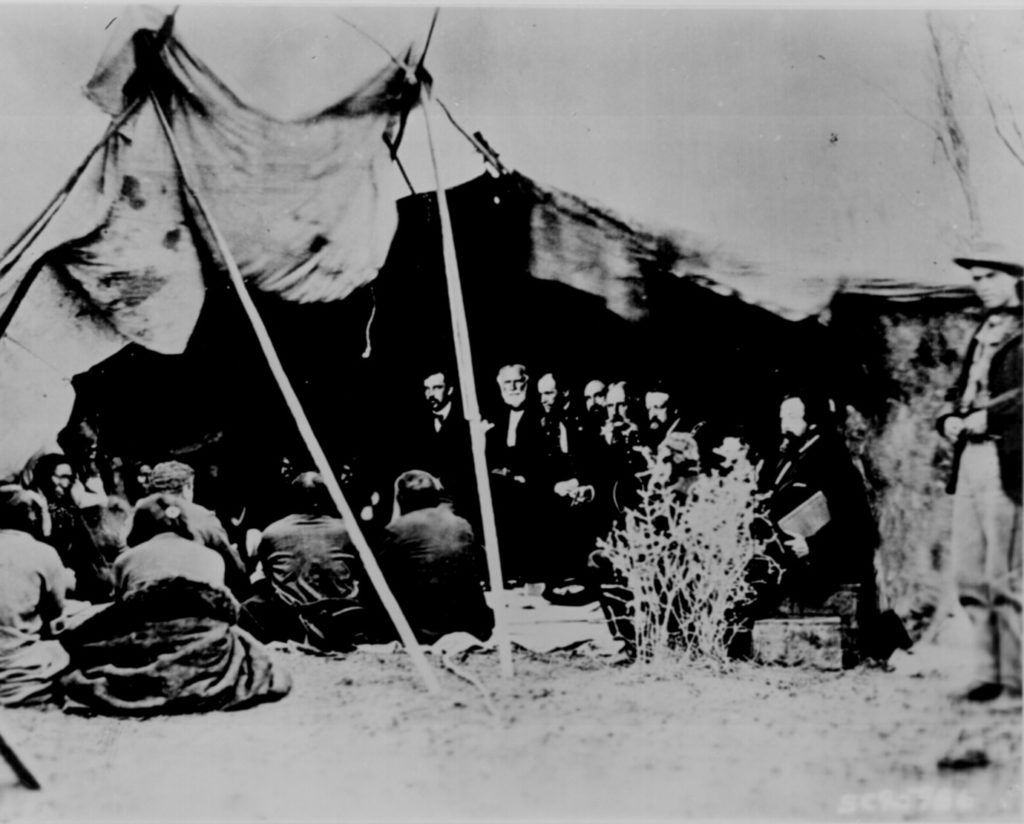

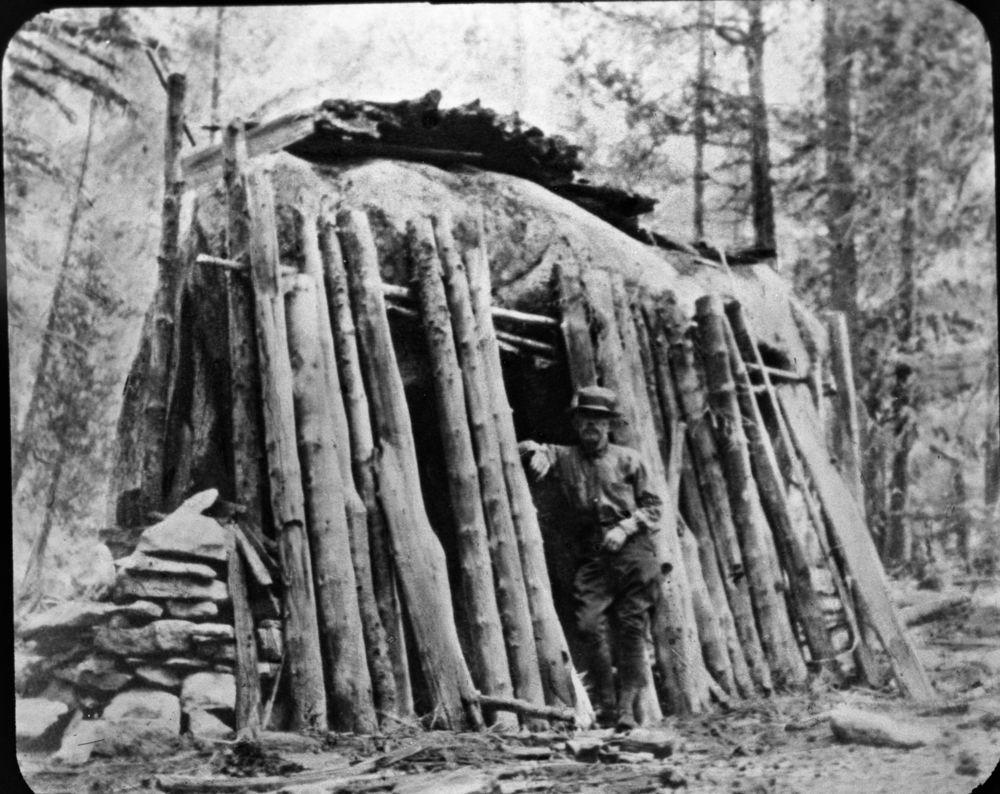

Young received orders to report to Sequoia, and on May 20, 1903, departed San Francisco with Troops I and M, Ninth Cavalry, consisting of three officers and 93 enlisted men. After a 16-day journey, they arrived at Kaweah.

“A general supply camp was established and maintained there throughout the year, as it is centrally located,” Young recalled. “The ground for this camp was kindly offered to the troops by Mr. Ralph Hopping.”

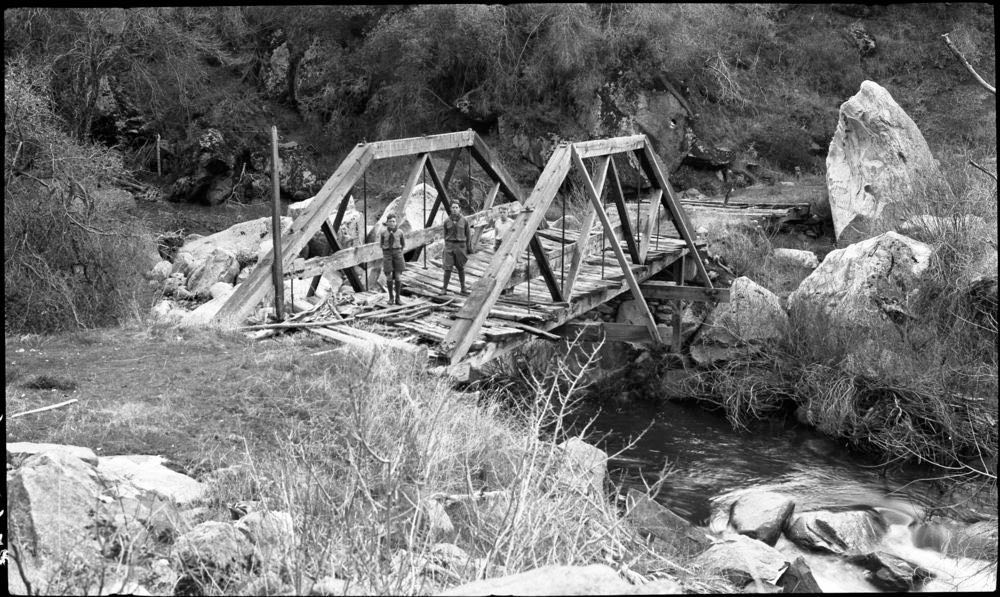

The first order of business was an inspection tour with Ranger Ernest Britten, who had served in Sequoia since 1900. He had already begun repair work on the existing road, which continued the Kaweah Colony road toward Giant Forest (pre-Generals Highway).

The route of extension, still several miles shy of completion, was also viewed with construction engineer George Welch, who had worked on the road for several of the previous summers.

It was imperative they begin road work right away. George Stewart, an original agitator for Sequoia’s establishment, wrote to the Secretary of the Interior on April 14, 1903, explaining that “a large number of people will visit Giant Forest this year, and it is desirable that the road building [commence] at an early date.”

On June 4, Young telegraphed the Secretary, requesting permission to begin work immediately.

“Laborers are on the grounds now,” he explained, and claimed that hundreds of dollars would be saved by beginning work before the ground became hard and dry.

Work commenced June 11, 1903, and on June 20 the Visalia Delta boasted that Captain Young would have the road “smooth enough for automobiles and bicycles.”

The Delta also noted Young’s admiration for his inherited ranger staff, quoting him as saying, “The people who rely upon Ranger Britten to prepare and build trails do not realize his ability to do that work to perfection.”

Ernest Britten also displayed administrative skills appreciated by Captain Young. Writing the Secretary of the Interior, Britten suggested a system of vouchers to guarantee payment to suppliers and asked that money to pay the laborers be entrusted to the officer in charge. Young heartily recommended this request be approved, reasoning that it would greatly facilitate matters, as keeping vendors and workers promptly paid would avoid delays in completing the road.

Most of these men earned two dollars a day as laborers, with foremen earning three dollars per day. George Welch, the civil engineer overseeing the project, earned an impressive $150 per month.

In addition to starting early in the season and keeping men and suppliers promptly paid, one factor was key to the success of the 1903 road-building crew. Captain L.W. Cornish, Young’s eventual replacement, considered it “largely due to the strict personal supervision given by Captain Young, who continually spurred on the men under his employ.”

Young had long before earned a reputation as a strict disciplinarian. His Ninth Ohio Battalion had been considered “one of the best drilled in the volunteer army.”

Captain Young was also a fair and generous leader who knew the importance of rewarding a job well done. Examining National Park Service archives, one finds a letter he wrote to his superior explaining a 10-day absence by Ranger L.L. Davis. Young had insisted Davis take the time off, with pay, after he had supervised the blasting on road construction.

“I ordered him away from duty for rest because of the ill effects of close contact and long use of dynamite,” Young informed Secretary Hitchcock. “If the exigencies of ranger service will not permit him to have those days so richly deserved by him, I shall be glad to refund the money paid him by the department.”

The best example of Young’s rewarding hard work was a well-publicized event in Sequoia National Park’s early history. On September 1, the Visalia Delta offered this report:

The great feast that was given last Sunday at Giant Forest by Captain Young, and the splendid road that has been perfected into the forest are themes of conservation among Visalians who attended…

The elegant feast was put upon the table and some hundred or so guests sat down to honor the completion of the road. The menu consisted of roasted chicken, roast pork, beef, and all the delicious dishes that are served to make them all the more palatable.

Those from this city who sat about the festal board speak in glowing terms of the hospitality of Captain Young and his ability to entertain.

The celebration was the talk of Kaweah Country for a long time. Young had encouraged the workmen by promising this feast upon completion of the road. Everyone who worked on the road, as well as Visalia dignitaries, were invited. The banquet was set out on a huge log and Young, acting as head waiter and assisted by his non-commissioned officers, served the guests from blasting powder boxes attached to shovels.

One account mentions Young’s truly appreciated grand finale. When they were about finished, he announced that this wasn’t all. He had beer — store-bought! — for everyone.

Young was well liked in Three Rivers. He purchased local rancher Marion Griffes’s house during that summer, so it is apparent he was fond of the area and hoped to stay. After completing the road, Young concentrated his efforts on obtaining options for the government to purchase privately owned land in Sequoia. Sequoia National Park seemed to be in Captain Young’s future.

Even Captain Cornish, who technically replaced Young as park superintendent in September due to seniority, stated in his official report, “Owing to the good work performed by Captain Young, Ninth Cavalry, during the present season, I recommend his permanent detail on this duty as long as he is available.”

PART THREE

From the Visalia Delta (October 13, 1903)— In an interview, Captain Young said that he with the other proper officials have seen, or corresponded, with, all of the people who own property within the park lines and have secured their consent as to the sale of the land to the government. As will be remembered, nearly every captain that has been here on duty has made an effort to purchase the private land within the boundaries and convert it into the park.

* * *

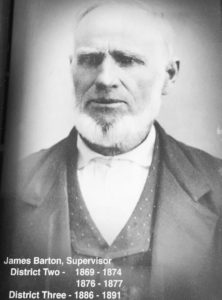

Acquiring options on all the privately held land in Sequoia National Park was an impressive feat. Reading the promissory letters in the Park files, it is apparent that Young received help in obtaining them. Several of the notes are addressed to Ranger Ernest Britten, and in one case, George Stewart acted as liaison.

Unfortunately, Congress failed to act on Young’s recommendation and would not appropriate the necessary monies to buy the land. The problem of dealing with privately owned land within Sequoia would haunt the national park for many years to come.

Still, just obtaining the options was further evidence of Captain Young’s effectiveness as superintendent of Sequoia National Park in 1903. It is testimony to his ability to utilize Britten’s talents and local connections, as well as his own considerable, and somewhat legendary, charms in convincing settlers to sell their land.

That Captain Young charm is best exemplified, perhaps, in the following local anecdote.

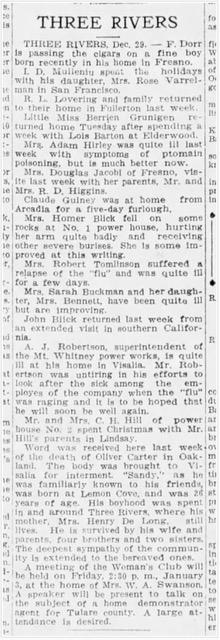

Once, while on patrol near Oriole Lake (8 miles up the present-day Mineral King Road), Young and a number of his Buffalo Soldiers (a complimentary term for the African-American troopers) stopped at the Grunigen’s Lake Canyon house on the Mineral King Road. (The Grunigens were the parents of John Grunigen who had worked on the road for Young.)

It was getting late and Young asked Mrs. Grunigen if she would feed his men. She prepared a meal and invited the soldiers to eat.

Young told her he would have his men file through the kitchen, pick up their plates of food, and take them outside. Mrs. Grunigen informed him that they would do no such thing. They would eat under her roof or not at all.

As Mrs. Grunigen was from Alsace, she was fluent in German and French, but her English was shaky. After dinner, as the soldiers set up camp for the night. Mrs. Grunigen and Captain Young sat out on the front porch and conversed in French until well past midnight.

Young also became good friends with the Winsers. Phil Winser had come from England to join the Kaweah Colony and subsequently started at apple orchard with Fred Savage on the North Fork. Young had once told Winser that he had “come to Kaweah with his heart full of bitterness and left it a different man with a better outlook.”\

In one letter, dated January 6, 1904, Young wrote:

“Oh beautiful valley! You are right, Mr. Winser, when you speak of the charms, due in large measure to the people living there. It will likely be impossible for me to get down now, even though we pull free of the Panama Muddle.”

Despite his desires and others’ recommendations, Young did not return to service at Sequoia. On May 13, 1904, he assumed duties as military attache to Haiti. It was undoubtedly upon learning of this assignment that Young sold Marion Griffes’s Three Rivers house back to him and prepared to relocate to Haiti with his new bride.

Young’s career after Sequoia included several years in Haiti. He later served, at the personal urging of Booker T. Washington, as military attache to Liberie. In September 1915, Major Charles Young was officially assigned to the 10th Cavalry Regiment.

On February 22, 1916, he received the Spingarn Medal for outstanding service in Liberia and, in 1916, Young served in Mexico as part of the Punitive Expedition with General John Pershing. He led a fight against Pancho Villa at Aguas Calientes and his 10th Cavalry came to the rescue of the 13th Cavalry at Santa Cruz de Villegas.

It was written that Major Tompkins of the 13th, upon their rescue, exclaimed, “By God, Young, I could kiss every black face out there.”

In July 1916, Young was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. As Young earned a higher and higher rank, racial prejudice became more of a problem for the Army due to resentment from other officers.

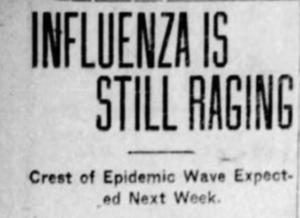

In 1917, Young was ordered before a retirement board. Young had battled malaria in Liberia, and the lingering effects were justification for his retirement.

In 1918, after America had joined the “war to end all wars,” the patriotic Young rode on horseback from his home in Ohio, 500 miles to Washington, D.C., to prove he was still fit for active duty. He was recalled to service and assigned to Camp Grant, Illinois. In 1919, he returned to Liberia as military attache.

Young’s ride to Washington was just one more example of the determination that defined his career. He refused to let the difficulties connected with the racial temperaments of his America get to him. While he could not ignore them, he was able to deal with them in whatever manner most effective.

One example turns up again and again in Charles Young’s life. The episode is reported to have taken place in Virginia, San Francisco, and in Three Rivers.

The local version recounts how Captain Young’s troop was all “Negro except for one white doctor and two white Lieutenants.” Once, at the old Three Rivers Store, the two lieutenants deliberately walked by the Captain without saluting.

Young whipped off his shirt and hung it on a fence post, brought the boys back, and said, “You don’t have to salute me but, by God, you’re going to salute the bars!”

And they did.

On January 8, 1922, Colonel Charles Young, on duty in Lagos, Nigeria, died from an acute exacerbation of an old-standing illness. His body was brought back to the United States, and he was given a hero’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Jay O’Connell was raised in Three Rivers and currently lives in Southern California. He is the author of several acclaimed historical works, including